The Expositor's Bible

First Kings

Rev. F.W. Farrar D.D., F.R.S.

Book IV - AHAB AND ELIJAH

B.C. 877-855.

Chapter 33

KING AHAB AND QUEEN JEZEBEL.

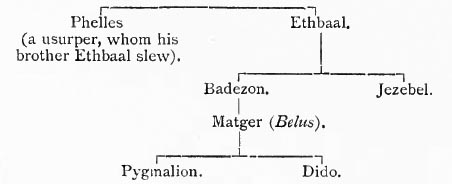

1 Kings xvi. 29-34. Omri was succeeded by his son Ahab, whose eventful reign of upwards of twenty years [589] occupies so large a space even in these fragmentary records. His name means "brother-father," and has probably some sacred reference. He is stigmatised by the historians as a king more wicked than his father, though Omri had "done worse than all who were before him.". That he was a brave warrior, and showed some great qualities during a long and on the whole prosperous career; that he built cities, and added to Israel yet another royal residence; that he advanced the wealth and prosperity of his subjects; that he was highly successful in some of his wars against Syria, and died in battle against those dangerous enemies of his country; that he maintained unbroken, and strengthened by yet closer affinity, the recent alliance with the Southern Kingdom,--all this goes for nothing with the prophetic annalists. They have no word of eulogy for the king who added Baal-worship to the sin of Jeroboam. The prominence of Ahab in their record is only due to the fact that he came into dreadful collision with the prophetic order, and with Elijah, the greatest prophet who had yet arisen. The glory and the sins of the warrior-king interested the young prophets of the schools solely because they were interwoven with the grand and sombre traditions of their mightiest reformer. The historian traces all his ignominy and ruin to a disastrous alliance. The kings of Judah had followed the bad example of David and had been polygamists. Up to this time the kings of Israel seem to have been contented with a single wife. The wealth and power of Ahab led him to adopt the costly luxury of a harem, and he had seventy sons. [590] This, however, would have been regarded in those days as a venial offence, or as no offence at all; but just as the growing power of Solomon had been enhanced by marriage with a princess of Egypt, so Ahab was now of sufficient importance to wed a daughter of the King of Tyre. "As though it had been a light thing for him to walk in the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, he took to wife Jezebel, the daughter of Ethbaal, King of the Zidonians." It was an act of policy in which religious considerations went for nothing. There is little doubt that it flattered his pride and the pride of his people, and that Jezebel brought riches with her and pomp and the prestige of luxurious royalty. [591] The Phoenicians were of the old race of Canaan, with whom all affinity was so strongly forbidden. Ethbaal--more accurately, perhaps, Itto-baal (Baal is with him) [592] --though he ruled all Phoenicia, both Tyre and Sidon, was a usurper, and had been the high priest of the great Temple of Ashtoreth in Tyre. Hiram, the friend of Solomon, had now been dead for half a century. The last king of his dynasty was the fratricide Phelles, whom in his turn his brother Ethbaal slew. He reigned for thirty-two years, and founded a dynasty which lasted for sixty-two years more. He was the seventh successor to the throne of Tyre in the fifty years which had elapsed since the death of Hiram. Menander of Ephesus, as quoted by Josephus, shows us that in the history of this family we find an interesting point of contact between sacred and classic history. Jezebel was the aunt of Virgil's Belus, and great-aunt of Pygmalion, and of Dido, the famous foundress of Carthage. [593] A king named after Baal, and who had named his daughter after Baal--a king whose descendants down to Maherbal and Hasdrubal and Hannibal bore the name of the Sun-god [594] --a king who had himself been at the head of the cult of Ashtoreth, the female deity who was worshipped with Baal--was not likely to rest content until he had founded the worship of his god in the realm of his son-in-law. Ahab, we are told, "went and served Baal and worshipped him." We must discount by recorded facts the impression which might primÔ facie be left by these sweeping denunciations. It is certain that to his death Ahab continued to recognise Jehovah. He enshrined the name of Jehovah in the names of his children. [595] He consulted the prophets of Jehovah, and his continuance of the calf-worship met with no recorded reproof from the many true prophets who were active during his reign. The worship of Baal was due to nothing more than the unwise eclecticism which had induced Solomon to establish the Bamoth to heathen deities on the mount of offence. It is exceedingly probable that the permission of Baal-worship had been one of the articles of the treaty between Tyre and Israel, which, as we know from Amos, had been made at this time. It had probably been the condition on which the fanatical Phoenician usurper had conceded to his far less powerful neighbour the hand of his daughter. It was, as we see, alike in sacred and secular history a time of treaties. The menacing spectre of Assyria was beginning to terrify the nations. Hamath, Syria, and the Hittites had formed a league of defence against the northern power, and similar motives induced the kings of Israel to seek alliance with Phoenicia. Perhaps neither Omri nor Ahab grasped all the consequences of their concession to the Sidonian princess. [596] But such compacts were against the very essence of the religion of Israel, which was "Yahveh Israel's God, and Israel Yahveh's people." The new queen inherited the fanaticism as she inherited the ferocity of her father. She acquired from the first a paramount sway over the weak and uxorious mind of her husband. Under her influence Ahab built in Samaria a splendid temple and altar to Baal, in which no less than four hundred orgiastic priests served the Phoenician idol in splendid vestments, and with the same pompous ritual as in the shrines at Tyre. In front of this temple, to the disgust and horror of all faithful worshippers of Jehovah, stood an Asherah in honour of the Nature-goddess, and Matstseboth pillars or obelisks which represented either sunbeams or the reproductive powers of nature. In these ways Ahab "did more to provoke the Lord God to anger than all the kings of Israel that were before him." [597] When we learn what Baal was, and how he was worshipped, we are not surprised at so stern a condemnation. Half Sun-god, half Bacchus, half Hercules, Baal was worshipped under the image of a bull, "the symbol of the male power of generation." In the wantonness of his rites he was akin to Peor; in their cruel atrocity to the kindred Moloch; in the demand for victims to be sacrificed to the horrible consecration of lust and blood he resembled the Minotaur, the wallowing "infamy of Crete," with its yearly tribute of youths and maidens. What the combined worship of Baal and Asherah was like--and by Jezebel with Ahab's connivance they were now countenanced in Samaria--we may learn from the description of their temple at Apheka. [598] It confirms what we are incidentally told of Jezebel's devotions. It abounded in wealthy gifts, and its multitude of priests, women, and mutilated ministers--of whom Lucian counted three hundred at one sacrifice--were clad in splendid vestments. Children were sacrificed by being put in a leathern bag and flung down from the top of the temple, with the shocking expression that "they were calves, not children." In the forecourt stood two gigantic phalli. The Galli were maddened into a tumult of excitement by the uproar of drums, shrill pipes, and clanging cymbals, gashed themselves with knives and potsherds, and often ran through the city in women's dress. [599] Such was the new worship with which the dark murderess insulted the faith in Jehovah. Could any condemnation be too stern for the folly and faithlessness of the king who sanctioned it? A consequence of this tolerance of polluted forms of worship seems to have shown itself in defiant contempt for sacred traditions. At any rate, it is in this connexion that we are told how Hiel of Bethel set at naught an ancient curse. After the fall of Jericho Joshua had pronounced a curse upon the site of the city. It was never to be rebuilt, but to remain under the ban of God. The site, indeed, had not been absolutely uninhabited, for its importance near the fords of Jordan necessitated the existence of some sort of caravanserai in or near the spot. [600] At this time it belonged to the kingdom of Israel, though it was in the district of Benjamin and afterwards reverted to Judah. [601] Hiel, struck by the opportunities afforded by its position, laughed the old cherem to scorn, and determined to rebuild Jericho into a fortified and important city. But men remarked with a shudder that the curse had not been uttered in vain. The laying of the foundation was marked by the death of his firstborn Abiram, the completion of the gates by the death of Segub, his youngest son. [602] The shadow of Queen Jezebel falls dark for many years over the history of Israel and Judah. She was one of those masterful, indomitable, implacable women who, when fate places them in exalted power, leave a terrible mark on the annals of nations. What the Empress Irene was in the history of Constantinople, or the "She-wolf of France" in that of England, or Catherine de Medicis in that of France, that Jezebel was in the history of Palestine. The unhappy Juana of Spain left a physical trace upon her descendants in the perpetuation of the huge jaw which had gained her the soubriquet of Maultasch; but the trace left by Jezebel was marked in blood in the fortunes of the children born to her. Already three of the six kings of Israel had been murdered, or had come to evil ends; but the fate of Ahab and his house was most disastrous of all, and it became so through the "whoredoms and witchcrafts" of his Sidonian wife. A thousand years later the name of Jezebel was still ominous as that of one who seduced others into fornication and idolatry. [603] If no king so completely "sold himself to work wickedness" as Ahab, it was because "Jezebel his wife stirred him up." [604] Yet, however guilty may have been the uxorious apostasies of Ahab, he can hardly be held to be responsible for the marriage itself. The dates and ages recorded for us show decisively that the alliance must have been negotiated by Omri, for it took place in his reign and when Ahab was too young to have much voice in the administration of the kingdom. He is only responsible for abdicating his proper authority over Jezebel, and for permitting her a free hand in the corruption of worship, while he gave himself up to his schemes of worldly aggrandisement. Absorbed in the strengthening of his cities and the embellishment of his ivory palaces, he became neglectful of the worship of Jehovah, and careless of the more solemn and sacred duties of a theocratic king. The temple to Baal at Samaria was built; the hateful Asherah in front of it offended the eyes of all whose hearts abhorred an impure idolatry. Its priests and the priests of Astarte were the favourites of the court. Eight hundred and fifty of them fed in splendour at Jezebel's table, and the pomp of their sensuous cult threw wholly into the shade the worship of the God of Israel. Hitherto there had been no protest against, no interference with the course of evil. It had been suffered to reach its meridian unchecked, and it seemed only a question of time that the service of Jehovah would yield to that of Baal, to whose favour the queen probably believed that her priestly father had owed his throne. There are indications that Jezebel had gone further still, and that Ahab, however much he may secretly have disapproved, had not interfered to prevent her. For although we do not know the exact period at which Jezebel began to exercise violence against the worshippers of Jehovah, it is certain that she did so. This crime took place before the great famine which was appointed for its punishment, and which roused from cowardly torpor the supine conscience of the king and of the nation. Jezebel stands out on the page of sacred history as the first supporter of religious persecution. We learn from incidental notices that, not content with insulting the religion of the nation by the burdensome magnificence of her idolatrous establishments, she made an attempt to crush Jehovah-worship altogether. Such fanaticism is a frequent concomitant of guilt. She is the authentic authoress of priestly inquisitions. The Borgian monster, Pope Alexander VI., who founded the Spanish Inquisition, is the lineal inheritor of the traditions of Jezebel. Had Ahab done no more than Solomon had done in Judah, the followers of the true faith in Israel would have been as deeply offended as those of the Southern Kingdom. They would have hated a toleration which they regarded as wicked, because it involved moral corruption as well as the danger of national apostasy. Their feelings would have been even more wrathful than were stirred in the hearts of English Puritans when they heard of the Masses in the chapel of Henrietta Maria, or saw Father Petre gliding about the corridors of Whitehall. But their opposition was crushed with a hand of iron. Jezebel, strong in her entourage of no less than eight hundred and fifty priests, to say nothing of her other attendants, audaciously broke down the altars of Jehovah--even the lonely one on Mount Carmel--and endeavoured so completely to extirpate all the prophets of Jehovah that Elijah regarded himself as the sole prophet that was left. Those who escaped her fury had to wander about in destitution, and to hide in dens and caves of the earth. The apostasy of Churches always creeps on apace, when priests and prophets, afraid of malediction, and afraid of imperilling their worldly interests become cowards, opportunists, and time-servers, and not daring to speak out the truth that is in them, suffer the cause of spirituality and righteousness to go by default. But "when Iniquity hath played her part, Vengeance, leaps upon the stage. The comedy is short, but the tragedy is long. The black guard shall attend upon you: you shall eat at the table of sorrow, and the crown of death shall be upon your heads, many glittering faces looking upon you." [605]

|

|

|

|

|

[589] It is needless in each separate case to enter into the chronological minutiŠ about which the historian is little solicitous. A table of the chronology so far as it can be ascertained is furnished, infra. [590] 1 Kings xx. 5; 2 Kings x. 7. [591] Hitzig thinks that Psalm xlv. was an epithalamium on this occasion, from the mention of "ivory palaces" and "the daughter of Tyre." Had it been composed for the marriage of Solomon, or Jehoram and Athaliah, or any king of Judah, there would surely have been an allusion to Jerusalem. Moreover, the queen is called שֵׁנׇל, which is a Chaldee (Dan. v. 2), or perhaps a North Palestine word. The word in Judah was Gebira. [592] Ἰθόβαλος, Josephus, Antt., VIII. xiii. 1; c. Ap., I. 18 (quoting the heathen historian Menander of Ephesus). It may, however, be "Man of Baal," like Saul's son Ishbaal (Ishbosheth). In Tyre the high priest was only second to the king in power (Justin, Hist., xviii. 4), and Ethbaal united both dignities. He died aged sixty-eight. Another Ethbaal was on the throne during the siege of Tyre by Nebuchadnezzar (Josephus, Antt., X. xi. I). [593] Josephus, c. Ap., I. 18. The genealogy is:--

See Canon Rawlinson, Speaker's Commentary, ad loc. [594] Plaut., PŠnul., V. ii. 6, 7. Phoenician names abound in the element "Baal." [595] Ahaziah ("Jehovah supports"), Jehoram ("Jehovah is exalted"), Athaliah (?). The word Baal merely meant "Lord"; and perhaps the fact that at one time it had been freely applied to Jehovah Himself may have helped to confuse the religious perceptions of the people. Saul, certainly no idolater, called his son Eshbaal ("the man of Baal"); and it was only the hatred of the name Baal in later times which led the Jews to alter Baal into Bosheth ("shame"), as in Ishbosheth, Mephibosheth. David himself had a son named Beeliada ("known to Baal"), which was altered into Eliada (1 Chron. xiv. 7, iii. 8; 2 Sam. v. 16; comp. 2 Chron. xvii. 17). We even find the name Bealiah ("Baal is Jah") as one of David's men (1 Chron. xii. 5). Hoshea too records that Baali ("my Lord") was used of Jehovah, but changed into Ishi ("my husband") (Hosea ii. 16, 17). It is used simply for owner ("the baal of an ox") in "the Book of the Covenant" (Exod. xxi. 28). See Robertson Smith, Rel. of the Semites, 92. [596] Ethbaal is called King of Sidon (1 Kings xvi. 31), and was also King of Tyre (Menander ap. Josephus, Antt., VIII. xiii. 1). [597] 1 Kings xvi. 23; 2 Kings iii. 2, x. 27. [598] Asherim seem to be upright wooden stocks of trees in honour of the Nature-goddess Asheroth. The Temple of Baal at Tyre had no image, only two Matstseboth, one of gold given by Hiram, one of "emerald" (Dius and Menander ap. Josephus, Antt., VIII. v. 3; c. Ap., I. 18; Herod., ii. 66). [599] D÷llinger, Judenth. u. Heidenthum (E. T.), i. 425-29. [600] 2 Sam. x. 5; Judg. iii. 28. [601] 2 Chron. xxviii. 15. [602] Comp. Josh. vi. 26; 2 Sam. x. 5. [603] Rev. ii. 20. [604] 1 Kings xxi. 25, 26. [605] Henry Smith, The Trumpet of the Lord sounding to Judgment. |

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD