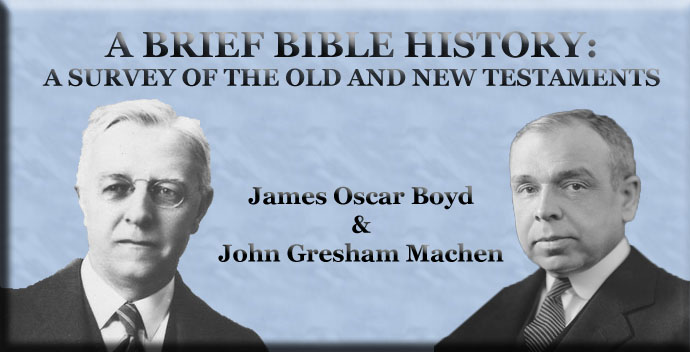

A Brief Bible History:

A Survey of the Old and New Testaments

By James Oscar Boyd & John Gresham Machen

Section I - Lesson XIII

The Jewish State Under PersiaEzra, Chapters 3 to 10; Esther; Nehemiah; Haggai; Zechariah; MalachiFor two centuries Judea, like the rest of western Asia, was under the domination of the Persians, whose great royal names, Cyrus, Darius, Xerxes, Artaxerxes, are familiar to every student of history. The Old Testament spans one of those two centuries of Persian rule, 539-430, while for the other century, 430-332, we are dependent for the little we know about the Jews upon some documents recently discovered in Egypt, an occasional notice in classical historians, and the brief narrative of Josephus, the Jewish historian of the first Christian century. Even in the century covered by the books of the Bible there are long stretches of silence separating periods that are fairly reported. First comes the time of Zerubbabel and Jeshua, the leaders, civil and religious, under whom the Jews returned and erected the Temple. This story carries us, though with a seventeen-year gap in its midst, from 538, the year after Cyrus took Babylon, to 515, the sixth year of Darius the Great, and is recorded in the first six chapters of the book of Ezra. To help us in understanding this time we have also the prophecies of Haggai and Zechariah, though the last six chapters of Zechariah belong to another age. After the completion of the new Temple the curtain falls on Judea and, save for a single verse, Ezra 4:6, we hear no more of it for fifty-seven years. However, the interesting story of Esther belongs in these years, for the Ahasuerus of the Bible is the Xerxes of Greek history — that vain, fickle, and voluptuous monarch who was beaten at Salamis and Plataea. The Jews must have been a part of the vast host with which he crossed from Asia to Europe. But the drama unfolded in the book of Esther was played far from Palestine, at Susa, the Persian capital. With the seventh year of the next reign — that of Artaxerxes I — the curtain rises again on Judea, as we accompany thither the little band of Jews whom Ezra, the priestly "scribe," brought back with him from Babylonia to Jerusalem. This account is found in the last four chapters of the book of Ezra, most of it in the form of personal reminiscences covering less than one year. The curtain falls again abruptly at the end of Ezra's memoirs, and rises as abruptly on Nehemiah's memoirs at the beginning of the book which bears his name. But there is every reason to believe that the letters exchanged between the Samaritans and the Persian court, preserved in the fourth chapter of Ezra, belong to this interval of thirteen years between the two books of Ezra and Nehemiah. For this alone can explain two riddles: first, who are "the men that came up from thee unto Jerusalem," Ezra 4:12, if they are not Ezra and his company, ch. 7? And second, what else could explain the desolate condition of Jerusalem and Nehemiah's emotion on learning of it, Neh. 1:3, if not the mischief wrought by the Jews' enemies when "they went in haste to Jerusalem," armed with a royal injunction, and "made them to cease by force and power"? Ezra 4:23. Some persons are inclined to date the prophet Malachi at just this time also, shortly before Nehemiah's arrival. But it is probably better to place the ministry of this last of the Old Testament prophets at the end of Nehemiah's administration. Nehemiah's points of contact with Malachi are most numerous in his last chapter, ch. 13, in which he writes of his later visit to Jerusalem. Compare Neh. 13:6 with ch. 1:1. In Cyrus' reign the great Return was followed immediately by the erection of an altar and the resumption of sacrifice. Preparations for rebuilding the Temple, however, and even the laying of the corner stone, proved a vain beginning, as the Samaritans, jealous of the newcomers and angered by their own rebuff as fellow worshipers with the Jews, succeeded in hindering the prosecution of the work for many years. Ezra 3:1 to 4:5. It was not until the second year of Darius' reign, 520, nearly two decades later, that the little community, spurred out of their selfishness and lethargy by Haggai and Zechariah, arose and completed the new Temple, in the face of local opposition but with royal support. Ch. 4:24 to 6:15. Fifty-seven years later, in the seventh year of Artaxerxes, 458, came Ezra with some fifteen hundred men, large treasures, and sweeping privileges confirmed by a royal edict, the text of which he has preserved in the seventh chapter of his book. He was given the king's support in introducing the Law of God as the law of the land, binding upon all its inhabitants, whom he was to teach its contents and punish for infractions of it. How Ezra used his exceptional powers in carrying out the reform he judged most needed — the dissolution of mixed marriages between Jew and Gentile forbidden by the Law — is told in detail in his own vivid language in chs. 9, 10. It helps us to understand Malachi's zeal in this same matter. Mai. 2:11. And the difficulty of this reform appears also from Nehemiah's memoirs, since the same abuse persisted twenty-five years after Ezra fought it. Neh. 13:23-27. After the failure to fortify Jerusalem recorded in Ezra 4:8-23, Nehemiah, a Jew in high station and favor at Artaxerxes' court, obtained from his king a personal letter, appointing him governor of Judea for a limited time, with the special commission to rebuild the walls and gates of Jerusalem. The same bitter hostility which the Samaritans and other neighbors in Palestine throughout had shown toward the returned Jews, reached its climax in the efforts of Sanballat and others in public and private station to hinder Nehemiah's purpose. But with great energy and bravery, and with a personal appeal and example that swept all into the common stream of patriotic service, Nehemiah built the ruined walls and gates in fifty-two days, instituted social reforms, ch. 5, and imposed a covenant on all the people to obey the Law which Ezra read and expounded. Chs. 8 to 10. Elements in the little nation that joined with his enemies to discredit and even to assassinate him were banished or curbed. The origin of the peculiar sect of the Samaritan is connected with Nehemiah through his rigor in banishing a grandson of the high priest who had married Sanballat' s daughter. This disloyalty of the priesthood is also one of Malachi's chief indictments against his nation, and the basis of his promise that a great reformer, an "Elijah," should arise to prepare the sinful people for the coming of their God.

|

|

|

|

QUESTIONS ON LESSON XIII1. How long after the Return was the Temple finished? Who hindered? Who helped? 2. What are the scene and the date of the book of Esther? 3. Compare the return of the Jews to Jerusalem under Ezra with that under Zerubbabel (a) in date, (b) in numbers, (c) in purpose and result. 4. Tell the story of Nehemiah: the occasion of his return, his enemies, his achievements. In what did Ezra help him? 5. Associate the ministry of the three prophets of this period after the Exile with the leaders and movements they respectively helped.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD