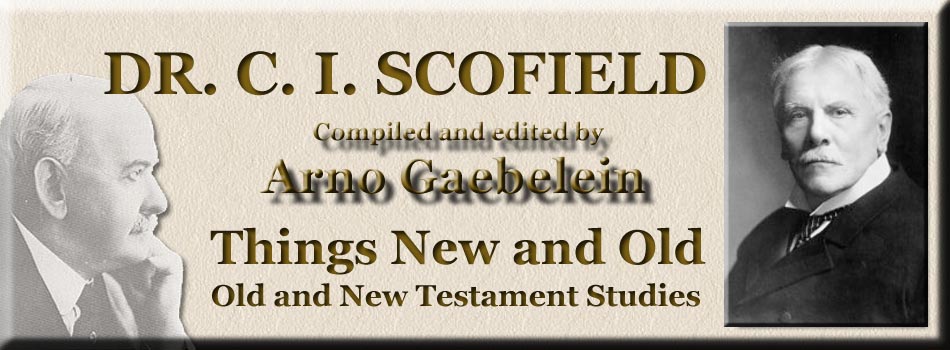

Things New and Old

By Cyrus Ingerson Scofield

Compiled and Edited By Arno Clement Gaebelein

BEFORE PILATE.(John xviii:28-40.) I. The Analysis. The present lesson does not fall into analytical form. The teaching points are to be drawn from the mutual questions and answers of Christ and of Pilate. The great lessons are:(1) the nature of Christ's kingdom in this world, but not of it; (2) the true royalty identification with the truth; (3) a lesson on substitution, Christ and Barabbas. II. The Heart of the Lesson. The full significance of the lesson topic is only to be comprehended by one who studies the parallel accounts of the appearances of Christ before the Roman governor. With the whole scene and all the events thus before us we may ask what is the deepest heart of it all. Why was a man with all the power of Rome back of him, a man who had not hesitated to send soldiers into the very temple to mingle the blood of the worshippers with their sacrifices, of a sudden grown afraid of the sanhedrin? Why should a man with absolute power, as he himself boasted, over life and death, send a man whom he confessed to be innocent to a cruel death? Our interest in a right answer to these questions is not a mere historical interest. Pilate was a typical man. As he reasoned so men, consciously or unconsciously, reason today. The underlying motives which perverted his actions pervert the actions of man now. Jesus Christ is always on trial. Physical death, indeed. He suffered but once; but millions are every day crucifying the Son of God afresh and putting Him to an open shame. Some one has said that in the deep inner sense it was Pilate who was |on trial that fateful day. In truth both Pilate and Jesus Christ were on trial; Jesus for the moment; Pilate for all time and all eternity. The Roman governor had his assize that day. The future judgment will be but declarative of the issues determined when he rejected Jesus, and released Barabbas. Of whom, then, is Pilate a type? First of all of the man who has either sadly or cynically given up the search for truth. When Jesus said: "For this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth"; Pilate's contemptuous rejoinder was, 'What is truth?" The heathen weariness was upon him. Pagan learning and philosophy were both bankrupt. Practical men, men of affairs, had ceased to concern themselves with the barren controversies of Stoic and Epicurean. Nothing came of it. Millions of modern men, more or less articulately, stand just there now in respect of religious truth—nay, in respect of the insistent personal claims of Christ. *We do not know," they say. "Some of you who profess His name say that He is but the best of men others of you do not say that quite so bluntly, but you reduce Him with your kenotic theories, and what not, within limits which after all are practically those of mere humanity. Our mothers worshipped Him—they were good and happy—we are neither good nor happy." And, next, Pilate stands for the man of expediency. "What is popular?" not "What is right; what is true?" The most contemptible possible attitude of the human soul is the attitude of the opportunist. Day by day the man who allows in himself that posture of his inner man is contracting the mean deformity of soul-stoop. The Duchess in the play, seeing her husband fawning upon the Borgia, asks, "And did I indeed marry a man with so pliant a back?" Doubtless there is a sense of what is prudent which is not ignoble. There is a noble fear—the fear of the Lord. It is one of the Gospel motives. But that other thing; that mean and politic attitude which considers the interest of the moment—that man must not think to obtain anything from the Lord. But the Lord demands all, and unquestioningly. And, again, Pilate stands for the man in whom the spiritual faculty is all but extinguished by the habit of unbelief. Before him stood the Truth, and he had Hed to his soul so long that he could not discern Him. Two things quench the flame of the spirit of man, that sense of the divine which makes the Psalmist call the human spirit, "The candle of the Lord"; the giving over of all the powers to the things of the world and the habit of skepticism. "Art thou a king?" said Pilate. "Thou sayest"; which is idiomatic for an affirmation with a reserve. "I am a king; but not in your crass sense. You think of a kingdom of force; my kingdom is the reign of faith and love. But the very suggestion that there could be some nobler, sweeter kingdom than that resting upon blood and oppression, did not even stir a question in Pilate's dead soul.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD