|

THE MOABITE STONE AND THE

INSCRIPTION OF SILOAM.

The alphabet of Egyptian

origin. — Discovery of the

Moabite Stone. — Translation

of the inscription. — Points

of interest raised by the

inscription. — Discovery of

the Siloam inscription.—The

translation. — The date, —

Its bearing upon the

topography of Jerusalem.

Modern discovery

has as yet thrown little

contemporary light on the period

of Israelitish history which

extends from the conquest of

Canaan to the time when the

kingdom of David was rent into

the two monarchies of Israel and

Judah. The buried ruins of

Phœnicia have not yet been

explored, and we have still to

depend on the statements of

classical writers for what we

know, outside the Bible records,

of Hiram the Tyrian king, the

friend of David and Solomon. It

is certain, however, that state

archives already existed in the

chief cities of Phœnicia, and a

library was probably attached to

the ancient temple of Baal, the

Sun-god, at Tyre, which was

restored by Hiram. It was from

the Phœnicians that the

Israelites, and the nations

round about them, received their

alphabet. This alphabet was of

Egyptian origin. As far back as

the monuments of Egypt carry us,

we find the Egyptians using

their hieroglyphics to express

not only ideas and syllables,

but also the letters of an

alphabet. Even in the remote

epoch of the second dynasty they

already possessed an alphabet in

which the twenty-one simple

sounds of the language were

represented by special

hieroglyphic pictures. Such

hieroglyphic pictures,

however, were employed only on

the public monuments; for books

and letters and business

transactions the Egyptians made

use of a running hand, in which

the original pictures had

undergone great transformations.

This running hand is termed “hieratic,” and

it was from the hieratic forms

of the Egyptian letters that the

Phœnician letters were derived.

We have already

seen that the coast of the Delta

was so thickly peopled with

Phœnician settlers as to have

acquired the name of Keft-ur, or

Caphtor, “greater

Phœnicia;” and

these settlers it must have been

who first borrowed the alphabet

of their Egyptian neighbours.

For purposes of trade they must

have needed some kind of

writing, by means of which they

could communicate with the

natives of the country, and

their business-like instincts

led them to adopt only the

alphabet used by the latter, and

to discard all the cumbrous

machinery of ideographs and

syllabic characters by which it

was accompanied. It was

doubtless in the time of the

Hyksos that the Egyptian

alphabet became Phœnician. From

the Delta it was handed on to

the mother country of Phœnicia,

and there the letters received

new names, derived from objects

to which they bore a resemblance

and which began with the sounds

they represented. These names,

as well as the characters to

which they belonged, have

descended to ourselves, for the

Phœnician alphabet passed first

from the Phœnicians to the

Greeks, then from the Greeks to

the Romans, and finally from the

Romans to the nations of modern

Europe. The very word alphabet is

a living memorial of the fact,

since it is composed of alpha and beta,

the Greek names of the two first

letters, and these names are

simply the Phœnician aleph, “an

ox,” and beth, “a

house.” Just

as in our own nursery

days it was imagined that we

should remember our lessons

better if we were taught that “A

was an Archer who shot at a

frog,” so

the forms of the letters were

impressed on the memory of the

Phœnician boys by being likened

to the head of an ox or the

outline of a house.

But before the

alphabet was communicated to

Greece by the Phœnician traders,

it had already been adopted by

their Semitic kinsmen in Western

Asia. Excavations in Palestine

and the country east of the

Jordan would doubtless bring to

light inscriptions compiled in

it much older than the oldest

which we at present know. Only a

few years ago the gap between

the time when the Phœnicians

first borrowed their new

alphabet and the time to which

the earliest texts written in it

belonged was very great indeed.

But during the last fifteen

years two discoveries have been

made which help to fill it up,

and prove to us at the same time

what may be found if we will

only seek.

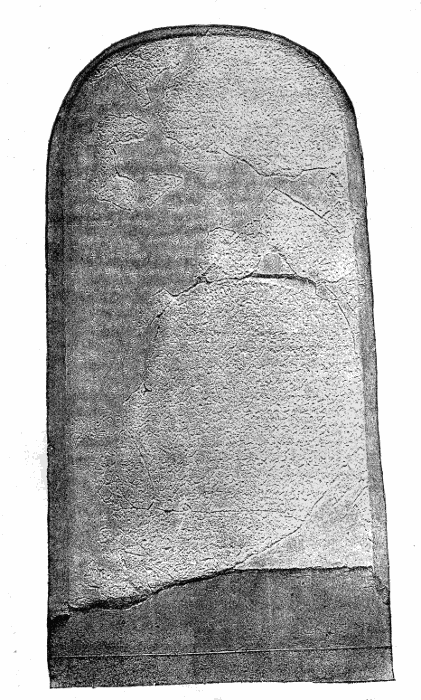

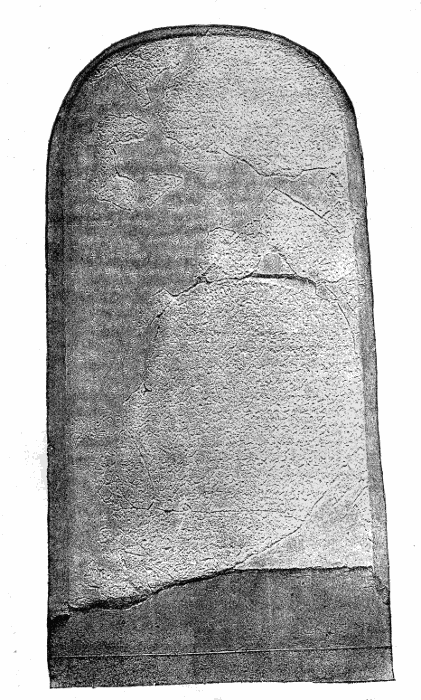

The Moabite

Stone, erected by King Mesha, at

Dibon.

One of these

discoveries is that of the

famous Moabite Stone. In the

summer of 1869, Dr. Klein, a

German missionary, while

travelling in what was once the

land of Moab, discovered a most

curious relic of antiquity among

the ruins of Dhibân, the ancient

Dibon. This relic was a stone of

black basalt, rounded at the

top, two feet broad and nearly

four feet high. Across it ran an

inscription of thirty-four lines

in the letters of the Phœnician

alphabet. Dr. Klein

unfortunately did not realise

the importance of the discovery

he had made; he contented

himself with copying a few

words, and endeavouring to

secure the monument for the

Berlin Museum. Things always

move slowly in the East, and it

was not until a year later that

the negociations for the

purchase of

the stone were completed between

the Prussian Government on the

one side and the Arabs and

Turkish pashas on the other. At

length, however, all was

arranged, and it was agreed that

the stone should be handed over

to the Germans for the sum of

£80. At this moment M. Clermont-Ganneau,

a member of the French Consulate

at Jerusalem, with lamentable

indiscretion, sent men to take

squeezes of the inscription, and

offered no less than £375 for

the stone itself. At once the

cupidity of both Arabs and

pashas was aroused; the Governor

of Nablûs demanded the treasure

for himself, while the Arabs,

fearing it might be taken from

them, put a fire under it,

poured cold water over it, broke

it in pieces, and distributed

the fragments as charms among

the different families of the

tribe. Thanks to M. Clermont-Ganneau,

most of these fragments have now

been recovered, and the stone,

once more put together, may be

seen in the Museum of the Louvre

at Paris. The fragments have

been fitted into their proper

places by the help of the

imperfect squeezes taken before

the monument was broken.

When the

inscription came to be read, it

turned out to be a record of

Mesha, king of Moab, of whom we

are told in 2 Kings iii. that

after Ahab's death he “rebelled

against the king of Israel,” and

was vainly besieged in his

capital Kirharaseth by the

combined armies of Israel, Judah

and Edom. Mesha describes the

successful issue of his revolt,

and the revenge he took upon the

Israelites for their former

oppression of his country. The

translation of the inscription

is as follows:—

“I, Mesha, am the

son of Chemosh-Gad, king of

Moab, the Dibonite. My father

reigned over Moab thirty years,

and I reigned after my father.

And I erected

this stone to Chemosh at Kirkha,

a (stone of) salvation, for he

saved me from all despoilers,

and made me see my desire upon

all my enemies, even upon Omri,

king of Israel. Now they

afflicted Moab many days, for

Chemosh was angry with his land.

His son succeeded him; and he

also said, I will afflict Moab.

In my days (Chemosh) said, (Let

us go) and I will see my desire

on him and his house, and I will

destroy Israel with an

everlasting destruction. Now

Omri took the land of Medeba,

and (the enemy) occupied it in

(his days and in) the days of

his son, forty years. And

Chemosh (had mercy) on it in my

days; and I fortified Baal-Meon,

and made therein the tank, and I

fortified Kiriathaim. For the

men of Gad dwelt in the land of

(Atar)oth from of old, and the

king (of) Israel fortified for

himself Ataroth, and I assaulted

the wall and captured it, and

killed all the warriors of the

wall for the well-pleasing of

Chemosh and Moab; and I removed

from it all the spoil, and

(offered) it before Chemosh in

Kirjath; and I placed therein

the men of Siran and the men of

Mochrath. And Chemosh said to

me, Go take Nebo against Israel.

(And I) went in the night, and I

fought against it from the break

of dawn till noon, and I took it

and slew in all seven thousand

(men, but I did not kill) the

women (and) maidens, for (I)

devoted them to Ashtar-Chemosh;

and I took from it the vessels

of Yahveh, and offered them

before Chemosh. And the king of

Israel fortified Jahaz and

occupied it, when he made war

against me; and Chemosh drove

him out before (me, and) I took

from Moab two hundred men, all

its poor, and placed them in

Jahaz, and took it to annex it

to Dibon. I built Kirkha, the

wall of the forest, and the wall

of the city, and I built the

gates thereof,

and I built the towers thereof,

and I built the palace, and I

made the prisons for the

criminals within the walls. And

there was no cistern in the wall

at Kirkha, and I said to all the

people, Make for yourselves,

every man, a cistern in his

house. And I dug the ditch for

Kirkha by means of the (captive)

men of Israel. I built Aroer,

and I made the road across the

Arnon. I built Beth-Bamoth, for

it was destroyed; I built Bezer,

for it was cut (down) by the

armed men of Dibon, for all

Dibon was now loyal; and I

reigned from Bikran, which I

added to my land, and I built

(Beth-Gamul) and Beth-Diblathaim

and Beth-Baal-Meon, and I placed

there the poor (people) of the

land. And as to Horonaim, (the

men of Edom) dwelt therein (from

of old). And Chemosh said to me,

Go down, make war against

Horonaim and take (it. And I

assaulted it, and I took it,

and) Chemosh (restored it) in my

days. Wherefore I made . .

. year . . . and I . . .

.”

The last line or

two, describing the war against

the Edomites, is unfortunately

lost beyond recovery. The rest

of the text, however, it will be

seen, is pretty perfect, and is

full of interest to Biblical

students. The whole inscription

reads like a chapter from one of

the historical books of the Old

Testament. Not only are the

phrases the same, but the words

and grammatical forms are, with

one or two exceptions, all found

in Scriptural Hebrew. We learn

that the language of Moab

differed less from that of the

Israelites than does one English

dialect from another. Perhaps

the most interesting fact

disclosed by the inscription is

that Chemosh, the national god

of the Moabites, had come to be

regarded not only as the supreme

deity, but even as almost the

only object of their worship.

Except in the passage which

alludes to the

dedication of women and maidens

to Ashtar-Chemosh, Mesha speaks

as a monotheist, and even here

the female Ashtar or Ashtoreth

is identified with the supreme

male deity Chemosh. Like the

Assyrian kings, moreover, who

ascribed their victories and

campaigns to the inspiration of

the god Assur, Mesha ascribes

his successes to the orders of

Chemosh. He uses, in fact, the

language of Scripture; as the

Lord said to David, “Go

and smite the Philistines” (1

Sam. xxiii. 2), so Chemosh is

made to say to Mesha, “Go,

take Nebo;” and

as God promised to “drive

out” the

Canaanites before Israel, so

Mesha declares that Chemosh

drove out Israel before him from

Jahaz. Mesha even sets up a

stone of salvation to Chemosh,

like Eben-ezer, “the

stone of help,” set

up by Samuel (1 Sam. vii. 12);

and the statement that Chemosh

had been “angry

with his land,” but

had made Mesha “see

his desire upon all his

enemies,” reminds

us of the well-known passages in

which the Psalmist declares

that “God

shall let me see my desire upon

mine oppressors,” and

the author of the Book of Judges

recounts how that “the

anger of the Lord was hot

against Israel.”

The covenant name

of the God of Israel itself

occurs in the inscription, spelt

in exactly the same way as in

the Old Testament. Its

occurrence is a proof, if any

were needed, that the

superstition which afterwards

prevented the Jews from

pronouncing it did not as yet

exist. The name under which God

was worshipped in Israel was

familiar to the nations round

about. Nay, more; we gather that

even after the attempt of

Jezebel to introduce the Baalim

of Sidon into the northern

kingdom, Yahveh was still

regarded as the national god,

and that the worship carried on

at the high places, idolatrous

and contrary

as it was to the law, was

nevertheless performed in His

name. The high-place of Nebo,

like so many of the other

localities mentioned in the

inscription, is also mentioned

in the prophecy against Moab

contained in Isa. xv. xvi. It is

even possible that the words of

the verse in the Book of Isaiah

in which it is named have

undergone transposition, and

that the true reading is, “He

is gone up to Dibon and to Beth-Bamoth

to weep; Moab shall howl over

Nebo and over Medeba.” The

inscription informs us that

Beth-Bamoth, “the

house of the high-places,” was

the name of a place near Dibon,

the name of which appears in the

last verse of Isaiah xv. under

the form of Dimon, the letter b being

changed by the prophet into m,

in order to connect it with the

word dâm, “blood.” Kirkha, “the

wall of the forest,” the

modern Kerak, is called Kir of

Moab and Kir-haresh or

Kir-hareseth by Isaiah, and

Kir-heres by Jeremiah, which by

a slight change of vocalisation

would signify “the

wall of the forest.” The

form Kir-haraseth is also used

in the Book of Kings.

The story told by

the Stone, and the account of

the war against Moab given in

the Bible, supplement one

another. Dr. Ginsburg has

suggested that the deliverance

of Moab from Israel was brought

about during the reign of

Ahaziah, the successor of Ahab,

and that Joram, the successor of

Ahaziah, was subsequently driven

out of Jahaz, which lay on the

southern side of the Arnon; but

that after this the tide of

fortune turned, Joram summoned

his allies from Judah and Edom,

ravaged Moab, and blockaded

Mesha in his capital of Kirkha.

Then came the sacrifice by Mesha

of his eldest son on the wall of

Kirkha—so that “there

was great indignation against

Israel,” and

the allied forces retreated

back “to

their own land.”

The Moabite Stone

shows us what were the forms of

the Phœnician letters used on

the eastern side of the Jordan

in the time of Ahab. The forms

employed in Israel and Judah on

the western side could not have

differed much; and we may

therefore see in these venerable

characters the precise mode of

writing employed by the earlier

prophets of the Old Testament.

This knowledge is of great

importance for the correction

and restoration of corrupt

passages, and more especially of

proper names, the spelling of

which has been deformed by

copyists.

Just, however, as

the writing of two persons at

the present day must differ, so

also the writing of two nations

like the Moabites and Jews must

have differed to some extent.

Moreover, there must have been

some distinction between the

more cursive writing of a

papyrus-roll and the carefully

cut letters of a public monument

like that of Mesha. Indeed, that

such a distinction did exist we

have proof in a passage (Isa.

viii. 1) which has been

mistranslated in the Authorised

Version, but which ought to be

rendered: “Take

thee a great slab, and write

upon it with the graving-tool of

the people: Hasten spoil, hurry

booty.” Here

words which were afterwards to

be made more emphatic by

becoming the name of one of

Isaiah's children, were written

in a way that all could read,

not in the running hand of a

scroll, but in the large clear

characters of a public document.

What these characters exactly

were, a recent discovery has

enabled us to learn.

Hebrew

inscriptions of an early date

have long been sought for in

vain. We knew of one or two

inscribed fragments from the

neighbourhood of the Pool of

Siloam at Jerusalem, and of a

few seals which might be referred

to the period before the

Babylonish Captivity; but,

unfortunately, none of these

could be assigned to a definite

date, and even the conclusion

that some of them were

pre-exilic was after all little

more than a guess. The seals are

usually distinguished by the

absence of any symbols or other

devices, as well as by a

horizontal line drawn across the

middle, which divides the

inscription into two halves. The

proper names also which occur on

them are, in the majority of

cases, compounded with the

sacred name Yahveh. Several of

these seals have been found in

Babylonia and Mesopotamia, and

may therefore be regarded as

memorials of the Jewish exile.

But the legends they bear are

always short, and consist of

little else than proper names;

and as their date was uncertain,

it was impossible to draw any

solid inferences from them as to

the character of the writing

employed in Judah or Israel

before the age of

Nebuchadnezzar.

It is quite

otherwise now. An inscription of

some length has been discovered

in Jerusalem itself, which is

certainly as old as the time of

Isaiah, and may be older still.

In the summer of 1880, one of

the native pupils of Mr. Schick,

a German architect long settled

in Jerusalem, was playing with

some other lads in the so-called

Pool of Siloam, and while wading

up a channel cut in the rock

which leads into the Pool,

slipped and fell into the water.

On rising to the surface, he

noticed what looked like letters

on the rock which formed the

southern wall of the channel. He

told Mr. Schick of what he had

seen; and the latter, on

visiting the spot, found that an

ancient inscription, concealed

for the most part by the water,

actually existed there.

The Pool is of

comparatively modern

construction, but it encloses

the remains of a much older

reservoir, which, like the

modern one, was supplied with

water through a tunnel excavated

in the rock. This tunnel

communicates with the so-called

Spring of the Virgin, the only

natural spring of water in or

near Jerusalem. It rises below

the walls of the city, on the

western bank of the valley of

the Kidron; and the tunnel

through which its waters are

conveyed is consequently cut

through the ridge, that forms

the southern part of the Temple

Hill. The Pool of Siloam lies on

the opposite side of this ridge,

at the mouth of the valley

called that of the Cheesemakers

(Tyropϙn) in the time of

Josephus, but which is now

filled up with rubbish, and in

large part built over. According

to Lieutenant Conder's

measurements, the length of the

tunnel is 1,708 yards; it does

not, however, run in a straight

line, and towards the centre

there are two culs

de sac,

of which the inscription now

offers an explanation. At the

entrance on the western or

Siloam side its height is about

sixteen feet; but the roof grows

gradually lower, until in one

place it is not quite two feet

above the floor of the passage.

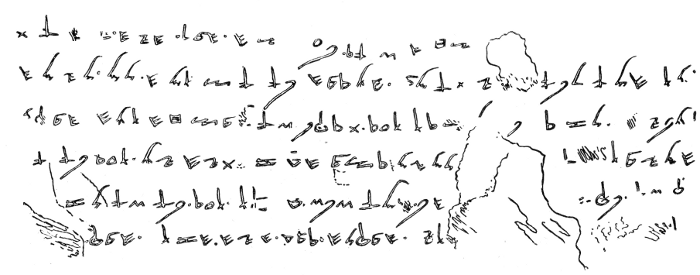

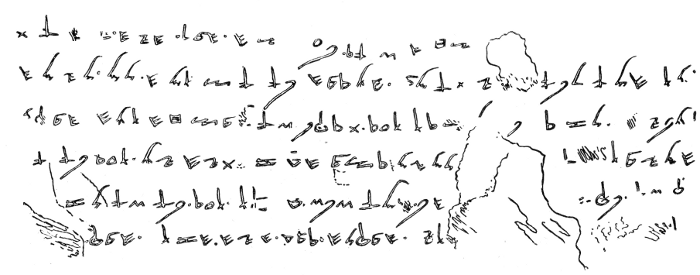

The Siloam

Inscription (tracing from a

squeeze, taken 15th July, 1881,

by Lieuts. Conder and Mantell,

R. E.).

The inscription

occupies the under part of an

artificial tablet in the wall of

rock, about nineteen feet from

where the conduit opens out upon

the Pool of Siloam, and on the

right-hand side of one who

enters it. After lowering the

level of the water, Mr. Schick

endeavoured to take a copy of

it; but as not only the letters

of the text, but every flaw in

the rock were filled with a

deposit of lime left by the

water, all he could send to

Europe was a collection of

unmeaning scrawls. Besides the

difficulty of distinguishing the

letters, it was also necessary

to sit in the mud and water, and

to work by the dim light of a

candle, as the place where the

inscription is engraved is

perfectly dark. All this

rendered it impossible for

anyone not acquainted with

Phœnician palæography to make an

accurate transcript. The first

intelligible copy accordingly

was made by Professor Sayce

after several hours of careful

study; but this too contained

several doubtful characters, the

real forms of which could only

be determined by the removal of

the calcareous matter with which

they were coated. In March,

1881, six weeks after Sayce's

visit, Dr. Guthe arrived in

Jerusalem, and after making a

more complete facsimile of the

inscription than had previously

been possible, removed the

deposit of lime by means of an

acid, and so revealed the

original appearance of the

tablet. Letters which had

previously been concealed now

became visible, and the exact

shapes of them all could be

observed. First a cast, and then

squeezes of the text were taken;

and the scholars of Europe had

at last in their hands an exact

copy of the old text.

The inscription

consists of six lines, but

several of the letters composing

it have unfortunately been

destroyed by the wearing away of

the rock. The translation of it

is as follows:—

1. “(Behold)

the excavation! Now this is the

history of the excavation. While

the excavators were still

lifting up the pick, each

towards his neighbour, and while

there were yet three cubits to

(excavate, there was heard) the

voice of one man calling to his

neighbour, for there was an

excess in the rock on the right

hand (and on the left). And

after that on the day of

excavating the excavators had

struck pick against pick, one

against the other, the waters

flowed from the spring to the

Pool for a distance of 1,200

cubits. And (part) of

a cubit was the height of the

rock over the head of the

excavators.”

The language of

the inscription is the purest

Biblical Hebrew. There is only

one word in it—that rendered “excess”—which

is new, and consequently of

doubtful signification. We learn

from it that the engineering

skill of the day was by no means

despicable. The conduit was

excavated in the same fashion as

the Mont Cénis tunnel of our own

time, by beginning the work

simultaneously at the two ends;

and, in spite of its windings,

the workmen almost succeeded in

meeting in the middle. They

approached, indeed, so nearly to

one another, that the noise made

by the one party in hewing the

rock was heard by the other, and

the small piece of rock which

intervened between them was

accordingly pierced. This

accounts for the two culs

de sac now

found in the centre of the

channel; they represent the

extreme points reached by the

two bands of excavators before

they had discovered that,

instead of meeting, they were

passing by one another.

It is most

unfortunate that the inscription

contains no indication of date;

but the forms of the letters

used in it show that it cannot

be very much later in age than

the Moabite Stone. Indeed, some

of the letters exhibit older

forms than those of the Moabite

Stone; but this may be explained

by the supposition that the

scribes of Jerusalem were more

conservative, more disposed to

retain old forms, than the

scribes of king Mesha. The

prevalent opinion of scholars is

that the tunnel and consequently

the inscription in it were

executed in the reign of

Hezekiah. According to the

Chronicler (2 Chr. xxxii. 30),

Hezekiah “stopped

the upper watercourse of Gihon,

and brought it straight down to

the west side of the

city of David,” and we

read in 2 Kings xx. 20, that “he

made a pool and a conduit, and

brought water into the city.” The

object of the laborious

undertaking is very plain. The

Virgin's Spring, the only

natural source near Jerusalem,

lay outside the walls, and in

time of war might easily pass

into the hands of the enemy. The

Jewish kings, therefore, did

their best to seal up this

spring, which must be the

Chronicler's “upper

water-course of Gihon,” and

to bring its waters by

subterranean passages inside the

city walls. Besides the tunnel

which contains the inscription

another tunnel has been

discovered, which also

communicates with the Virgin's

Spring. But it is tempting to

suppose that the most important

of these—the tunnel which

contains the inscription—must be

the one which Hezekiah made.

The supposition,

however, is rendered uncertain

by a statement of Isaiah (viii.

6). While Ahaz, the father of

Hezekiah, was still reigning,

Isaiah uttered a prophecy in

which he made allusion to “the

waters of Shiloah that go

softly.” Now

this can hardly refer to

anything else than the gently

flowing stream which still runs

through the tunnel of Siloam. In

this case the conduit would have

been in existence before the

time of Hezekiah; and, since we

know of no earlier period when a

great engineering work of the

kind could have been executed

until we go back to the reign of

Solomon, it is possible that the

inscription may actually be of

this ancient date. The inference

is supported by the name Shiloah,

which probably means “the

tunnel,” and

would have been given to the

locality in consequence of the

conduit which here pierced the

rock. It was not likely that

when David and Solomon were

fortifying Jerusalem, and

employing Phœnician architects

upon great public buildings

there, they

would have allowed the city to

depend wholly upon rain cisterns

for its water supply. Since the

inscription calls the Pool of

Siloam simply “the

Pool,” we

may perhaps infer that no other

reservoir of the kind was in

existence at the time; and yet

in the age of Isaiah, as we

learn from Isa. xxii. 9, 11,

there was not only “a

lower pool,” in

contradistinction to “an

upper one,” but

also “an

old pool,” in

contradistinction to a new one.

As Dr. Guthe's excavations have

laid bare the remains of four

such pools in the neighbourhood

of that of Siloam, there is no

difficulty in finding places for

all these reservoirs. But they

could hardly have existed when

the Pool of Siloam was still

known as simply “the

Pool,” nor

could the name of Shiloah have

well been given to the locality

if another tunnel, observed by

Sir Charles Warren on the

eastern side of the Temple Hill,

had been already excavated. This

second tunnel starts, like the

Siloam one, from the Virgin's

Spring, and was designed to

bring the water of the spring

within the walls of the city. A

shaft is cut for seventy feet

into the hill, where it meets

another perpendicular shaft,

which rises for a height of

fifty feet, and then meets a

flight of steps, which lead into

a broad passage, ending in

another flight of steps and a

vaulted chamber. Niches for

lamps were found here at

intervals, intended to light the

persons who went to draw the

water by means of a bucket. As

lamps of the Roman period were

discovered in the chamber, the

tunnel must have been known and

used up to the time of the

capture of Jerusalem by Titus,

and it is probably not older

than the reign of Herod. In any

case, the comparative excellence

of its workmanship goes to show

that it was made at a later date

than the tunnel of Siloam.

Whatever doubts,

however, may still hang over the

date of the inscription, there

can be no question that it has

thrown most important light on

the topography of Jerusalem in

the period of the kings. It is

now clear that the modern city

occupies very little of the same

ground as the ancient one; the

latter stood entirely on the

rising ground to the east of the

Tyropϙn valley, the northern

portion of which is at present

occupied by the mosque of Omar,

while the southern portion is

uninhabited. The Tyropϙn valley

itself must be the Valley of the

Son of Hinnom, where the

idolaters of Jerusalem burnt

their children in the fire to

Moloch. It must be in the

southern cliff of this valley

that the tombs of the kings are

situated; the reason why they

have never yet been found being

that they are buried under the

rubbish with which the valley is

filled. Among the rubbish must

be the remains of the city which

was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar,

and whose ruins were flung into

the gorge below. Between the

higher part of the hill, now

occupied by the mosque of Omar,

and its lower uninhabited

portion, Dr. Guthe has

discovered traces of a valley

which once ran into the valley

of the Kidron at right angles to

it, not far from the Virgin's

Spring, and divided in old days

the City of David from the rest

of the town. Here, as well as in

the now obliterated Valley of

the Cheesemakers, there probably

still lie the relics of the

dynasty of David; but we shall

only know the story they have to

tell us when the spade of the

excavator has come to continue

the discoveries which the

inscription of Siloam has begun.

|

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD