| Šuppiluliuma I King of the Hittites 1380-1340 BC | |

|

He was the Son of Tudhaliya III.

The following account of Šuppiluliuma’s military exploits is based largely on The Deeds of Šuppiluliuma. The broken nature of this text makes the proper placement of the fragments, and thus the events, difficult to determine. The sequence here follows that presented by Güterbock (1956). Once the Great Syrian campaign begins, the number of sources for Šuppiluliuma’s reign increases and can be used to supplement the fragmentary Deeds. After Šuppiluliuma’s victory against the Arzawans, Šuppiluliuma’s father, Tudhaliya III, no longer appears in the Deeds. The fragmentary nature of the text makes it unclear whether or not Šuppiluliuma immediately became king at this point. It is important to note that the next fragment begins with word of the enemy being brought directly to Šuppiluliuma, who then decided to march against the enemy (rather than ask permission to do so from Tudhaliya, which he had been doing up until then). There doesn’t seem to be any space in the Deeds for the reign of a Hattušili II, which contributes to the difficulties surrounding the question of that king’s existence. The oathes sworn by the sons, officers, and army of Tudhaliya III in favor of Tudhaliya the Younger were not enough to ensure the smooth transfer of kingship in Hatti. With Kaškans still ravaging the land, Arzawa menacing Hatti from the west, and the capital at Hattuša apparently still in ruins, a strong and experienced leader was needed on the throne. A group of officers, including the hitherto immensely successful prince Šuppiluliuma, transgressed their oathes and killed Tudhaliya the Younger. It was a sign of things to come from this royal son, who never seemed to have felt particularly constrained by his word if it interfered with his ambition. During the struggle for the throne, Tudhaliya appears to have been supported by some of his brothers, and these men met the same fate as their sibling. One group of men - who exactly is not known, but they were probably also family members - were banished to the island of Alašiya instead of being killed. This bloodshed in the royal family cleared the way for the accession of Šuppiluliuma as the Great King of Hatti. New Officials: The Great King had the right to make new appointments when he ascended to the throne. In fact, considering the bloody nature of his accession, there were probably plenty of offices available to be filled. We know of the following ones which must have taken place almost immediately: Šuppiluliuma’s brother Zida became Chief of the Royal Bodyguard. Within a couple years Šuppiluliuma’s son Telipinu was appointed Priest of Kizzuwatna (See below) Šuppiluliuma’s Early Campaigns as Great King Šuppiluliuma’s reign was in many ways predicted by his princely career. The man was first and foremost a general. Under his father, he had spent many years marching out to various corners of the empire leading armies in the field of battle. His own reign can be described in precisely the same way. There was a restlessness about the man which time and again drove him to march out from his capital in all directions, even on those few occassions when strictly speaking there was no need for him to do so. But there can be no question that he was the right man for the times. During his father’s reign, the constant danger along the borders made his skills essential to the survival of the empire. These dangers were still very much alive when he himself came to the throne. His first concern as Great King was with the continuation of his campaigns against Arzawa. Word was brought to him that an Arzawan enemy had attacked the town of Aniša and then moved on to a town whose name is only partially preserved as [...]išša. So he marched forth and destroyed them. Continuing on his way, he then destroyed six enemy war bands at the town of Huwana[...], and seven more war bands at the towns of Ni[...] and Šapparanda. Another Arzawan enemy had moved into the land Tupaziya and onto Mt. Ammuna, where a man named Anna was helping them. Anna attacked Tupaziya and a lake whose name has been lost, and then managed to penetrate as far as Tuwanuwa, which he attacked. Clearly the Hittite situation was dire, since Tuwanuwa was located in southeastern Anatolia just north of the Taurus. That the Arzawans should be able to successfully campaign so far into the southeast indicates just how weak the empire had become. While Anna was attacking Tuwanuwa, Šuppiluliuma was occupied destroying the towns of Nahhuriya, Šapparanda, and another town whose name is lost. He then went to Tiwanzana “for sleeping.” In the morning he claims to have gone down from Tiwanzana with a small patrol consisting of only six other chariots. While riding he was confronted by “the whole enemy all at once.” This was probably a chance encounter rather than an intentional engagement (Beal (1992) 288f.). Nevertheless, he emerged victorious, and the enemy fled, abandoning their booty and taking up a defensive position on a mountain. From their height advantage they attempted to destroy Šuppiluliuma by raining arrows down on him. Šuppiluliuma chose to move up to Tuwanuwa at that time, where he was joined by his troops and chariots. At this point the text again becomes fragmentary, and we can only assume that Šuppiluliuma proved victorious over Anna and his Arzawan allies. The next fragment relates how Šuppiluliuma defeated an unknown Kaškan enemy. Two men, Takkuri and Himuili, are mentioned here. Šuppiluliuma had an officer named Himuili, so these two men were perhaps Hittite officers. In fact, this may be the very Himuili who played such a prominent role in the Maşat Hüyük letters, although this can certainly not be proven, and Himuili was by no means an uncommon Hittite name. After defeating this enemy, he went to the town of Anziliya (In the Kaškan region, not too far from Mašat). Then the Hittite towns of Pargalla, [...], Hattina, and Ha[...] were attacked by an enemy, so Šuppiluliuma went out and defeated them, restoring the Hittite people, cattle, sheep, and goods to their rightful places. After this, Šuppiluliuma had to turn his attentions to the west again due to yet another menace from that direction. A man named Anzapahhaddu, who may have been the king of Arzawa, captured Hittite territory. Šppiluliuma wrote the standard letter demanding the return of his territory and people, which was duly ignored by the Arzawan. So Šuppiluliuma marched against him. Something about the land of Mira is then written. This may perhaps be the expulsion of a ruler named Mašhwiluwa from Mira by his brothers. Mašhwiluwa fled to Šuppiluliuma as a fugitive, and Šuppiluliuma accepted him and gave him his daughter Muwatti as a wife. But after this, Šuppiluliuma was not able to assist Mašhwiluwa in restoring his lands to him because his attentions became absorbed with the Hurrian lands on the eastern side of his empire (Extended Annals Year 12). Šuppiluliuma’s change of venue may not have been completely voluntary. The broken text fragments make it clear that Šuppiluliuma was having difficulties recapturing land from Anzapahhaddu, and the ultimate outcome is not preserved. In spite of this, we can conclude that he must ultimately have been successful in capturing Arzawa itself, since he is known to have given the rule over Arzawa to a man named Uhha-ziti (Extended Annals Year 3). Further, Arzawa supposedly freed itself again while he was campaigning in Syria, which it could hardly have done if it had not been previously captured. One western land that Šuppiluliuma apparently did not have to campaign against was the land Wiluša. Although it stayed outside the Hittite vassal system, it remained at peace with the Hittites and maintained regular communications through messengers. This was apparently enough to prevent Šuppiluliuma from bringing his troops into that distant land. At this time Wiluša was ruled by a man that the Hittites called Kukkunni. Although this man seems to bear an Anatolian name, it may be better known from Greek sources. Various Greek sources present a Trojan hero by the name of Kyknos (with a false Greek etymology meaning "swan"), king of Colonae in the Troad, who was a son of Poseidon. This Greek Kyknos of the Trojan war was killed by Achilles and then transformed into a swan. Šuppiluliuma against Armatana: The next fragments mention a successful campaign against Armatana. Rebuilding & Remodeling Sometime around ~1400 B.C., the archaeological evidence at Boğazkale indicates that the citadel was rebuilt. We might suppose that this reconstruction followed the sacking of the city in the reign of Tudhaliya III. We do not, unfortunately, know exactly when the reconstruction began. Šuppiluliuma must have been involved, though, since he helped to recover the capital from the Kaškans. The citadel was not simply rebuilt, it was remodeled. The revived Hittite empire required a more impressive palace (Which at least suggests that the citadel was not rebuilt until the revival of Hittite fortunes under Šuppiluliuma). To this end the Hittites constructed huge terraces on the western and eastern side of Büyükkale in order to expand the area of the citadel plateau. The southern area of the citadel remained domestic in nature, but now most of the northern half seems to have been dedicated to palatial buildings. The palace itself stood at the upper, northern end: closest to the rocky cliffs and furthest from the southern gate. A central courtyard surrounded by a colannade formed its heart, and the royal apartments opened onto this courtyard. The new terraces of the plateau were occupied by other buildings and the cyclopean walls. Sometime shortly after his accession, Tadu-Hepa, the dowager queen, must have died, since Šuppiluliuma’s wife Henti became the Great Queen within three or four years of his accession. At this time we learn of two of Šuppiluliuma’s sons. His eldest(?) son Arnuwanda had already been designated as the heir to the throne. At this time (ca. 1342?) the next eldest son, Telipinu, was appointed as the Priest of Kizzuwatna. This decree was issued in the name of Šuppiluliuma, Great Queen Henti, prince Arnuwanda, and Zida Chief of the Royal Bodyguard (See Bryce (1992) 7). The role of Priest of Kizzuwatna has been mentioned already in the reign of Tudhaliya III, but the decree concerning Telipinu permits us to make a clearer assessment of this Hittite magnate. At this time the office of Priest of Kizzuwatna reveals itself to be a rather unique position. The Priest was required to have the same friends and enemies as the Great King. He had to reveal those who spoke or acted against the Great King. If he was involved in a dispute, it had to be referred to the Great King. The position appears to have been heritable, and Telipinu had to recognize Arnuwanda as the legitimate successor to the Great Kingship, and further he could not interfere with the succession. The last requirements could easily have been inserted simply because of the claim Telipinu could otherwise make on the throne, but the rest strongly resemble those required of vassal kings. But along with those requirements, there were religious requirements as well which fit his position as “priest”. How Telipinu’s responsibilities differed from those of his predecessor is unknown, but considering that a previous Priest of Kizzuwatna considered himself a Border Guard for the Great King, clearly Telipinu’s authority must have strongly resembled those of his predecessor. Perusal of the Priest’s duties reveal similarities with the duties held earlier by Madduwatta of Mt. Zippašla. Both had duties reminiscent of vassal kings, but considered themselves to be Border Guards. However, in the instance of Kizzuwatna, the position takes on a new character due to the religious duties placed upon its ruler. The need to keep a closer connection with the ruler of Kizzuwatna than with a typical vassal king, and the appearance of this tie through the priestly role, may have been influenced by the profound effect that the culture, and particularly the religion of Kizzuwatna was having on Hatti proper at this time. Telipinu’s role in the subsequent Great Syrian campaign, if he had one, is entirely unknown. Kingdom of the West

These words were written by an Egyptian scribe of the late 19th dynasty, but his words would have echoed true long before then. The land that he described, full of dark forests, ferocious beasts, and cowardly sneak thieves, was the raw material from which a small kingdom had sprung several centuries before this passage was written, namely the kingdom of Amurru. Amurru began its existence in the wild highlands of the Lebanese mountains. The semi-nomadic tribes that called the cedars of Lebanon home were an ever present menace to their more civilized neighbors on the coastal lowlands. There lay the great commercial cities such as Beruta (Beirut), Gubla (Byblos), Ardata, Ullaza, Irqata, Sumur, and their like. Since the conquests of Thutmose III, Sumur had replaced Ullaza as the most important imperial city in Egypt’s northern-most zone of control, and it had become the residence of the Egyptian comissioner who exercised his authority in the region now generally refered to by the local rulers as Amurru. Amurru’s political destiny was forever altered by an ambitious highland dynast who turned his eyes to the rich coastal cities that lay below him. He was destined to weld the highlands and lowlands into what would become the kingdom of Amurru, and establish a dynasty which would only disappear with the kingdom of Amurru itself and indeed with the Late Bronze Age era of which it had become such an important part. The man was named Abdi-Aširta. Calling upon the strength of dissidents in the Amurrite highlands, usually referred to generically as Apiru, Abdi-Aširta began his campaign to sweep down out of his mountains and capture the coastal cities of Amurru. Under his leadership, the Apiru killed Aduna, the king of Irqata. This victory did not evoke a response from Aduna’s Egyptian masters, and so subsequently Miya, the ruler of Arašni, seized the city Ardata for Abdi-Aširta. These two cities, Irqata and Ardata, gave Abdi-Aširta important southern strongholds from which to expand his conquests both northward and southward. The coastal city Šigata fell to him next. While several Levantine rulers were alarmed by his activities, the most prolific witness to Abdi-Aširta’s predations was Rib-Hadda, the ruler of Gubla. He saw himself as always on the verge of being overwhelmed by the Amurrites, and vociferously complained to his Egyptian overlords with every advance forward in the Amurrite dynast’s plans. As Abdi-Aširta emerged from his highland base as a local strongman, Rib-Hadda was there to complain about it. In letter after letter, he requested Egyptian military aid to protect him against the Amurrites. One such letter, written after Abdi-Aširta’s capture of Šigata, is addressed to the Egyptian official Aman-Appa, who had previously been posted in Sumur and may have been the man in charge of a garrison from Sumur which had previously been posted in Gubla, but which appears to have been withdrawn when Aman-Appa returned to Egypt. In this letter, Rib-Hadda tried to convince Aman-Appa how easily the Amurrites could be repelled, and how much that would restore Egyptian prestige in the area,

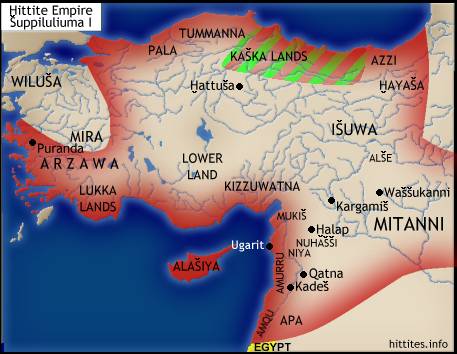

In fact, Abdi-Aširta’s message worked, and the men of Ammiya did indeed kill their lord and join with him (EA ##74, 75). This further expansion of Amurrite dominion occurred at just the same time that a new force entered the Syrian plain - the resurgence of Hatti under the leadership of Šuppiluliuma. Šuppiluliuma’s First Syrian Campaign A good map for Šuppiluliuma I’s Syrian campaigns can be found in Murnane, William J., The Road to Kadesh, SAOC 42, 1990, xvi. HDT = Beckman, Gary, Hittite Diplomatic Texts. Turning back to the Anatolian highlands, we find Šuppiluliuma shifting his vigorous attention in a new direction. With his Anatolian possessions momentarily secure, Šuppiluliuma now took account of the lost territories in the east. He secured a treaty with Artatama II, whom he called the “King of Hurri”, as opposed to Tušratta, whom he called the “King of Mitanni.” Artatama’s domain seems to have lain to the east of Tušratta’s, since the Assyrians were his subjects and paid tribute to him during the first part of his reign (HDT #6B §1). Tušratta now found himself uncomfortably pinched between two united foes. The Hittites would prove to be the ones who would initiate hostilities. Gathering together his army, Šuppiluliuma marched forth against his Hurrian neighbor. His first target was Išuwa. Išuwa had remained a Mitannian possession since Tušratta had repulsed the Hittites there in the reign of Tudhaliya III. Moreover it had remained a haven for the troops of all those many cities who had fled there. Šuppiluliuma now felt ready to avenge that Hittite humiliation. As it turned out, his confidence was somewhat premature. Instead of a grand tour of reconquest, he was only able to raid into Išuwa as far as the west bank of the Euphrates. Making no further progess in this direction, he turned south and marched against the Mitannian possessions in Syria. In this direction, Šuppiluliuma was able to march deep into Syria where he claimed to have taken Mitannian territory as far as Mt. Lebanon. This is somewhat disturbing in terms of Egyptian-Hittite relations, since this would seem to imply that he marched deep into Egyptian Amurru, past the latitudes of the Egyptian cities Sumur and Kadesh. Šuppiluliuma’s conquests must have come as quite an unexpected surprise to his contemporaries. After all, not long before the Hittites had seemed all but finished. In Gubla Rib-Hadda sent a dramatic summary of this alarming turn of events to the pharaoh, which, since it happened to coincide with his own problems with his northern neighbor Amurru, offered him yet another opportunity to express his own distress as well,

This response to Šuppiluliuma’s conquests, while clearly an overreaction, is certainly understandable. Tušratta could not let such a humiliating loss go unchallenged. He sent off an antagonistic letter to Šuppiluliuma, making the consequences of the Hittite king’s aggressions clear,

Presumably, this is precisely what he did. But before relating Šuppiluliuma’s response to these further Mitannian agressions, we must continue for a while the saga of the emergence of Amurru. After taking control of Ammiya, Abdi-Aširta turned his eyes southward against Gubla. Rib-Hadda reacted in his typically hysterical fashion, and in a letter to the pharaoh was not afraid to put damning words in his enemy’s mouth,

So, according to Rib-Hadda, Abdi-Aširta was willing to menace even the Egyptian pharaoh himself! We might be suspicious of poor Rib-Hadda and suspect him of a little alarmist propaganda inspired by his duress. And he does seem to have been hard pressed by the Amurrite, and for some time he had been making the same complaint to the pharaoh,

Little of Rib-Hadda’s kingdom remained to him. Abdi-Aširta had already taken all of his villages in the mountains and along the sea, so that besides Gubla he controlled only two other towns. Rib-Hadda’s distress was somewhat ameliorated by the fact that, while Abdi-Aširta was orchestrating hostilities against him, a much greater opportunity presented itself on his northern frontier. The troops of the city Šehlal, led by a man named Yamaya, launched an assault on Sumur and captured it while Pahanate, the Egyptian commissioner in Sumur, was away in Egypt. It is not known whether or not the unrest around Sumur was in any way connected with the recent Hittite annexation of territory in its vicinity. In any event, Abdi-Aširta was quick to seize the opportunity and, on behalf of the Egyptians, moved in and himself attacked Sumur, capturing the city in turn from Yamaya. At least, that was how he chose to present the situation to the Egyptians. But the Egyptian court was apparently barraged by a series of reports not only from other Syrian mayors, but also perhaps from some Egyptians (or some other class of people) who had fled Sumur when Abdi-Aširta took control of the city, and even from Yamaya himself. According to their version of events, it was Abdi-Aširta who was the aggressor, and he who had wrongly taken the city. Pahanate was initially swayed by Abdi-Aširta’s enemies, and sent a letter to the Ammurite accusing him of being an enemy of Egypt. Abdi-Aširta protested vigorously that his actions had been misinterpreted, and that in fact he was a loyal Egyptian subject, being vilely maligned by his enemies,

Rib-Hadda of Gubla, apparently somewhat stronger than he wished the Egyptian court to otherwise believe, took advantage of Abdi-Aširta’s abscence in the north to go forth and take away Šigata from him. But capturing Šigata and holding it were two different things. Rib-Hadda was promptly endangered by Egyptian pathos. The Egyptians in general do not seem to have been particularly interested in who ruled in the Syrian cities, so long as they professed loyalty to the pharaoh, and so they appear to have chosen to accept Abdi-Aširta’s authority in Sumur as a fait accompli. This freed him to turn his attentions southward once more. Now Rib-Hadda’s recent achivement came under threat. The Egyptians were clearly not reacting as he expected them to, and now he found his newly gotten gains in jeopardy. He needed Egyptian aid to hold back Abdi-Aširta, and anxiously wrote to Haya, the Egyptian commissioner over him, to find out about its arrival,

Yet the Egyptians did nothing, and Abdi-Aširta successfully recaptured Šigata and Ampi from the Gublite. Rib-Hadda once again found himself hard pressed by his Amurrite enemy, and once again sought assistance from the Egyptians,

Rib-Hadda’s words seem to have fallen on deaf ears. Or, at best, misled ears. Now that Abdi-Aširta had gained Egyptian recognition, he could more easily present his own version of events to the pharaoh, which of course contradicted Rib-Hadda’s. His attacks on Gublite territory continued, and Rib-Hadda became increasingly upset and confused by the Egyptians’ lack of response to his needs.

In addition to direct attacks against Gublite territory, Abdi-Aširta began forming alliances against Gubla. Rib-Hadda’s grain supply from the land of Yarimuta, upon which he depended so heavily, was cut off. After depositing a payment for grain with Yapah-Hadda of Beruta, the Egyptian commissioner Yanhamu claimed to have sent Rib-Hadda grain, but the grain failed to arrive. Rib-Hadda blaimed this on an alliance forged between Yapah-Hadda and Abdi-Aširta (EA #85). While all this was going on, new and disturbing events had taken place in Amurru. Abdi-Aširta had (perhaps) initially benefitted from the Hittite attack on Syria, taking advantage of the disorder created by it in order to expand his territory there. But now Tušratta was on the move, seeking to reassert his authority in Syria. Abdi-Aširta, who had probably seized some previously Mitannian territory from the Hittites, now found himself pinched between Mitanni and Egypt. He began playing a dangerous game of divided loyalties. He may initially have believed that he could, in fact, have maintained a duel allegiance; owing allegiance to Egypt for his Egyptian territories, and owing allegiance to Mitanni for his Mitannian possessions. Whatever he was attempting, he definitely opened relations with the king of Mitanni, and the king of that land entered Amurru. He may have simply done so to confirm his relation with Abdi-Aširta, but Rib-Hadda was convinced that the Mittanian king had further ambitions,

Rib-Hadda’s charge is usually dismissed, but in fact the Mittanian king may very well have planned on attacking Gubla in support of his new vassal. However, this must remain very uncertain. In any event, Rib-Hadda’s greatest concern remained the Egyptian recognition of Abdi-Aširta,

Rib-Hadda’s fortunes, however, were soon to change for the better, though he did not yet realize it. Abdi-Aširta’s relations with Mitanni would prove to be too much for the Egyptians to bear, as it hit them where it mattered most - their pocketbooks. Rib-Hadda would finally hit upon an accusation which would awaken Egyptian wrath against the Amurrite. Writing once again to the Egyptian official Aman-Appa, who apparently remained ignorant of the fact that the grain Yanhamu was supposed to send to him had never arrived (ll. 13-16), he claimed,

This was soon followed up later by the alarming claim that,

This was the crucial one-two punch that would finally turn the Egyptians against Abdi-Aširta. The Egyptians could not abide by a vassal who swore loyalty to another sovreign, and backed it up by paying tribute to him. The Egyptians would soon, finally, take action. But Rib-Hadda still had some unpleasantness in his immediate future. Indeed, for him, it was truly darkest before the dawn. Aman-Appa had Rib-Hadda send a messenger to him so that the pharaoh could provide him with troops and chariots. But his messenger returned empty-handed. Abdi-Aširta heard this, and was duly encouraged. He was soon in possession of Batruna, and threatening Gubla itself,

Rib-Hadda was now left with only Gubla itself. With his situation about as dire as it could possibly be, Rib-Hadda even requested that the pharaoh send him 1,000 shekels of silver and 100 shekels of gold, “so he will go away from me” (EA #91). But no such payoff was to come, and Rib-Hadda was almost out of time,

Indeed, Abdi-Aširta soon took control of the Gublite countryside,

Even more, Rib-Hadda was himself on the verge of giving up and surrendering to Abdi-Aširta,

But Rib-Hadda had now seen the worst. Egypt finally began to show signs that it was awakening to the threat posed by Abdi-Aširta. Even the commissioners seem to have become alarmed by Abdi-Aširta’s activities. Letters went out to the kings of Beruta, Sidon, and Tyre, saying,

While Rib-Hadda was immensely pleased by this, the expected troops were unfortunately late in showing up, naturally resulting in another letter to the pharaoh. But it seems probable that the reinforcements did finally show up. Things were changing in the Levant, and everyone seemed aware of Egypt’s new attitude towards Abdi-Aširta. Not only were local rulers expected to turn against Abdi-Aširta, including even the Amurrite cities, but even Aman-Appa himself finally sent word to Rib-Hadda to announce his immenent arrival. But Rib-Hadda had been given empty promises too many times in the past, and on the verge of his salvation he had some difficulty believing in this change in Egypt’s attitude,

But there would be archers. However, before the arrival of Egyptian troops, Abdi-Aširta first had to defend himself against local rulers such as Rib-Hadda and his comrades. With sentiment turned against him, it was now Abdi-Aširta who was on the defensive. He turned to his ally, the king of Mittani, for help,

It would do him no good. Abdi-Aširta would not survive his fall from grace. In fact, he now seemed incapable of spreading around generous gifts to his supporters, and unable to satisfy his Mitannian master, they turned against him. Betrayed by Mitanni, unable to support his followers, and with Egypt against him and sending forth troops to deal with him, his own people seem to have reassessed their situation, and then decided to dispose of their troublesome leader themselves, even before the Egyptian troops arrived.

Ironically, this preemptive strike against Abdi-Aširta made Amurru a pariah land, since they had acted without Egyptian authority,

Rib-Hadda had won. Against all odds, the great conquerer of Amurru had failed to capture him, and instead had been murdered by his own people. Rib-Hadda’s long struggle against Abdi-Aširta was over. Little could he know that he was about to wake from a bad dream into a nightmare. The Fight for Amurru Yet to be formulated into a narrative. Some relevant quotes, not in any particular order, are included here. Men of Arwada attacking Rib-Hadda(?):

Great Syrian Campaign Believed to have taken place ca. 1340, four years after his accession (Bryce (1992)). Šuppiluliuma began his epic campaign by crossing over to the east bank of the Euphrates and taking possession of the remainder of Išuwa. After annexing Išuwa he returned to their homelands the troops who had previously fled there. With Išuwa secured, he then turned south and seized the land of Alše and the district of Kutmar, and gave them to Mr. Antaratli of Alše. This left the district of Šuta exposed, in which was located the Mitannian capital Waššukkani. Šuppiluliuma promptly marched into the Mitannian heartland and wrote to Tušratta, “Come! Let us fight!” (DS #26) - but Tušratta chose to stay in his city rather than engage the Hittite. When Šuppiluliuma approached the Hurrian capital, Tušratta fled without giving battle, apparently retreating into Syria. However, Šuppiluliuma proved unable to capture the capital itself, and had to content himself with the plundering of Šuta. Tušratta’s flight into Syria seems to have involved more than simply a life saving retreat into his vassal properties. While there, he seems to have conducted military campaigns, presumably against unruly vassals who chose to use his discomfiture as an excuse to rebel against his authority. After devastating Šuta, Šuppiluliuma turned around and crossed back over the Euphrates, either in pursuit of Tušratta or in an attempt to take away his Syrian vassals. By entering Syria the Hittite Great King exposed himself to the Byzantine complexities of Syrian vassal politics. This region was terribly fragmented and its political structures seem to have been extremely unstable. This makes the reconstruction of events difficult. The reader must be warned that the following reconstruction of events is uncertain and other possibilities have been offered. Syria was the region where the Mitannian and Egyptian empires met. We can only wonder if the situation seemed as confusing to Šuppiluliuma as it does to us. In the event, Šuppiluliuma does not seem to have concerned himself overmuch with the subtlties confronting him. He was on a march of conquest, and made little effort to distinguish Mitannian vassals from Egyptian ones. This policy would ultimately lead him and his empire into generations of intermittent conflict with Egypt. It’s possible that after entering the Syrian vassal territories Šuppiluliuma’s first stop was the land of Nuhašši, which was ruled by several “kings of Nuhašši”. We know of two such kings, but do not know if there were any more. One of these kings was named Šarrupši, and the other was named Addu-nirari. Addu-nirari clearly considered himself an Egyptian vassal, but Šarrupši’s situation is more uncertain. Šarrupši came to fear for his life when Tušratta entered his territory. Since Šuppiluliuma was near to hand, Šarrupši wrote to the Hittite king, declaring, “I am the subject of the King of Hatti. Save me!” (HDT #7). The question that needs to be answered is, why was Tušratta trying to kill Šarrupši? A possible answer is that Šarrupši had been a Mitannian vassal up until the time of Tušratta’s discomfiture at Waššukkanni. At this time, Šarrupši might have tried to throw off the Mitannian yoke, perhaps in favor of an Egyptian one, or perhaps he turned to Artatama II. But the sudden appearance of Tušratta meant that Šarrupši needed help from someone immediately at hand, and so he turned to the Hittite king. In any event, Šuppiluliuma duly marched into Nuhašši, perhaps more out of a desire to face Tušratta in battle than to save a petty Syrian king. It is somewhat amusing to note that the Hittite entry into Nuhašši, which greatly alarmed the other Syrian principalities, was used by Aziru of Amurru as a convenient excuse to delay a potentially fatal journey to Egypt that the pharaoh had been demanding of him (EA #164). In any event, after entering Nuhašši, the Hittite army successfully drove out the beleaguered Mitannian emperor. But Šarrupši, for some reason, had turned on his savior. It’s possible that Tušratta had forced him to rejoin the Mitannian fold before the Hittites reached Nuhašši, and therefore the Hittites would have had to face him in battle. Although Šarrupši escaped (fleeing with Tušratta?), he did so at the price of leaving behind his mother, his brothers, and his children, whom Šuppiluliuma duly carted off to Hatti. In Šarrupši’s place Šuppiluliuma installed Takip-Šarri, one of Šarrupši’s subjects, as the king of the city Ukulzat in Nuhhašši. At some point Šuppiluliuma wrote a letter to Addu-nirari, the other known king in Nuhašši, asking for his submission. It is difficult to imagine that this was based on ignorance of Addu-nirari’s vassalage to Egypt. The unpleasant conclusion is that he was deliberately flouting Egypt’s authority. Addu-nirari knew the precariousness of his situation, but felt that he and his anscestors owed their position to the Egyptians. So he sent off an urgent message to the Egyptians explaining his situation and begging for aid,

He further started plotting against the Hittites. He joined with Itur-Addu, king of Mukiš, and Aki-Teššup, a king in Niya, and began attacking the territory of Ugarit, which had refused to commit itself to their anti-Hittite cause. Such behavior played nicely into Hittite hands. Šuppiluliuma sent a letter (HDT #19) to Niqm-Addu II, the king of Ugarit, demanding that, although the lands of Mukiš and Nuhašši were both hostile to the Great King, Niqm-Addu should be at peace with Hatti, as were his anscestors. The letter includes a not-so-subtle claim of lordship over Ugarit, when in fact Ugarit remained an Egyptian vassal. Nevertheless, Niqm-Addu resisted submitting himself to the Hittite Great King. Ugarit remained too far south to hinder Šuppiluliuma, so instead he moved further west and captured the city of Halap. It was probably at this time that he removed his son Telipinu from his position as Priest of Kizzuwatna and installed him instead as the King of Halap (Bryce (1992) 12). It was as the King of Halap that Telipinu would finish out his career. Interestingly, in spite of his move, his Kizzuwatnan title clung to him, and he remained known as “the Priest” for the rest of his life. While Šuppiluliuma was busying himself with Halap, the depradations of the kings of Mukiš, Niya, and Nuhašši finally became too much for Niqm-Addu II of Ugarit to bear. So he turned to the Hittite king for aid in return for his submission. Šuppiluliuma responded by sending troops and driving out the enemy. He himself marched against and captured Mukiš, seat of the long dead Idri-mi. In Ugarit Niqm-Addu gave precious gifts to the Hittite commanders who saved him and then went before Šuppiluliuma in Alalah, which remained the capital of Mukiš, and submitted to him there. For the first time a Hittite ruler had stolen away an Egyptian vassal. The incident would contribute to a souring of Hittite-Egyptian relations, but would not actually cause a rupture. In fact, nothing Šuppiluliuma did during this campaign would directly cause a breach between these two lands. It is possible that the Egyptians thought that diplomacy could be used to correct the situation rather than swords, and initial indications after the campaign would at first seem to have supported that view. During his stay in Mukiš, Takuwa, a brother of Aki-Teššup and described by Šuppiluliuma as “king of Niya”, came before the Hittite king for peace. But back in Niya his brother Aki-Teššup used the opportunity to seize his brother’s territory. Aki-Teššup and several powerful men named Hešmiya, Habahi, Birriya, and Nirwabi, along with their troops, joined forces with Akiya, the “king” of Arahati. Or at least he made himself such, since he and his cohorts’ first step was to seize the city of Arahati. Once in posession of this stronghold, they then initiated hostilities against the Hittite ruler. It was a poorly made decision. Šuppiluliuma marched against them, captured them all, and subsequently took them back to Hatti with him. After this victory, Šuppiluliuma turned south. His first stop on this leg of the campaign was the capture of the city of Qatna. After that he continued south into Apa (Apina, Upe), at least part of which was controlled by Egypt. From this point on, the land of Apa would prove to be the outermost limit of the Hittite empire, the armies of which would spill a great deal of blood here along with the Egyptians as they both struggled to stretch forth their empires to the furthest reaches possible. On the occasion of this conquest of Apa, Šuttarna, the Egyptian vassal king of Kadesh, apparently fearing for his life, came out along with his son Aitaqqama and attacked the Hittite king. Šuppiluliuma, swearing that he had not ever intended to attack Kadesh, nonetheless took advantage of the opportunity and overcame them in battle so that his enemies fled into the city of Abzuya. The city was duly beseiged and then captured, along with Šuttarna and his sons, brothers, chariot warriors, and possessions, which, of course, Šuppiluliuma would take back with him to Hatti. Ugarit had gone over to the Hittite side more or less willingly, but here the Hittites had outright attacked an Egyptian vassal. Šuppiluliuma’s only saving grace was that he had, after all, been attacked by Šuttarna, and this fact surely helped to ensure that relations between the two lands were not strained beyond repair. With Kadesh out of the way, Šuppiluliuma continued his march against Apa. The king of Apa at that time was named Ariwanna, and along with his noblemen Wambadura, Akparu, and Artaya, he gave battle to the Hittite conqueror. Šuppiluliuma was once again victorious and the defeated were destined to be deported to Hatti. This was the last march of the Great Syrian Campaign, about which in one text Šuppiluliuma proudly boasts,

After the Great Syrian Campaign One of the territories that remains remarkably absent from Šuppiluliuma’s records of his Great Syrian Campaign is that of Amurru. Possibly this is simply because Šuppiluliuma avoided this Egyptian territory, but then he did not seem particularly squeemish about upsetting the Egyptians in other lands. Another possible reason that it was left out was because Amurru simply did not wait to be attacked before it gave up. Something rather odd about the Great Syrian campaign is that we have no evidence for the return trip to Hatti. Hittite military strategy did not seem to call for a return home through friendly territory, and so the abscence of return campaigning is odd. This oddity can perhaps be made comprehensible if we place the submission of Amurru to the Hittites as the last leg of the Great Syrian campaign. Its absence from the historical record may arise from the fact that this remarkable submission was rather - unremarkable. Šuppiluliuma had had to violently crush resistence in the Syrian territories through which he marched - except in Amurru. In Amurru Aziru sought and succeeded in avoiding a Hittite thrashing. At the same time, he significantly changed the nature of his power and indeed the very political foundations of Amurru. Early in his career, and all through his Egyptian experiences, Aziru had remained simply the most prominent of the sons of Abdi-Aširta. But this was not a political situation which was consistant with Hittite concepts of rule, and Šuppiluliuma did not permit its continuance,

The kingdom of Amurru was born. In this way some century and a half of Egyptian effort in Amurru ended in failure. Lost were the great port cities of Sumur and Ullaza, lost were Irqata, Ardata, and Tunip, and lost were the dark, rich forests of highland Lebanon. They had all simply been handed over to an upstart Hittite king. It had taken generations of bloodshed for the Egyptians to create some semblence of order in Amurru, but it didn’t take the single swing of a blade for the Hittites to gain a kingdom. And sitting on top of all of it, Aziru emerges as the uncontested victor. Aziru’s voluntary submission to Šuppiluliuma actually created some problems for the Hittite scribes responsible for drawing up the vassal treaty. They had little practice in dealing with such a situation. As such, Aziru’s treaty, found in three Akkadian versions and one Hittite version, is a curious combination of generic features in an unusual structure. There was little need for a historical background justifying the Hittites annexation of the kingdom, and so this section did not play the preeminent role that it does in other treaties. In fact, it was not even the first section of the treaty. Since Aziru had submitted himself to the Hittite king, the treaty begins with his oath of personal loyalty to the Hittite dynasty. Included in this is, significantly, the statement of his annual tribute obligation of 300 shekels of the highest quality gold, weighed out in accord with the standards of Hittite merchants. Amurru, after all, was first and foremost a land rich in trade. Only after these obligations was the historical “preamble” written down. As preserved it does little more than record that Aziru’s submission was voluntary and that Šuppiluliuma therefore made him king of Amurru. It also seems to have recorded the speech which Aziru made when he submitted to Šuppiluliuma, but this section of the treaty is unfortunately poorly preserved. After this the treaty becomes rather standard. Aziru had to keep the same friends and enemies as the Hittite king, and he had to wholeheartedly support the Hittite king’s efforts against his enemies by mobilizing his own troops. Neutrality was definitely not an option,

Aziru was likewise forbidden to write to an enemy to warn him of an impending Hittite attack. Other obligations followed. He had to ransom any captured Hittites he knew about and promptly send them back to Hatti. It was not merely foreign aggression Aziru had to resist. If any internal rebellions occurred, Aziru (or at least one of his sons or brothers) likewise had to wholeheartedly come to his king’s aid. Šuppiluliuma likewise promised to send troops to Aziru’s aid should he experience any such difficulties. In spite of Aziru’s voluntary submission (in fact, Šuppiluliuma disingeuously says because of it), Amurru became an occupied land. Šuppiluliuma sent forth imperial trooops to ʻprotect’ his new vassal,

Then followed rather standard clauses about Aziru’s obligation to return fugitives to Hatti, even though the Hittite king had no such reciprocal obligation. But should Aziru ever desire anything, he should simply ask, as long as he was willing to accept whatever the Hittite king actually chose to give him. Aziru had to seek only the prosperity of Hatti, not that of any other land. The Hittite version ended with the declaration that the Thousand Gods were called to assembly to witness the oath, but the Akkadian versions went on to enumerate these gods by either name or catagory and topped it all off with perfunctory curses and and blessings. After Šuppiluliuma’s Great Syrian Campaign, the Hittite presence in Syria was largely withdrawn. The Hittite empire had made its might felt in Syria, but had left the region to gather itself together and take stock of its situation. A severly weakened Mitanni was about to undergo a trial of survival which it would ultimately lose. Since the Hittites didn’t leave a strong presence, and the Mitannians didn’t present a promising source of protection, the Syrian kings turned their attentions, and their loyalties, towards Egypt. Akizzi, king of Qatna, returned his loyalties to Egypt almost as soon as the Hittites had left. His letter to Ahen-aton trying to make good his losses is an intimate portrayal of what happens after the great battles of history.

Peace in Amurru - for the moment Akizzi’s problem with Aziru of Amurru and the king of Hatti highlight how important it was becoming for the Egyptians to deal with the Syrian problem. They had to take action. Since Šuppiluliuma’s defeat of Šuttarna of Kadesh, Šuttarna’s son had taken control of Kadesh. Aitaqqama insisted on his loyalty to the pharaoh, but he must have owed his return to power to the Hittites, and this would have made him look very suspicious to the Egyptians. So he was summoned to the Egyptian court where they could try to feel out his loyalties. The Egyptians were also willing to entertain the idea of the submission of Aziru, but they had had enough of his delays. They strongly insisted that Aziru travel to Egypt in order to petition for official appointment as the HAZZANU-official of Amurru. The future of Amurru was at stake. The trip was not a formality. While in Egypt Aziru would have to defend himself before the pharaoh against the accusations of his enemies. Rib-Haddu of Byblos was, of course, one of his principal opponents, and Rib-Haddu’s follower Ili-Rapih of Byblos sent a letter outlining Aziru’s crimes of assassination, conquest (specifically Sumur and Ullaza), and further that, even now, Aziru was in Egypt plotting with Aitaqqama of Kadesh. In spite of these accusations, Aziru met with approval, and the Egyptians granted him his appointment. The house of Abdi-Aširta had successfully gained recognition in the province of Amurru once again. “There was Confusion Among the Hurrians” Tušratta’s disastrous defeats at Hittite hands unleashed the forces of opportunism in the Mitannian empire. Sometime after the Great Syrian Campaign, perhaps as soon as the following year, Tušratta fell victim to a conspiracy by one of his sons in league with some of his subjects. Šuppiluliuma interpretted the assassination of Tušratta as the resolution of the dispute between Artatama and Tušratta, and he therefore recognized Artatama as the legitimate king of Mitanni. But Artatama, perhaps due to age, was no longer in control of his throne. Now his son, Šuttarna (III), seems to have either ruled in his father’s name or as a co-regent. But all was not well in the land of Mitanni. As the Hittites put it, “there was confusion among the Hurrians”. Previously Artatama had been forced to make payments to Assyria and Alše in order to secure his position as “King of Hurri”. Now Šuttarna, in possession of Tušratta’s palace as the king of all Mitanni, continued this tradition, emptying out the treasures that Tušratta had managed to horde in his brighter days;

With this humiliating banality towards the Assyrians, the proud traditions of the Hurrian court at Waššukkanni waned. Even Waššukkanni itself was beginning to fade in favor of alternately two other rising cities, that of Taite, mentioned just above, and soon, Irrite. At some point Šuttarna seems to have chosen the city Taite as his capital city. Such behavior naturally led to insurrection, and so Šuttarna set about cleaning his house of dangerous elements. Some of his oppenents fled to foreign lands. Two hundred chariots led by a man named Aki-Teššup fled to Babylonia. Among his retinue was a man named Kili-Teššup, one of Tušratta’s sons. Kili-Teššup would eventually return to his homeland and try to restore his family’s position. But Fortune still had more troubles in store for him, and at this time the Hittites were concerned with the current situation, not with the aspirations of a princely exile. Initially Šuppiluliuma maintained good relations with the new Mitannian regime. After all, the Mitannian throne was now in the hands of his treaty partner, Artatama, and his son. Some of this early good will bubbled up later when Šuppiluliuma actually made the remarkable claim, “I, Great King, Hero, King of Hatti, had not crossed to the east bank, and had not taken even a blade or a straw or a splinter of wood of the land of Mitanni.” What technicality allowed Šuppiluliuma to make this astonishing statement is difficult to comprehend. Apparently, he viewed post-Tušratta Mitanni as a seperate entity from what had been before. In any event, his friendliness consisted of more than mere words. When it became clear to him that the land of Mitanni was falling into poverty, he sent cattle, sheep, and horses to its relief. For the moment, the Hittites enjoyed peace with their eastern neighbors. Trouble in the south seems to have been avoided as well. In spite of Šuppiluliuma’s annexation of Ugarit, Kadesh, and Amurru, relations with Egypt continued, albeit under strained conditions. The death of Ahen-aton set in motion a political crisis in Egypt which strained these relations even further. Smenhkare, Ahen-aton’s successor, failed to continue the practice of gift exchanges between the two lands. Šuppiluliuma wrote a contentious letter to Smenhkare reminding the new pharaoh of the previous friendly relations between the two lands and how nothing that was asked for by one was held back by the other;

Except for this letter, and some vague references to Hittite activity in Syria under the leadership of a Hittite commander named Lupakki who campaigned in Amqa, we now run into a lull in our available information. Unfortunately, this “lull” could cover more than 10 years - approximately the gap between his Great Syrian Campaign and his Second Syrian Campaign. At some point in this gap, Šuppiluliuma’s relations with Šuttarna of Mitanni appear to have fallen apart, but we do not know exactly when or why. But the stage for such a conflict had already been set. Having a treaty partner who paid tribute to other foreign powers was surely a source of concern and a blow to the Hittites’ own prestige. Further, the subordinate position of the Hurrians could have meant that the Assyrians could have pressured them towards an anti-Hittite policy. But the next information available to us does not concern the far east, but rather the north. Troubled Northern Lands Where the Deeds resumes, approximately two to four years before the Second Syrian War, we find Šuppiluliuma “returning” to Mt. Zukkuki, back in the Kaškan lands in the north. While at Mt. Zukkuki Šuppiluliuma fortified the towns of Athulišša and Tuhupurpuna. While he was doing this, the Kaškans continually boasted that, “By no means will we let him down into the land of Almina!” But Šuppiluliuma had plans to the contrary. Upon completion of the fortifications, he did indeed go down into the land of Almina, wherein he soundly defeated his cocksure enemies. After this victory, he began the fortification of the city of Almina. He also organized the Hittite command of the territory, situating himself on Mt. Kuntiya and placing Himuili, the Chief of the Wine, at the Šariya River and Hannutti, the Chief of the Chariot Fighters, in the town of Parparra. For an unspecifed amount of time all of Kaška was at peace, Hittite subjects established hostels in unwalled Kaškan towns or returned to their own towns, and the fortifying of Almina continued. Not one to sit at home, Šuppiluliuma used this repast to extend his conquests even further. He sent out Urawanni and Kuwatna-ziti, the Chief Shepherd, against the land of Kašula. With the help of Šuppiluliuma’s gods, the commanders were victorious and returned with 1,000 civilian captives, cattle, and sheep. Unfortunately, a plague broke out in the army, and the Kaškans seized not only the opportunity, but also the Hittites who were in their towns. Whoever they didn’t capture they killed. They then turned against the Hittite fortified camps that were in their land. But they were not strong enough to withstand the roused Hittite might, and were pacified once more by healthy Hittite armies. With little fanfare the Deeds then go on to relate that Šuppiluliuma “conquered all of the land of Tumanna, fortified it, organized it, and made it part of Hatti again.” Small praise for the reconquest of such an important territory. This terse statement is somewhat supplemented by the Annals of Muršili II (Year 16), where he states that Šuppiluliuma had sent his nephew, Hutu-piyanza, son of Zita, into the land of Pala. At this time Pala had not been fortified in any way by the Hittites. So Hutu-piyanza, in spite of the fact that he didn’t have a large force at his disposal, set about defending and fortifying the land of Pala. They were forced to use guerrilla tactics, constructing hideouts in the mountains, but in spite of these difficulties they didn’t yield any of the land to any enemies. After this, Šuppiluliuma returned to Hattuša to pass the winter there. After the celebration of the new year, he marched north once again. This time he marched against Ištahara, an important northern city that Kaškans had captured. He appears to have reconquered not only of Ištahara, but also Manaziyana, Kalimuna, and another town whose name is lost. All of these towns seem to have been (or become) subordinate to Ištahara. This seemingly insignificant campaign and reorganization must have been much more difficult than it appears to us, because it appears to have taken up the entire campaign season for the year, since Šuppiluliuma returned to Hattuša afterwards. While Šuppiluliuma’s attention was focussed in the north, far to the south his Syrian possessions were being attacked by war parties (In the year after the Ištahara campaign?). His son Telipinu, the King of Halap, successfully defended Hittite interests against them. As a result the territories controlled by the cities of Arziya and Kargamiš made peace with him, and so did the city of Murmuriga. The city of Kargamiš itself, however, refused to make peace with Telipinu. So Telipinu left 600 troops and chariots in Murmuriga under the command of Lupakki, the Commander of Ten of the army with whom we have met earlier, and then left for Hattuša in order to consult with his father. But because Šuppiluliuma was performing religious ceremonies in the city of Uda at the time, Telipinu altered his course and met with him there instead. The Third Syrian Campaign Once Telipinu left Murmuriga, the troops and chariots of Hurri came and beseiged the city and overwhelmed its garrision. At the same time, the Egyptians chose to reassert their authority in Syria by force and attacked Kadesh. It is likely that Nuhašši also went over to the Egyptians at this time. The situation called for a response by the Great King himself. In 1327 he gathered his troops and marched to the city of Talpa in the land of Tegarama, where he conducted a troop review. But instead of marching against the Hurrians himself, he sent out his brother Zita, Chief of the Royal Bodyguards, and the crown prince Arnuwanda against them. These two men defeated the Hurrians in battle, and the enemy fled. This victory enabled Šuppiluliuma to undertake a much more important march; that against the city of Kargamiš. Šuppiluliuma marched down to and laid seige to Kargamiš. While there he sent Lupakki and a man named Tarhunta-zalma south against the land of Amqa in response to the Egyptian capture of Kadesh. They successfully brought back civilian captives, cattle, and sheep. The news of the attack on Amqa reached the Egyptians at a time which, from the Hittite point of view, can only be considered extremely fortuitous. Tut-Anh-Amon, the young Pharaoh of Egypt, had just died. A Queen Without a King The death of a king is usually a time of crisis in any empire, and the Egyptians were no exception. The death of Tut-Anh-Amon, who had no son, brought out the worst in Egypt’s upper class. The widowed queen felt that she could not trust her own subjects, so she wrote to the only person who seemed powerful enough to save her; the enormously successful Hittite general currently ransacking Egypt’s territories at his will. So, while in the midst of his seige of Kargamiš, Šuppiluliuma received an extrordinary letter from Dahamunzu, Tut-Anh-Amon’s widow:

Šuppiluliuma was so surprised by this message that he called together his commanders for council and declared, “Such a thing has never happened to me before!” He decided to send forth Mr. Hattuša-ziti, the Chamberlain, to Egypt to make sure that the message was not a deception, that there truly weren’t any sons of Tut-Anh-Amon. While awaiting a reply, and somewhat anti-climatically considering what else was going on, Kargamiš finally fell to the Hittites after a seige which had only lasted into its eigth day. Šuppiluliuma preserved the city’s citadel, even worshipping there a Tutelary Deity and another deity whose name has been lost, but was probably Kubaba, the city’s patron goddess. But the rest of the city was not spared. The Great King personally claimed to return to Hattuša with silver, gold, bronze implements, and 3,330 civilian captives. He simply states the booty taken by his men was without number. Before returning to Hattuša he returned the land of Kargamiš to that city’s jurisdiction and made yet another son of his, Piyaššili (also known as Šarri-Kušuh), into a king; the King of Kargamiš. In this way Kargamiš began a long career as one of the most important of Hittite cities. The following spring Hattuša-ziti returned to Hatti along with a messenger from Egypt called lord Hani. To the Great King’s inqueries the Queen of Egypt replied,

This time Šuppiluliuma complied. He brought forth the old treaty between the Hittites and Egyptians which related how the Storm God took the citizens of the Hittite city Kuruštama and carried them into Egypt to become Egyptians, and how the god established peace between Hatti and Egypt. On this basis, Šuppiluliuma declared a new friendship between Hatti and Egypt, and sent off one of his sons to marry the Egyptian queen and become the king of Egypt. The Deeds call him Zannanza, which it has been speculated is actually a Hittite transliteration of an Egyptian title. It’s worth pausing now to contemplate Šuppiluliuma’s achievement. Simply put, it’s astonishing. Never in the ancient world had a kingdom had the opportunity to hold dominion over such a vast territory, stretching from the western shores of Anatolia, deep into Syria, all of Palestine, and on south down the Nile. Of the four great powers in the Near East at Šuppiluliuma’s accession - Hatti, Mitanni, Babylon, and Egypt - the Hittite Great King was on the verge of becoming the emperor of three of them. This was surely the most spectacular moment in Hittite history. But history had its own cruel tricks in store for the Hittites. The Deeds become fragmentary, but it is clear that something went wrong. Šuppiluliuma accused the Egyptians of killing Zannanza and attacking Hittite territory. A fragmentary letter concerning this incident has actually survived in which is recorded an Egyptian plea of their innocence in Zannanza’s death. It was to no avail. The death of Zannanza meant war, and Šuppiluliuma submitted his case to the Sun Goddess of Arinna and the Storm God for judgement. The sporadic hostilities between these two lands would touch a further four generations of Hittite rulers. The Final Campaigns of Šuppiluliuma The immediate Hittite response to Egypt’s perfidy is unknown. The fragmentary letter concerning the matter seems to indicate a period of belicose correspondence before hostilities were actually initiated. Where the Deeds next resume Šuppiluliuma is not in Syria at all, but back in northern Anatolia. For the rest of his reign Šuppiluliuma would have to fight in order to retain his earlier conquests. He is seen campaigning in all of the places that he previously campaigned in except the Arzawan territories. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be because he retained control of this territory. Arzawa seems to have slipped out of Hittite control. Uhha-ziti freed himself and became an ally of the King of Ahhiyawa instead. Not too many years later Šuppiluliuma’s son Muršili II would indicate that either Šuppiluliuma or Muršili’s brother Arnuwanda II (the name is unfortunately lost) had to station troops in the Lower Land in order to defend against Arzawa. Where the Deeds pick up, Kaškans are mentioned and Šuppiluliuma burned down several towns, the name of two of which, the towns of Palhwišša and Kammama, are preserved. After this, Šuppiluliuma is seen campaigning in a great many obscure places in the north. He is found in Ištahara again, although it is uncertain if he was attacking it or just passing through it on his way to enemy territory. Teššita and other lands were burnt down. He refortified the city of Tuhpiliša. While he was there the people of Zidaparha unsuccessfully tried to influence the course of his campaign so that he would not enter their land. Šuppiluliuma marched on to Tikukuwa and stayed there for awhile before moving on to Hurna. He stayed in the city of Hurna and burned down its territory. He burned down a territory in Mt. Tihšina. This long list of obscure places is then momentarily relieved by the mention of the River Maraššanta. But we are immediately plunged into obscurity again when he moves on into the peaceful land of Darittara. A man named Pitakkatalli mobilized troops in the town of Šappiduwa, but Šuppiluliuma marched against him and defeated him. He then moved on to the town of Wašhaya in Mt. Illuriya and stayed there awhile. He burned down Zina[...]. He moved on and burned down Ga[...]kilušša and Darukka. He burned down the lands of Hinariwanda and Iwatallišša and remained in Hinariwanda awhile. He then reached and burned down Šappiduwa itself. This at least suggests that the list of places starting with Mr. Pitakkatalli at Šappiduwa was part of a single campaign. After destroying these lands, Šuppiluliuma decided to expand his northwestern conquests. To this end he went to Tumanna, ascended Mt. Kaššu, and then marched out against [...]naggara. River Dahara Land revolted, so Šuppiluliuma burned it down and Tapapinuwa as well. He then turned back to Timuhala. Timuhala, “a place of pride of the Kaškans,” didn’t wait to be attacked before it surrendered. The badly divided lands of the north simply could not resist a Hittite imperial army. Hittites, Hurrians, and Assyrians Meanwhile, on a completely different front, the tribulations of the house of Tušratta continued. The reception of Aki-Teššup and his contingency in Babylonia was less than what they could have hoped for. The Babylonian king took away Aki-Teššup’s chariots and possessions and forced him to assume the rank of one of his charioteers. Finally it seems that he simply wanted to kill Aki-Teššup (Perhaps as a means of cementing relations with Šuttarna III’s dynasty?). The situation of the fugitive Hurrians in Babylonia was clearly deteriorating. Tušratta’s son Kili-Teššup, fearing for his own life, fled from Babylonia and sought refuge in, of all places, Hatti. Of course, since relations between Hatti and Mitanni had changed in the intervening years, when Kili-Teššup reached the Maraššantiya River with only “three chariots, two Hurrians and two other attendants who set out with me, and a single outfit of clothes, which I was wearing, and nothing else”, and threw himself at Šuppiluliuma’s feet, the Great King’s reaction to his old nemesis’s son was not what one might have expected. Šuppiluliuma took him by the hand, rejoiced over him and questioned him at great length concerning the customs of Mittanni. Šuppiluliuma chose to help himself by helping Tušratta’s son. He now saw a way to secure his own blood line on the throne of Mittanni. He promised Šattiwaza,

To this, he added a comment which seems somewhat farcical to us, who know something of his earlier history,

Tudhaliya the Younger and the Egyptians may have been of a different opinion. Unfortunately, in this particular case, his vow to Šattiwaza left Šuppiluliuma in a bit of a pickle. For he had already recognized Artatama as the legitimate ruler of Mittanni. But the example of Šuttarna’s rule guided him to a compromise which would allow him to assist Kili-Teššup without being accused of bad faith towards Artatama. Šuppiluliuma agreed that, if he should overcome Šuttarna in battle, then Kili-Teššup would take Šuttarna’s place as the successor of Artatama and ruler of Mitanni,

The only detail remaining to be explained was how Šuppiluliuma would “adopt” Kili-Teššup as his son. This seems to be an indirect reference to the Hittite custom of antiyant-husbandship, and Šuppiluliuma’s treaties with Kili-Teššup stronly emphasize the importance of the position of a daughter who Šuppiluliuma gave to him in marriage (discussed in detail below). After receiving rich gifts, including chariots mounted with gold and armored chariot horses to pull them - and some new clothes - Kili-Teššup was entrusted to Piyaššili, the King of Kargamiš, as one of his chariot warriors. The two men made their way to Kargamiš and then set out on a campaign to place Kili-Teššup on the Hurrian throne. Piyaššili’s and Kili-Teššup’s campaign against Šuttarna began as every proper campaign began, with a letter to their intended victims, the people of the city of Irrite, located in the land of Harran. But Šuttarna had already purchased their loyalty, so they wrote back to the Hittites, “Why are you coming? If you are coming for battle, come! But you shall not return to the land of the Great King!” Having made their token effort at a peaceful resolution, the Hittite army crossed the Euphrates, burned down the territory of Harran, and approached the city of Irrite. The imperial troops of Mitanni and the local chariotry of Irrite were waiting for them. When the Hittite army arrived, the Hurrians came out of the city and attacked them. The ensuing battle went to the Hittites, and thereafter the people of Irrite and of Harran, too, came to the Hittites to sue for peace. Meanwhile Šuttarna’s hold over Mitanni seems to have been slipping. The Assyrians sent forth an army under the command of a chariot fighter to pacify the city of Waššukkanni itself. The citizens refused to make peace, so the Assyrians laid siege to the city. Piyaššili and Kili-Teššup were in Irrite at the time, so the people of Waššukkanni sent a message saying that the Assyrians had come for battle against the Hittites. Piyaššili and Kili-Teššup promptly marched to Waššukkanni. The Assyrians, however, were not ready to tangle with the mightiest empire of the day, and they prudently withdrew. So the Hittites victoriously entered and took possession of Tušratta’s old capital city. Another nearby land, that of Pakarripa, became frightened and submitted to the Hittites, so Piyaššili and Kili-Teššup left Waššukkanni and marched to Pakarripa. While they were there another message was brought to them saying that the Assyrians were coming against them for battle. In spite of the fact that the desolate environs of Pakarripa were unable to provide sufficient sustenance, the Hittites marched out in search of the Assyrians. They got as far as a city called Nilapšini, but again the Assyrians did not come out against them for battle. It is not known if the Assyrians ever faced the Hittites at this time. The Hittites marched against Šuttarna at the city of Taite, and the Assyrians, hearing of this, supposedly marched there. But this may simply have been one more false rumor circulating about the Assyrians, and the only two texts that discuss this campaign both break off at this point. If nothing else happened at this time, then it is clear that the Assyrians did not feel up to the challenge of taking on a Hittite army yet. It would be one of the last times that the Assyrians would react so docilely to the Hittite threat. For the time being the final result was that Šuttarna disappears from the historical record, and Kili-Teššup took his proper place in Mittanni as Artatama’s successor and the ruler of Mittanni. Šuppiluliuma secured two treaties with Kili-Teššup, one from Šuppiluliuma’s point of view, and another from Kili-Teššup’s point of view. It’s interesting to note that, at the time these treaties were drawn up, Artatama was certainly still the nominative king of Mittanni, since Kili-Teššup is only referred to as a “prince”. Also of importance is that Kili-Teššup took for himself the throne name of Šattiwaza. Like that of several of his predeccessors, this name is of Indo-Aryan etymology. But not just his name is Indo-Aryan. In his treaties, he invokes, among the many Hurrian and Mesopotamian deities, the Indo-Aryan deities Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and the Nasatyas. As mentioned above, the principal means of securing the relation between these two men seems to have been through the action of having Šuppiluliuma take him as a son by means of making him into an antiyant-husband for a daughter of his. By doing this, Šuppiluliuma was able to install a “son” of his on the Mittannian throne, and secure the succession in Mittanni for descendents of his own line,

The last bit about Šattiwaza’s descendents by Šuppiluliuma’s daughter being the equals of Šuppiluliuma’s own descendents supports the conclusion that this was an antiyant-husband marriage, in which Šattiwaza became a member of Šuppiluliuma’s family, rather than his daughter a member of Tušratta’s. In this light, it is useful to note that Šattiwaza emphasized his poverty when he first approached Šuppiluliuma, coming to him with “only three chariots, two Hurrians, two other attendants, who set out with me(!), and a single outfit of clothes - which I was wearing - and nothing else.” (HDT #6B, §4). In the normal course of events, it was poor men who were taken as antiyant-husbands. The next fragment of the Deeds mentions crown prince Arnuwanda, being sent to “Egypt” (i.e. that part of Syria controlled by Egypt). The following fragments mention Irrite, Waššukkanni, and a Hurrian victory over Hittite troops. Hayaša seems to have offered its submission again. If it did, it must have almost immediately cast off the Hittite yolk. Irrite, Kargamiš, and Waššukkanni are mentioned yet again, and it is probably at this time that certain Hittite subjects fled into the land of Azzi. They would remain there until well into the reign of Muršili II. This may also be the time when a great deal of Kaška began to raid Hatti, while Šuppiluliuma was campaigning in “the Hurrian lands” (alternatively called Mittanni in Muršili’s Annals). Then, in the last fragments preserved of the Deeds, Išhupitta and Kašipaha are mentioned, which seems to indicate that he began the reconquest of the north. He would not live to finish the task. Death of Šuppiluliuma

What man could not bring down, Nature did. Or, as the Great King’s son Muršili came to believe, the gods did, in order to avenge the death of Tudhaliya the Younger, that long deceased brother betrayed and murdered by Šuppiluliuma and his fellow conspirators. The instrument of the gods’ wrath would be another victim of Šuppiluliuma’s betrayal. The Hittite army which had been campaigning in Amqa brought back to Hatti Egyptian troops as prisoners. But they brought a plague back with them. Šuppiluliuma fell victim to this plague soon after. His chosen heir, crown prince Arnuwanda, succeeded to the throne without difficulty. The reputation of his father, and the fact that he himself was a mature and experienced military commander, was enough to guaruntee the good behavior of the vassals. Šuppiluliuma I was possibly responsible for the refounding of Emar when the river course changed. Or it could have been his son, Muršili II. Foreign Relations Ahhiyawa: Friendly at beginning of Šuppiluliuma’s reign. But eventually Millawanda rebelled with Ahhiyawan assistance. Mira and Šeha River Land involved. Arzawa: Arzawa peaked with its attack on Tuwanuwa in southeastern Anatolia. Šuppiluliuma appears to have driven the Arzawans under Anzupahhaddu back into the west and even to have subjugated them. It freed itself during the Hurrian War (Campaigns related to the siege of Kargamiš), but no longer posed a threat to Hittite security. It allied itself with Ahhiyawa. Kizzuwatna: Part of the Hittite realm. Šuppiluliuma installed his son Telipinu the Priest of Kizzuwatna in Kizzuwatna, and Telipinu later led troops to Šuppiluliuma’s support in his Syrian campaigns. (CTH incorrectly places the Šunaššura treaty in Šuppiluliuma I’s reign (#41). It belongs with the earlier king Tudhaliya II) Išuwa: Recovered by Šuppiluliuma (CAH 2.2 pg. 6.). It took two battles, one against the Išuwans, and then against the Išuwans and Tušratta of Mitanni. Wiluša: Šuppiluliuma I, under his father, Tudhaliya III, campaigned in Arzawa. He did not, however, have to campaign against Wiluša, since its king, Kukkunni, remained friendly with the Hittites, per tradition. See The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. Hayaša: (Along with Azzi) A territory situated somewhere in north-eastern Anatolia. Before becoming king, Šuppiluliuma marched against this territory. He later marched against it as part of his Great Syrian campaign. Šuppiluliuma made a treaty with Huqqana, whom Šuppiluliuma raised from an obscure stature to that of the foremost man among the Hayašans (not a king) (Beckman (1996) 22f.). Šuppiluliuma married his sister to him, and then, in the treaty itself, instructed Huqqana that when her relatives visited her in Hayaša, he was not permitted to sleep with them, as he believed Hayašan custom permitted. |

|

| Some or all info taken from Hittites.info Free JavaScripts provided by The JavaScript Source | |