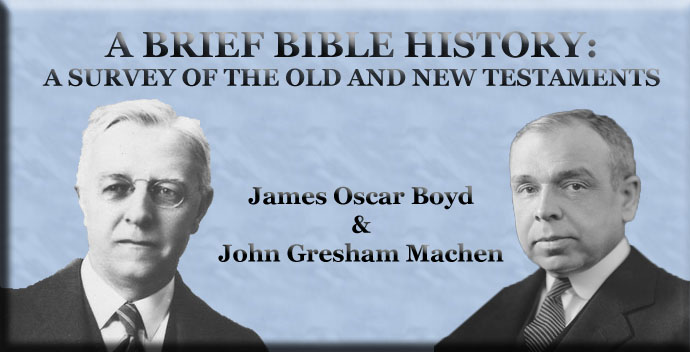

A Brief Bible History:

A Survey of the Old and New Testaments

By James Oscar Boyd & John Gresham Machen

Section I - Lesson IX

The Kingdom of IsraelI Kings, Chapter 12 to II Kings, Chapter 17With the death of Solomon came the lasting division of the tribes into two kingdoms, a northern and a southern, known as the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. Rehoboam on his accession announced a policy of repression and even oppression that alienated completely the loyalty of Ephraim and the other northern tribes, which were never attached to the house of David in the same way as the tribe of Judah was. Under a man of Ephraim, therefore, Jeroboam the son of Nebat, who in earlier years had challenged even Solomon's title, the ten tribes revolted from Rehoboam and established a separate state. Rehoboam found himself too weak to prevent this secession, and he and his descendants of David's dynasty had to content themselves with the narrow boundaries of Judah. To be sure, in Jerusalem they possessed the authorized center of public worship for the whole nation. It was to offset this advantage that Jeroboam made Bethel, that spot associated in the minds of the people with the patriarchs themselves, his religious capital. And, influenced perhaps by the Egyptian example of steer worship (for he had long lived as a fugitive in Egypt in Solomon's reign), he made golden steers and placed them in the sanctuary at Bethel and in that at Dan in the extreme north. (See close of Lesson VI.) To these places and under these visible symbols of brute force, Jeroboam summoned his people to worship Jehovah. It was the old national religion but in the degraded form of an image worship forbidden by the Mosaic Commandments. A throne thus built on mere expediency could not endure. Jeroboam's son was murdered after a two years' reign. Nor did this usurper succeed in holding the throne for his house any longer than Jeroboam's house had lasted. At length Omri, commander of the army, succeeded in founding a dynasty that furnished four kings. Ahab, son of Omri, who held the throne the longest of these four, is the king with whom we become best acquainted of all the northern monarchs. This is partly because of the relations between Ahab and Elijah the prophet. Ahab's name is also linked with that of his queen, the notorious Jezebel, a princess of Tyre, who introduced the worship of the Tyrian Baal into Israel and even persecuted all who adhered to the national religion. This alliance with Tyre, and the marriage of Ahab's daughter to a prince of Judah, secured Israel on the north and the south, and left Ahab free to pursue his father's strong policy toward the peoples to the east, Moab and Syria. Upon Ahab's death in battle against Syria, Moab revolted, and the two sons of Ahab, in spite of help from the house of David in Jerusalem, were unable to stave off the ruin that threatened the house of Omri. Jehu, supported by the army in which he was a popular leader, seized the throne, with the usual assassination of all akin to the royal family. His inspiration to revolt had been due to Jehovah's prophets, and his program was the overthrow of Baal worship in favor of the old national religion. Though Jehu thoroughly destroyed the followers of Jezebel's foreign gods, he and his sons after him continued to foster the idolatrous shrines at Bethel and Dan, so that the verdict of the sacred writer upon them is unfavorable: they "departed not from all the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, wherewith he made Israel to sin." Mesha, king of Moab, II Kings 3:4, lived long enough to see his oppressors, the kings of Omri's house, overthrown and the land of Israel reduced to great weakness. (See article "Moabite Stone" in any Bible dictionary.) Jehu's son, Jehoahaz, witnessed the deepest humiliation of Israel at the hands of Syria. But it was not many years after Mesha's boasting that affairs took a complete turn. Jehu's grandson, Jehoash, spurred by Elisha the prophet even on his deathbed, began the recovery which attained its zenith in the reign of Jeroboam II, fourth king of Jehu's line. Though little is told of this reign in the Book of Kings, it is clear that at no time since Solomon's reign had a king of Israel ruled over so large a territory. It was the last burst of glory before total extinction. There is a history lying between the reigns of Jeroboam I, founder of the Northern Kingdom, and of Jeroboam II, its last prosperous monarch, which has scarcely been referred to in this brief sketch of its kings. It is the history of Jehovah's prophets. Hosea; Amos; JonahReference has already been made to the rise of the prophetic order as such, in the time of Samuel. (Lesson VII.) With each crisis in the affairs of the nation God raised up some notable messenger with a word from him to the people or to the ruler. But all along the fire of devotion to God and country was kept alive by humbler, unnamed men, who supplied a sound nucleus of believers even to this Northern Kingdom with its idolatrous shrines and its usurping princes. I Kings 18:4; 19:18. The greatest names are those of Elijah and Elisha. The earlier struggle to keep Israel true to Jehovah focuses in these two men, one the worthy successor of the other. Their time marked perhaps the lowest ebb of true religion in all the history of God's Kingdom on earth. It is no wonder, therefore, that such stern, strong men were not only raised up to fight for the God of Moses and Samuel and David, but also endowed with exceptional powers, to work wonders and signs for the encouragement of the faithful and the confounding of idolators and sinners. Such was the purpose of their notable miracles. Elijah and Elisha wrote nothing. But in their spirit rose up Hosea and Amos a century later — men who have left a record of their prophecies in the books that bear their names. Denunciation of sin, especially in the higher classes, announcement of impending punishment for that sin, and promise of a glorious, if distant, future of pardon, peace, and prosperity through God's grace and man's sincere repentance — these things form the substance of their eloquent messages. Hosea is noteworthy for his striking parable of a patient husband and a faithless wife to illustrate God's love and Israel's infidelity. Amos, himself a herdsman from Judah sent north to denounce a king and people not his own, is startling in the suddenness with which he turns the popular religious ideas against those who harbor them. See, for example, ch. 3:2, where Amos makes the unique relation between Jehovah and Israel the reason, not for Israel's safety from Jehovah's wrath, as the people thought, but for the absolute certainty of Israel's punishment for all its sins. These two prophets, the last of the Northern Kingdom, had the melancholy duty of predicting the utter overthrow of what the first Jeroboam had set up in rebellion and sin two centuries before.

|

|

|

|

QUESTIONS ON LESSON IX1. When, why, and under whose lead did the ten tribes break away from the house of David? 2. Outline the fortunes of the kings of Israel from Jeroboam I to Jeroboam II. 3. Who were the outstanding prophets in the Northern Kingdom, and what was the substance of their messages?

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD