|

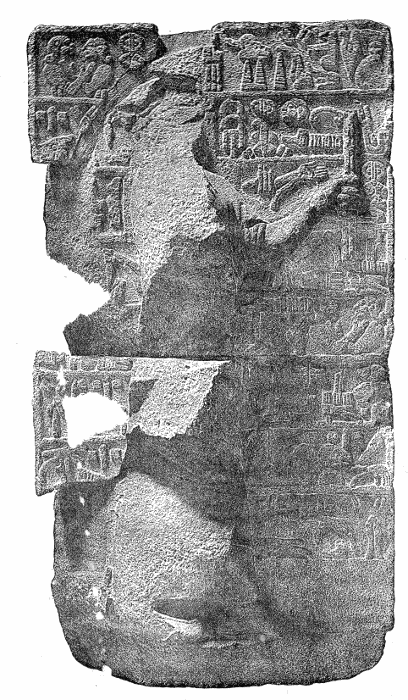

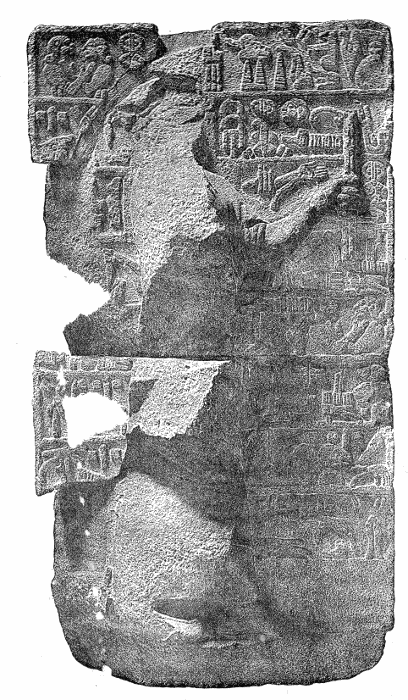

Monument of a

Hittite king, accompanied by an

inscription in Hittite

hieroglyphics, discovered on the

site of Carchemish and now in

the British Museum.

The object of this little book

is explained by its title.

Discovery after discovery has

been pouring in upon us from

Oriental lands, and the accounts

given only ten years ago of the

results of Oriental research are

already beginning to be

antiquated. It is useful,

therefore, to take stock of our

present knowledge, and to see

how far it bears out that “old

story” which has been

familiar to us from our

childhood. The same spirit of

scepticism which had rejected

the early legends of Greece and

Rome had laid its hands also on

the Old Testament, and had

determined that the sacred

histories themselves were but a

collection of myths and fables.

But suddenly, as with the wand

of a magician, the ancient

eastern world has been

reawakened to life by the spade

of the explorer and the patient

skill of the decipherer, and we

now find ourselves in the

presence of monuments which bear

the names or recount the deeds

of the heroes of Scripture. One

by one these “stones

crying out” have been

examined or more perfectly

explained, while others of equal

importance are being continually

added to them.

What striking confirmations of

the Bible narrative have been

afforded by the latest

discoveries will be seen from

the following pages. In many

cases confirmation has been

accompanied by illustration.

Unexpected light has been thrown

upon facts and statements

hitherto obscure, or a wholly

new explanation has been given

of some event recorded by the

inspired writer. What can be

more startling than the

discovery of the great Hittite

Empire, the very existence of

which had been forgotten, and

which yet once contended on

equal terms with Egypt on the

one side and Assyria on the

other? The allusions to the

Hittites in the Old Testament,

which had been doubted by a

sceptical criticism, have been

shown to be fully in accordance

with the facts, and their true

place in history has been

pointed out.

But the account of the Hittite

Empire is not the only discovery

of the last four or five years

about which this book has to

speak. Inscriptions of Sargon

have cleared up the difficulties

attending the tenth and eleventh

chapters of Isaiah's prophecies,

and have proved that no “ideal” campaign

of an “ideal” Assyrian

king is described in them. The

campaign, on the contrary, was a

very real one, and when Isaiah

delivered his prophecy the

Assyrian monarch was marching

down upon Jerusalem from the

north, and was about to be “the

rod” of God's anger upon

its sins. Ten years before the

overthrow of Sennacherib's army

his father, Sargon, had aptured

Jerusalem, but a “remnant” escaped

the horrors of the siege, and

returned in penitence “unto

the mighty God.”

Perhaps the most remarkable of

recent discoveries is that which

relates to Cyrus and his

conquest of Babylonia. The

history of the conquest as told

by Cyrus himself is now in our

hands, and it has obliged us to

modify many of the views, really

derived from Greek authors,

which we had read into the words

of Scripture. Cyrus, we know now

upon his own authority, was a

polytheist, and not a

Zoroastrian; he was king of

Elam, not of Persia. It was

Elam, and not Persia, as

Isaiah's prophecies declared,

which invaded Babylon. Babylon

itself was taken without a

siege, and Mr. Bosanquet may

therefore have been right in

holding that the Darius of

Daniel was Darius the son of

Hystaspes.

Hardly less interesting has been

the discovery of the inscription

of Siloam, which reveals to us

the very characters used by the

Jews in the time of Isaiah,

perhaps even in the time of

Solomon himself. The discovery

has cast a flood of light on the

early topography of Jerusalem,

and has made it clear as the

daylight that the Jews of the

royal period were not the rude

and barbarous people it has been

the fashion of an unbelieving

criticism to assume, but a

cultured and literary

population. Books must have been

as plentiful among them as they

were in Phœnicia or Assyria;

nor must

we forget the results of the

excavations undertaken last year

in the land of Goshen. Pithom,

the treasure-city built by the

Israelites, has been

disinterred, and the date of the

Exodus has been fixed. M.

Naville has even found there

bricks made without straw.

But the old records of Egypt and

Assyria have a further interest

than a merely historical one.

They tell us what were the

religious doctrines and

aspirations of those who

composed them, and what was

their conception of their duty

towards God and man. We have

only to compare the hymns and

psalms and prayers of these

ancient peoples—seeking “the

Lord, if haply they might feel

after Him and find Him”—with

the fuller lights revealed in

the pages of the Old Testament,

to discover how wide was the

chasm that lay between the two.

The one was seeking what the

other had already found. The

Hebrew prophet was the

forerunner and herald of the

Gospel, and the light shed by

the Gospel had been reflected

back upon him. He saw already “the

Sun of Righteousness” rising

in the east; the psalmist of

Shinar or the devout worshipper

of Asshur were like unto those “upon

whom no day has dawned.”

|

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD