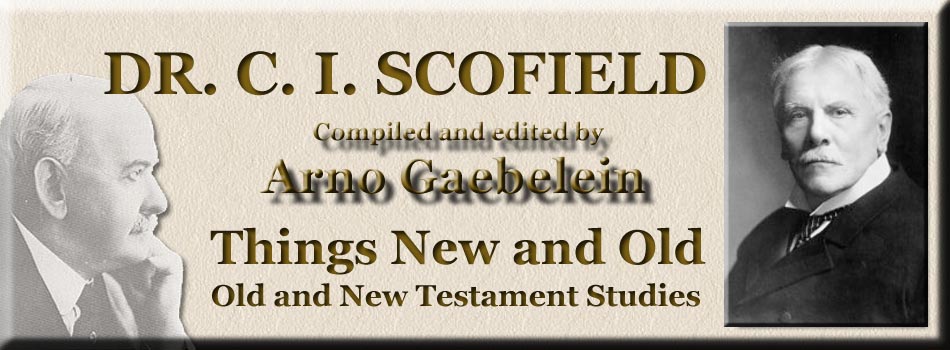

Things New and Old

By Cyrus Ingerson Scofield

Compiled and Edited By Arno Clement Gaebelein

Old Testament Studies

DANIEL AND BELSHAZZAR.(Daniel v:17-30.) I. The Analysis. 1. The Unheeded Lesson of History (verses 17-24). Daniel rehearses to Belshazzar the well-known circumstances of his father's reign. The impressive lessons of that history Belshazzar had passed by unheeded. Now nothing remains but his deposition. 2. The irreversible sentence (verses 25-30). Belshazzar was yet a very young man. It is one of the fearful things about sin that the human heart may become hopelessly set in the love of it at a very early age. II. The Heart of the Lesson. We must bear in mind the peculiar circumstances under which the prophet Daniel writes. He was a Jewish prophet, but a prophet out of the land. Israel, under the chastening hand of Jehovah, often warned, but apostate and unheeding, has been given into captivity under the Babylonian power of Nebuchadnezzar. With the captivity, and with the empire of Nebuchadnezzar begun that long period of Gentile world-empire which our Lord designates as "the times of the Gentiles'' (Luke xxi:24), which still continues, and which will continue till "the God of the heavens" (Daniel ii:44) shall smite with judgment the whole fabric of Gentile civilization and authority, and set up a kingdom which shall never be destroyed (Dan. ii:44; vii:14-18). The visible token and sign of the continuance of the times of the Gentiles is that Jerusalem is under alien and Gentile domination. That domination, be it remembered, is not broken by the gradual absorption into the kingdom of heaven of the Gentiles, through conversion. The end of Gentile political supremacy over the Jew and over the earth is sudden, catastrophic, destructive (Daniel ii:34, 35; vii:9-11; Rev. xix:ii-2i; 1 Thess. v:2, 3; 2 Thess. ii:3-8). Daniel, then, placed at the beginning of this long period in which we still live, writes on two great themes: First, he tells, prophetically, the whole course and end of the times of the Gentiles, i. e., the present civilization; and, secondly, he enters into minute details concerning the events in which Gentiledom ends, especially as those events bear upon the Jews. Putting ourselves, then, at Daniel's viewpoint, it is not difficult to see that the heart of this lesson is to be found in that explanation of Elohim's disciplinary dealing with Nebuchadnezzar, the first of the Gentile World-Kings, which we have in verses 18-21. At the very threshold of an epoch which, as He Knew, would be of long continuance, and frought with events and consequences of cosmic significance, He impressively taught that "the most high God ruleth in the kingdom of men, and that He appointeth over it whomsoever He will." It is a lesson long since forgotten by the Gentile civilizations. Even we boast of our government that it is "of the people, by the people, and for the people," and the name of God does not appear in the Constitution. This, doubtless, is better than that monstrous perversion of Daniel's doctrine which was called "the divine right of kings," and under which Gentile kings shamelessly subjected the people, and especially the Jewish people, to awful tyranny, but it is none the less a setting aside of Daniel's doctrine. And yet, there have been some in all the ages of Gentile supremacy who, taught of God through His prophet Daniel, have perceived that the only true philosophy of history is to be found, not indeed in the divine right of rulers, but in their divine responsibility. Nations are creatures of time, not of eternity, and therefore the divine judgments fall upon nations now, and are not postponed to eternity. Nations have arisen during the times of the Gentiles, have come to great power, have abused that power and have passed away, or have been swallowed up in other powers. Every such national extinction is but another instance of the putting forth of the unseen Hand which branded Belshazzar's wall with the sentence of doom.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD