By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 7 - Assyria - Its Princes, Priests, and People

By A. H. Sayce M.A.

Chapter 3

Assyrian ReligionThe Assyrians derived the greater part of their deities and religious beliefs, like their literature and culture generally, from Babylonia. The Babylonian gods were the gods of Assyria also. Most of them were of Accadian or prś-Semitic origin, but the Semitic Babylonians, when they appropriated the civilisation of the Accadians, modified them in accordance with their own conceptions. The Accadians believed that every object and phenomenon of nature had its Zi or 'spirit,' some of them beneficent, others hostile to man, like the objects and phenomena they represented. Naturally, however, there were more malevolent than beneficent spirits in the universe, and there was scarcely an action which did not risk demoniac possession. Diseases were due to the malevolence of these spirits, and could be cured only by the use of certain charms and exorcisms. Exorcisms, in fact, gave those who employed them power over the spirits; they could by means of them compel the evil spirit to retire, and the beneficent spirit to approach. The knowledge of such exorcisms was in the hands of the priests, so that priest and magician were almost synonymous terms. Among the multitude of spirits feared by the Accadians, there were some which had been raised above the rest into the position of gods. Of these, Anu, 'the sky;' Mul-ge, 'the earth;' and Ea, 'the deep,' were the most conspicuous. At their side stood the 'spirits' of the heavenly bodies—the Moon-god, the Sun-god, the evening star, and the other planets. The Moon-god ranked before the Sun-god, as might indeed have been expected to be the case among a nation of astronomers like the Chaldeans. When the Semitic Babylonians adopted the deities of their predecessors and teachers, Anu and his compeers lost much of their elemental nature, while the Sun-god Samas came to assume an important place. The religion of the Babylonian Semites, in fact, was essentially solar; the Sun-god was addressed as Bel or Baal, the supreme 'lord,' and adored under various forms. He appeared to them, moreover, under two aspects, sometimes as the kindly deity who gives life and light to all things, sometimes as the scorching sun of summer who demanded the sacrifice of the first-born to appease his wrath. Sometimes, again, he was worshipped as the young and beautiful Tammuz, slain by the boar's tusk of winter; whose death was lamented at the autumnal equinox, and who was invoked as adoni (Adonis) or 'master.' Unlike the Accadians, who did not distinguish gender, the Semites divided all nouns into masculines and feminines. By the side of the god, consequently, stood the goddess. She was, however, but a pale reflection of her male consort, created, so to speak, by the necessities of grammar. She had no independent attributes of her own; Beltis, or Bilat, the wife of Bel, was nothing more than the feminine complement of the god. The Accadians had known of one great goddess, Istar, the evening star; but Istar was an independent deity, with attributes as strongly and individually marked as those of the gods. Among the Semites, Istar became Ashtoreth, with the feminine suffix th, and though in Babylonia the old legends and traditions prevented her from losing altogether her primitive character, she tended more and more to pass into the mere reflection of some male deity. Just as the gods could be collectively spoken of as Baalim or 'lords,' all being regarded as so many different forms of the Sun-god, the goddesses also were termed Ashtaroth or 'Ashtoreths.' We see, therefore, that in adopting the pantheon of Accad, the Semites made three important changes. The Sun-god was assigned a leading place in worship and belief; female deities were introduced, who were, however, mere reflections of the gods; while the inferior deities of the Accadians were classed among 'the 300 spirits of heaven' and 'the 600 spirits of earth,' only a few of the more prominent ones retaining their old position. These latter may be grouped as follows:— At the head of the divine hierarchy still stood the old triad of Anu, Mul-ge, and Ea. Mul-ge's name, however, was changed to Bel, but since Merodach was also known as Bel, he fell more and more into the background, especially after the rise of Babylon, of which city Merodach was the patron deity. At Nipur, now Niffer, alone, he continued to be worshipped down into late times. His consort was Bilat, or Beltis, 'the great lady,' who eventually came to be regarded as the wife of Merodach rather than of 'the other Bel.' Like Anu and Ea, Bel was the offspring of Sar and Kisar, the upper and lower firmaments. Anu was the visible sky, but he also represented the invisible heaven, which was supposed to extend above the visible one, and to be the abode of the gods. The chief seat of his worship was Erech, where he was regarded as the oldest of the gods, and the original creator of the universe. But elsewhere, also, he was looked upon as the creator of the visible world, and the father of the gods. By his side, in the Semitic period, stood the goddess Anat, whose attributes were derived from his. The worship of Anat spread from Babylonia to the Canaanites, as is shown by the geographical names Beth Anath, 'the temple of Anat' (Josh. xix. 38; xv. 59), and Anathoth, the city of 'the goddesses Anat.' It was even introduced into Egypt after the Asiatic wars of the eighteenth dynasty. In the prś-Semitic days of Chaldea, a monotheistic school had flourished, which resolved the various deities of the Accadian belief into manifestations of the one supreme god, Anu; and old hymns exist in which reference is made to 'the one god.' But this school never seems to have numbered many adherents, and it eventually died out. Its existence, however, reminds us of the fact that Abraham was born in 'Ur of the Chaldees.' Ea originally represented the ocean-stream or 'great deep,' which was supposed to surround the earth like a serpent, and by which all rivers and springs were fed. He was symbolised by the snake, and was held to be the creator and benefactor of mankind. One of his most frequent titles is 'lord of wisdom,' and the chief seat of his worship was at Eridu, 'the holy city,' near which was the sacred grove or 'garden,' the centre of the world, where the tree of life and knowledge had its roots. It was Ea who had given to mankind not only life, but all the arts and appliances of culture also, and it was his help that the Babylonian invoked when in trouble. He was emphatically the god of healing, who had revealed medicines to mankind. As god of the great deep, he was often figured as a man with the tail of a fish, and in this form was known to the Greeks under the name of Oannes or 'Ea the fish.' Sometimes the skin of a fish was suspended behind his back. Oannes, it was said, had in early days ascended out of the Persian Gulf, and taught the first inhabitants of Babylonia letters, science, and art, besides writing a history of the origin of mankind and their different ways of life. His wife was Dav-kina, 'the lady of the earth,' who presided over the lower world. Among the numerous offspring of Ea and Dav-kina, Merodach held the foremost place. He was originally a form of the Sun-god, regarded under his beneficent aspect, and was believed to be ever engaged in combating the powers of evil, and in performing services for mankind. Hence he is addressed as 'the redeemer of mankind,' 'the restorer to life,' and the 'raiser from the dead,' and a considerable number of the religious hymns are dedicated to him. He was believed to be continually passing backwards and forwards between the earth and the heaven where Ea dwelt, informing Ea of the sufferings of men, and returning with Ea's directions how to relieve them. One of the bas-reliefs from Nineveh, now in the British Museum, represents him as pursuing with his curved sword or thunderbolt the demon Tiamat, the personification of chaos and anarchy, who is depicted with claws, tail, and horns. As we have already seen, he was commonly addressed as Bel or 'lord,' and so came gradually to supplant the older Bel or Mul-ge. Among the planets his star was Jupiter. His wife was Zarpanit or Zirat-panitu, in whom some scholars have seen the Succoth-benoth of 2 Kings xvii. 30. The children of Merodach and Zarpanit were Nebo, 'the prophet,' and his wife Tasmit, 'the hearer.' Nebo was the god of oratory and literature; it was he who 'enlightened the eyes' to understand written characters, while his wife 'enlarged the ears,' so that they could comprehend what was read. The origin of the cuneiform system of writing was ascribed to Nebo. To him was dedicated 'the temple of the Seven Lights of Heaven and Earth,' at Borsippa, the suburb of Babylon, which is now known to the Arabs as the Birs-i-NimrŻd, and his worship was carried as far as Canaan, as we may gather from such names as the city of Nebo, in Judśa (Ezra ii. 29), and Mount Nebo, in Moab (Deut. xxxii. 49). In Accadian he had been called Dimsar, 'the tablet-writer,' and a temple was erected to him in the island of Bahrein, in the Persian Gulf, where he was worshipped under the name of Enzak. As a planetary deity, he was identified with Mercury. He was often adored under the name of Nusku, although Nusku had originally been a separate divinity, and the same, perhaps, as the Nisroch of the Bible (2 Kings xix. 37). The companion of Merodach was Rimmon, or rather Ramman, 'the thunderer.' He represented the atmosphere, and was accordingly the god of rain and storm, who was armed with the lightning and the thunderbolt. Sometimes he was dreaded as 'the destroyer of crops,' 'the scatterer of the harvest;' at other times prayers were made to him as 'the lord of fecundity.' His worship extended into Syria, where Rimmon appears to have been the supreme deity of Damascus, and where he was also known under the name of Hadad or Dadda. Two other elemental gods were Samas, the Sun-god, and Sin, the Moon-god. Samas was the son of Sin, in accordance with the astronomical view of the old Babylonians, which made the moon the measurer of time, and regarded the day as the offspring of night. Samas, however, like Saul or Savul, another deity of whom mention is made in the inscriptions, was really but a form of Merodach, though in historical times the two divinities were separated from one another, and received different cults. Samas, again, was originally identical with Tammuz; but when Tammuz came to denote only the sun of spring and summer, while the myth that associated him with Istar laid firm hold of men's minds, Tammuz assumed separate attributes, and an individual existence apart from Samas. Sin, the Moon-god, was termed Agu or Acu by the Accadians, and if the name of Mount Sinai was derived from him, as is sometimes supposed, we should have evidence that he was known and worshipped in Northern Arabia. At all events he was one of the deities of Southern Arabia. Sin was the patron-god of the city of Ur, and it was to him that the Assyrian kings traced the formation of their kingdom. One of the most famous of his temples was in the ancient city of Harran, where he was symbolised by an upright cone of stone. As the emblem of the Sun-god was the solar orb, the emblem of Sin was the crescent moon. According to some of the legends of Babylonia, the daughter of the Moon-god was the goddess Istar. Other legends, however, placed Istar among the older gods, and made her the daughter of Anu, the sky. In either case she was at the outset the goddess of the evening star, and when it was discovered that the evening and morning stars were the same, of the morning star also. As the evening star, she was known as Istar of Erech, as the morning star, she was identified with Anunit or Anat, the goddess of Accad. At times she was also regarded as androgynous, both male and female. Istar was the chief of the Accadian goddesses, and she retained her rank even among the Semites, who, as we have seen, looked upon the goddess as the mere consort and shadow of the god. But Istar continued to the last a separate and independent divinity. She presided over love and war, as well as over the chase. She was invoked as 'the queen of heaven,' 'the queen of all the gods,' and there was often a tendency to merge in her the other goddesses of the pantheon. Her principal temples were at Erech, Nineveh, and Arbela, but altars were erected to her in almost every place, and she was adored under as many forms and titles as she possessed shrines. Her name and worship spread through the Semitic world, in Southern Arabia, in Syria, in Moab, where she was identified with the Sun-god, Chemosh, and in Canaan, where she was called Ashtoreth, the AstartÍ of the Greeks. But the Greeks also knew her as AphroditÍ, the goddess whom they had borrowed from the Phœnicians of Canaan, and we may discover her again in the Ephesian Artemis. The rites performed in her temples made Istar or Ashtoreth the darkest blot in Assyrian and Canaanitish religion, and excited the utmost horror and indignation of the prophets of God. When the moon came to be conceived as a female divinity, the pale reflection, as it were, of the sun, Istar, the evening star, became also the goddess of the moon. Hence it is that 'the queen of heaven' (Jer. xliv. 17) passed into AstartÍ 'with crescent horns.' One of the most popular of old Babylonian myths told how Istar had wedded the young and beautiful Sun-god, Tammuz, 'the only-begotten,' and had descended into Hades in search of him when he had been slain by the boar's tusk of winter. A portion of a Babylonian poem has been preserved to us, which describes her passage through the seven gates of the underworld, where she left with the warden of each some one of her adornments, until at last she reached the seat of the infernal goddess Allat, stripped and bare. There she remained imprisoned until the gods, wearied of the long absence of the goddess of love, created a hound called 'the renewal of light,' who restored her to the upper world. The myth clearly refers to the waning and waxing of the monthly moon, and must therefore have originated when Istar had already become the goddess of the moon. The myth entered deeply into the religious belief of the worshippers of Istar. The Accadians called the month of August 'the month of the errand of Istar,' while June was termed 'the month of Tammuz' by the Semites. It was then that, as Milton writes, his

But it was not only in Assyria and Phœnicia that the death of Tammuz was lamented by the women year by year. The infection spread to Judah also, and even in Jerusalem, within the precincts of the temple itself, Ezekiel saw 'women weeping for Tammuz' (Ezek. viii. 14).

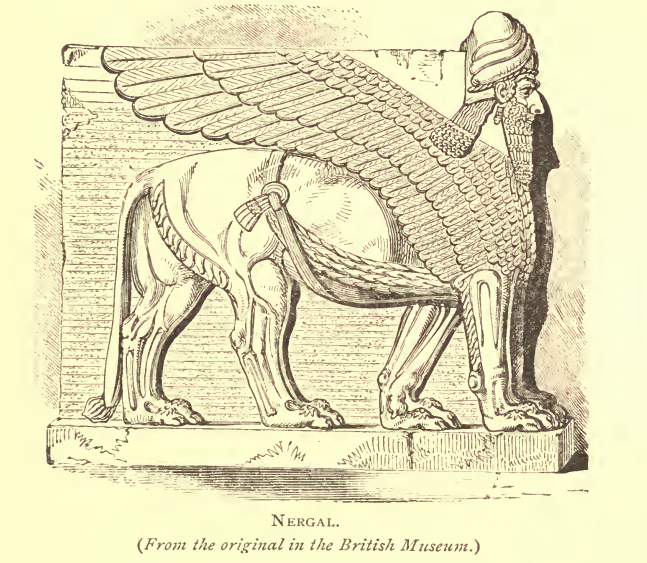

Nergal There are only two other Assyro-Babylonian deities who need be mentioned, Nergal and Adar. Nergal was the presiding deity of Cuthah and its vast necropolis.3 He shared with Anu the privilege of superintending the regions of the dead, and he was also a god of hunting and war. His name, like those of Anu, Ea, and Istar, was of Accadian origin. Adar, the son of Beltis, was one of those solar deities who were formed by worshipping the Sun-god under some particular attribute. The reading of his name is, unfortunately, not certain, and Adar is only its most probable pronunciation. If it is correct, Adar will be the deity meant in 2 Kings xvii. 31, where it is stated that the people of Sepharvaim, or the two Sipparas, burnt their children in fire to Adrammelech and Anammelech, that is to say, to 'King Adar' and 'King Anu.' Such were the principal divinities of Babylonia and Assyria. But the Assyrians had another also, whom they exalted above all the rest. This was Assur, the divine impersonation of the state and empire. It was Assur who, according to the Assyrian kings, led them to victory, and the cruelties they practised on the conquered were, they held, judgments exercised against those who would not believe in him. Assur, in the form of an archer, is sometimes represented on the monuments in the midst of the winged solar disk, and above the head of the monarch, whom he protects from his enemies. The Assyrian, however, was not so pious or superstitious as his Babylonian neighbour. The Babylonian lived in perpetual dread of the evil spirits which thronged about him; almost every moment had its religious ceremony, almost every action its religious complement. Not only had the State ritual to be attended to; the unceasing attacks of the demons could be warded off only by magical incantations and the intervention of the sorcerer-priest. But the Assyrians were too much occupied with wars and fighting to give all this heed to the requirements of religion. It is significant that, whereas in Babylonia we find the remains of scarcely any great buildings except temples, the great buildings of Assyria were the royal palaces. The libraries, which in Babylonia were stored in the temples, were deposited in Assyria in the palace of the king. Nevertheless, the greater part of the religious system of Babylonia had been transported into Assyria. Along with the Babylonian deities had come the Babylonian scriptures. These were divided into two great collections or volumes. The first, and oldest, was a collection of exorcisms and magical texts, by the use of which, it was believed, the spirits of evil could be driven away, and the spirits of good induced to visit the reciter. When, however, certain independent deities began to emerge from among the multitudinous 'spirits' of the primitive Accadian creed, hymns were composed in their honour, and these hymns were eventually collected together, and, like the Rig-Veda of India, became a second sacred book. After the Accadians had been supplanted by the Semites, the Accadian language, in which the hymns were originally written, was provided with a Semitic translation; but it was still considered necessary to recite the exact words of the original, since the words themselves were sacred, and any mistake in their pronunciation would invalidate the religious service in which they were employed. Some of the incantations embodied in the collection of exorcisms must have been introduced into it subsequently to the compilation of the sacred hymns, since the latter are found inserted in them. From this it would appear that the older collection continued to receive additions for a long while after the younger collection—that of the sacred hymns—had been put together and invested with a sacred character. This could not have been till after the beginning of the Semitic period, since there are a few hymns which do not seem to have had any Accadian originals. If we may compare the two collections with our own religious literature, we may say that the collection of hymns corresponded more to our Bible, that of exorcisms to our Prayer Book. The Babylonians and Assyrians, however, possessed a liturgy which answered far better to our conception of what a Prayer Book should be. This contained services for particular days and hours, together with rubrics for the direction of the priest. Thus we are told that 'in the month Nisan, on the second day, two hours after nightfall, the priest [of Bel at Babylon] must come and take of the waters of the river, must enter into the presence of Bel, and change his dress; must put on a robe in the presence of Bel, and say this prayer: "O my lord who in his strength has no equal, O my lord, blessed sovereign, lord of the world, speeding the peace of the great gods, the lord who in his might destroys the strong, lord of kings, light of mankind, establisher of trust, O Bel, thy sceptre is Babylon, thy crown is Borsippa, the wide heaven is the dwelling-place of thy liver.... O lord of the world, light of the spirits of heaven, utterer of blessings, who is there whose mouth murmurs not of thy righteousness, or speaks not of thy glory, and celebrates not thy dominion? O lord of the world, who dwellest in the temple of the sun, reject not the hands that are raised to thee; be merciful to thy city Babylon, to Beth-Saggil thy temple incline thy face, grant the prayers of thy people the sons of Babylon."' Part of the liturgy consisted of prayers addressed to the various deities, and suited to various occasions. Here are examples of them: 'At dawn and in the night prayer should be made to the throne-bearer, and thus should it be said: "O throne-bearer, giver of prosperity, a prayer!" After that, let prayer be made to Nusku, and thus let it be said: "O Nusku, prince and king of the secrets of the great gods, a prayer!" After that, let prayer be made to Adar, and thus let it be said: "O Adar, mighty lord of the deep places of the springs, a prayer!" After that let prayer be made to Gula (Beltis), and thus let it be said: "O Gula, mother, begetter of the black-headed race (of Accadians), a prayer!" After that, let prayer be made to Nin-lil, and thus let it be said: "O Nin-lil, great goddess, wife of the divine prince of sovereignty, a prayer!" After that, let prayer be made to Bel, and thus let it be said: "O lord supreme, establisher of law, a prayer!" The prayer (must be repeated) during the day at dawn, and in the night, with face and mouth uplifted, during the middle watch. Water must be poured out in libation day by day ... at dawn, on the beams of the palace.' One of the most curious of these petitions is a prayer after a bad dream, of which a fragment only has been found. This reads as follows: 'May the lord set my prayer at rest, (may he remove) my heavy (sin). May the lord (grant) a return of favour. By day direct unto death all that disquiets me. O my goddess, be gracious unto me; when (wilt thou hear) my prayer? May they pardon my sin, my wickedness, (and) my transgression. May the exalted one deliver, may the holy one love. May the seven winds carry away my groaning. May the worm lay it low, may the bird bear it upwards to heaven. May a shoal of fish carry it away; may the river bear it along. May the creeping thing of the field come unto me; may the waters of the river as they flow cleanse me. Enlighten me like a mask of gold. Food and drink before thee perpetually may I get. Heap up the worm, take away his life. The steps of thy altar, thy many ones, may I ascend. With the worm make me pass, and may I be kept with thee. Make me to be fed, and may a favourable dream come. May the dream I dream be favourable; may the dream I dream be fulfilled. May the dream I dream turn to prosperity. May Makhir, the god of dreams, settle upon my head. Let me enter Beth-Saggil, the palace of the gods, the temple of the lord. Give me unto Merodach, the merciful, to prosperity, even unto prospering hands. May thy entering (O Merodach) be exalted, may thy divinity be glorious; may the men of thy city extol thy mighty deeds.' Along with these prayers, the Assyrians possessed a collection of penitential psalms, which were composed at a very remote period in Southern Babylonia. The most perfect of those of which we have copies is the following:—

A rubric is attached to this verse, stating that it is to be repeated ten times, and at the end of the whole psalm is the further rubric: 'For the tearful supplication of the heart let the glorious name of every god be invoked sixty-five times, and then the heart shall have peace.' Reference is made in the psalm to the eating of forbidden foods, and we have other indications that certain kinds of food, among which swine's flesh may be mentioned, were not allowed to be consumed. On particular days also fasts were observed, and special days of fasting and humiliation were prescribed in times of public calamity. In the calendar of the Egibi banking firm, the 2nd of Tammuz or June is entered as a day of 'weeping.' The institution of the Sabbath, moreover, was known to the Babylonians and Assyrians, though it was confounded with the feast of the new moon, since it was kept, not every seven days, but on the seventh, fourteenth, twenty-first, and twenty-eighth days of the lunar month. On these days, we read in a sort of Saints' calendar for the intercalary Elul: 'Flesh cooked on the fire may not be eaten, the clothing of the body may not be changed, white garments may not be put on, a sacrifice may not be offered, the king may not ride in his chariot, nor speak in public, the augur may not mutter in a secret place, medicine of the body may not be applied, nor may any curse be uttered.' The very name of Sabattu or Sabbath was employed by the Assyrians, and is defined as 'a day of rest for the heart,' while the Accadian equivalent is explained to mean 'a day of completion of labour.' So far as we are at present acquainted with the peculiarities of the Assyro-Babylonian temple, it offers many points of similarity to the temple of Solomon at Jerusalem. Thus there were an outer and an inner court and a shrine, to which the priests alone had access. In this was an altar approached by steps, as well as an ark or coffer containing two inscribed tablets of stone, such as were discovered by Mr. Rassam in the temple of Balaw‚t. In the outer court was a large basin, filled with water, and called 'a sea,' which was used for ablutions and religious ceremonies. At the entrance stood colossal figures of winged bulls, termed 'cherubs,' which were imagined to prevent the ingress of evil spirits. Similar figures guarded the approach to the royal palace, and possibly to other houses as well. Some of them may now be seen in the British Museum. Within, the temples were filled with images of gods, great and small, which not only represented the deities whose names they bore, but were believed to confer of themselves a special sanctity on the place wherein they were placed. As among the Israelites, offerings were of two kinds, sacrifices and meal offerings. The sacrifice consisted of an animal, more usually a bullock, part of whose flesh was burnt upon the altar, while the rest was handed over to the priests or retained by the offerer. There is no trace of human sacrifices among the Assyrians, which is the more singular, since we learn that human sacrifice had been an Accadian institution. A passage in an old astrological work indicates that the victims were burnt to death, like the victims of Moloch; and an early Accadian fragment expressly states that they were to be the children of those for whose sins they were offered to the gods. The fragment is as follows: 'The son who lifts his head among men, the son for his own life must (the father) give; the head of the child for the head of the man must he give; the neck of the child for the neck of the man must he give; the breast of the child for the breast of the man must he give.' The idea of vicarious punishment is here clearly indicated. The future life to which the Babylonian had looked forward was dreary enough. Hades, the land of the dead, was beneath the earth, a place of darkness and gloom, from which 'none might return,' where the spirits of the dead flitted like bats, with dust alone for their food. Here the shadowy phantoms of the heroes of old time sat crowned, each upon his throne, a belief to which allusion is made by the Hebrew prophet in his prophecy of the coming overthrow of Babylon (Is. xiv. 9). In the midst stood the palace of Allat, the queen of the underworld, where the waters of life bubbled forth beside the golden throne of the spirits of earth, restoring those who might drink of them to life and the upper air. The entrance to this dreary abode of the departed lay beyond Datilla, the river of death, at the mouth of the Euphrates, and it was here that the hero Gisdhubar saw Xisuthros, the Chaldean Noah, after his translation to the fields of the blessed. In later times, when the horizon of geographical knowledge was widened, the entrance to the gloomy world of Hades, and the earthly paradise that was above it, were alike removed to other and more unknown regions. The conception of the after-life, moreover, was made brighter, at all events, for the favoured few. An Assyrian court-poet prays thus on behalf of his king: 'The land of the silver sky, oil unceasing, the benefits of blessedness may he obtain among the feasts of the gods, and a happy cycle among their light, even life everlasting, and bliss; such is my prayer to the gods who dwell in the land of Assur.' Even at a far earlier time we find the great Chaldean epic of Gisdhubar concluding with a description of the blissful lot of the spirit of Ea-bani: 'On a couch he reclines and pure water he drinks. Him who is slain in battle thou seest and I see. His father and his mother (support) his head, his wife addresses the corpse. His friends in the fields are standing; thou seest (them) and I see. His spoil on the ground is uncovered; of his spoil he hath no oversight, (as) thou seest and I see. His tender orphans beg for bread; the food that was stored in (his) tent is eaten.' Here the spirit of Ea-bani is supposed to behold from his couch in heaven the deeds that take place on the earth below. Heaven itself had not always been 'the land of the silver sky' of later Assyrian belief. The Babylonians once believed that the gods inhabited the snow-clad peak of Rowandiz, 'the mountain of the world' and 'the mountain of the East,' as it was also termed, which supported the starry vault of heaven. It is to this old Babylonian belief that allusion is made in Isaiah xiv. 13, 14, where the Babylonian monarch is represented as saying in his heart: 'I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God: I will sit also on the mount of the assembly (of the gods)4 in the extremities5 of the north: I will ascend above the heights of the clouds.' As in all old forms of heathen faith, religion and mythology were inextricably mixed together. Myths were told of most of the gods. Reference has already been made to the myth of Istar and Tammuz, the prototype of the Greek legend of AphroditÍ and Adonis. So, too, the Greek story of the theft of fire by Prometheus has its parallel in the Babylonian story of the god Zu, 'the divine storm-bird,' who stole the lightning of Bel, the tablet whereon the knowledge of futurity is written, and who was punished for his crime by the father of the gods. In reading the legend of the plague-demon Lubara, whom Anu sends to smite the evildoers in Babylon, Erech, and other places, we are reminded of the avenging angel of God whom David saw standing with a drawn sword over Jerusalem. One of the most curious of the Babylonian myths was that which told how the seven evil-spirits or storm-demons had once warred against the moon and threatened to devour it. Samas and Istar fled from the lower sky, and the Moon-god would have been blotted out from heaven had not Bel and Ea sent Merodach in his 'glistening armour' to rescue him. The myth is really a primitive attempt to explain a lunar eclipse, and finds its illustration in the dragon of the Chinese, who is still popularly believed by them to devour the sun or moon when an eclipse takes place. The primśval victory of light and order over darkness and chaos, which seems to be repeated whenever the sun bursts through a storm-cloud, was similarly expressed in a mythical form. It was the victory of Merodach over Tiamat,'the deep,' the personification of chaos and elemental anarchy. The myth was embodied in a poem, the greater part of which has been preserved to us. We are told how Merodach was armed by the gods with bow and scimetar, how alone he faced and fought the dragon Tiamat, driving the winds into her throat when she opened her mouth to swallow him, and how, finally, he cut open her body, scattering in flight 'the rebellious deities' who had stood at her side. Tiamat, or the watery chaos, is usually represented with wings, claws, tail, and horns, but she is also identified with 'the wicked serpent' of 'night and darkness,' 'the monstrous serpent of seven heads,' 'which beats the sea.' The most interesting of the old myths and traditions of Babylonia are those in which we can trace, more or less clearly, the lineaments of the accounts of the creation of the world and the early history of man, given us in the early chapters of Genesis. There was more than one legend of the creation. In a text which came from the library of Cuthah, it was described as taking place on evolutionary principles, the first created beings being the brood of chaos, men with 'the bodies of birds' and 'the faces of ravens,' who were succeeded by the more perfect forms of the existing world. But the library of Assur-bani-pal also contained an account of the creation, which bears a remarkable resemblance to that in the first chapter of Genesis. Unfortunately, however, it seems to have been of Assyrian and not Babylonian origin, and, therefore, not to have been of early date. In this account the creation appears to be described as having been accomplished in six days. It begins in these words: 'At that time the heavens above named not a name, nor did the earth below record one; yea, the ocean was their first creator, the flood of the deep (Tiamat) was she who bore them all. Their waters were embosomed in one place, and the clouds (?) were not collected, the plant was still ungrown. At that time the gods had not issued forth, any one of them; by no name were they recorded, no destiny (had they fixed). Then the (great) gods were made; Lakhmu and Lakhamu issued forth the first. They grew up.... Next were made the host of heaven and earth. The time was long, (and then) the gods Anu, (Bel, and Ea were born of) the host of heaven and earth.' The rest of the account is lost, and it is not until we come to the fifth tablet of the series, which describes the appointment of the heavenly bodies, that the narrative is again preserved. Here we are told that the creator, who seems to have been Ea, 'made the stations of the great gods, even the stars, fixing the places of the principal stars like ... He ordered the year, setting over it the decans; yea, he established three stars for each of the twelve months.' It will be remembered that, according to Genesis, the appointment of the heavenly bodies to guide and govern the seasons was the work of the fourth day, and since the work is described in the fifth tablet or book of the Assyrian account, while the first tablet describes the condition of the universe before the creation was begun, it becomes probable that the Assyrians also knew that the work was performed on the fourth day. The next tablet states that 'at that time the gods in their assembly created (the living creatures). They made the mighty (animals). They caused the living beings to come forth, the cattle of the field, the beast of the field, and the creeping thing.' Unfortunately the rest of the narrative is in too mutilated a condition for a translation to be possible, and the part which describes the creation of man has not yet been recovered among the ruins of the library of Nineveh. The Chaldean account of the Deluge was discovered by Mr. George Smith, and its close resemblance to the account in Genesis is well known. Those who wish to see a translation of it, according to the latest researches, will find one in the pages of 'Fresh Light from the Ancient Monuments.' The account was introduced as an episode into the eleventh book of the great Babylonian epic of Gisdhubar, and appears to be the amalgamation of two older poems on the subject. The story of the Deluge, in fact, was a favourite theme among the Babylonians, and we have fragments of at least two other versions of it, neither of which, however, agree so remarkably with the Biblical narrative as does the version discovered by Mr. Smith. Apart from the profound difference caused by the polytheistic character of the Chaldean account, and the monotheism of the Scriptural narrative, it is only in details that the two accounts vary from one another. Thus, the vessel in which Xisuthros, the Chaldean Noah, sails, is a ship, guided by a steersman, and not an ark, and others besides his own family are described as being admitted into it. So, too, the period of time during which the flood was at its height is said to have been seven days only, while, beside the raven and the dove, Xisuthros is stated to have sent out a third bird, the swallow, in order to determine how far the waters had subsided. The Chaldean ark rested, moreover, on Rowandiz, the highest of the mountains of Eastern Kurdistan, and the peak whereon Accadian mythology imagined the heavens to be supported, and not on the northern or Armenian continuation of the range. Babylonian tradition, too, had fused into one Noah and Enoch, Xisuthros being represented as translated to the land of immortality immediately after his descent from the ark and his sacrifice to the gods. It is noticeable that the Chaldean account agrees with that of the Bible in one remarkable respect, in which it differs from almost all the other traditions of the Deluge found throughout the world. This is in its ascribing the cause of the Deluge to the wickedness of mankind. It was sent as a punishment for sin. As might have been expected, the Babylonians and Assyrians knew of the building of the Tower of Babel, and the dispersion of mankind. Men had 'turned against the father of all the gods,' under a leader the thoughts of whose heart 'were evil.' At Babylon they began to erect 'a mound,' or hill-like tower, but the winds destroyed it in the night, and Anu 'confounded great and small on the mound,' as well as their 'speech,' and 'made strange their counsel.' All this was supposed to have taken place at the time of the autumnal equinox, and it is possible that the name of the rebel leader, which is lost, was EtŠna. At all events the demi-god EtŠna played a conspicuous part in the early historical mythology of Babylonia, like two other famous divine kings, Ner and Dun, and a fragment describes him as having built a city of brick. However this may be, EtŠna is the Babylonian Titan of Greek writers, who, with PromÍtheus and Ogygos, made war against the gods. If we sum up the character of Assyrian religion, we shall find it characterised by curious contrasts. On the one hand we shall find it grossly polytheistic, believing in 'lords many and gods many,' and admitting not only gods and demi-gods, and even deified men, but the multitudinous spirits, 'the host of heaven and earth,' who were classed together as the '300 spirits of heaven and the 600 spirits of earth.' Some of these were beneficent, others hostile, to man. In addition to this vast army of divine powers, the Assyrian offered worship also to the heavenly bodies, and to the spirits of rivers and mountains. He even set up stones or 'Beth-els,' so called because they were imagined to be veritable 'houses of god,' wherein the godhead dwelt, and over these he poured out libations of oil and wine. Yet, on the other hand, with all this gross polytheism, there was a strong tendency to monotheism. The supreme god, Assur, is often spoken of in language which at first sight seems monotheistic: to him the Assyrian monarchs ascribe their victories, and in his name they make war against the unbeliever. A similar inconsistency prevailed in the character of Assyrian worship itself. There was much in it which commands our admiration: the Assyrian confessed his sins to his gods, he begged for their pardon and help, he allowed nothing to interfere with what he conceived to be his religious duties. With all this, his worship of Istar was stained with the foulest excesses—excesses, too, indulged in, like those of the Phœnicians, in the name and for the sake of religion. Much of this inconsistency may be explained by the history of his religious ideas. As we have seen, a large part of them was derived from a non-Semitic population, the primitive inhabitants of Babylonia, under whose influence the Semitic Babylonians had come at a time when they still lacked nearly all the elements of culture. The result was a form of creed in which the old Accadian faith was bodily taken over by an alien race, but at the same time profoundly modified. It was Accadian religion interpreted by the Semitic mind and belief. Baal-worship, which saw the Sun-god everywhere under an infinite variety of manifestations, waged a constant struggle with the conceptions of the borrowed creed, but never overcame them altogether. The gods and spirits of the Accadians remained to the last, although permeated and overlaid with the worship of the Semitic Sun-god. As time went on, new religious elements were introduced, and Assyro-Babylonian religion underwent new phases, while in Assyria itself the deified state in the person of the god Assur tended to absorb the religious cult and aspirations of the people. The higher minds of the nation struggled now and again towards the conception of one supreme God and of a purer form of faith, but the dead weight of polytheistic beliefs and practices prevented them from ever really reaching it. In the best examples of their religious literature we constantly fall across expressions and ideas which show how wide was the gulf that separated them from that kindred people of Israel to whom the oracles of God were revealed.

|

|

|

|

|

3) Confer 2 Kings xvii. 30. 4) A. V. 'congregation.' 5) A. V. 'sides.' |

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD