By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 7 - Assyria - Its Princes, Priests, and People

By A. H. Sayce M.A.

Chapter 5

|

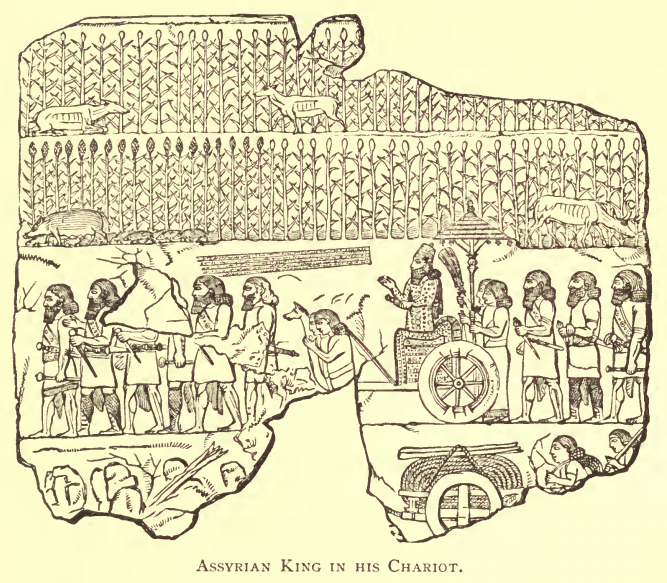

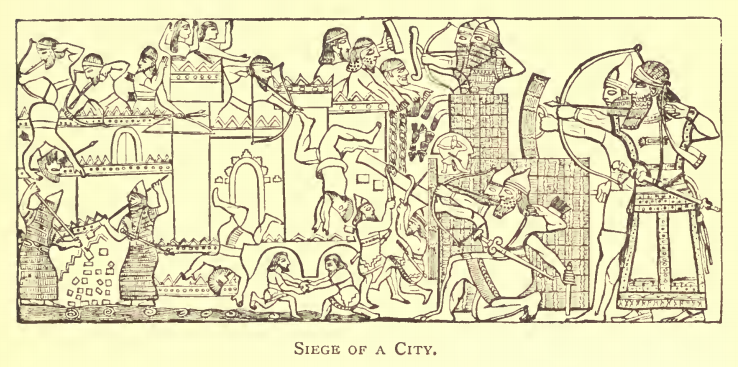

Manners and Customs; Trade and Government The monuments of Assyria do not give us the same assistance as those of Egypt in learning about the manners and customs of its inhabitants. We find there no tombs whose pictured walls set before us the daily life and doings of the people. We have to acquire our knowledge from the bas-reliefs of the royal palaces, which represent to us rather the pomp of the court and the conquest of foreign nations than scenes taken from ordinary Assyrian life. It is only incidentally that the manners and customs of the lower classes are depicted. It is true that we can learn a good deal from the contract-tablets and other kinds of what may be called the private literature of Babylonia and Assyria. At present, however, but a small portion of these has been examined, and a literature can never paint so fully and distinctly the manners and customs of the day as the picture or sculpture on the wall. It is only in times comparatively modern that the novelist has sought to give a faithful portrait of the life of the peasant and artisan. The dress of the upper classes in Assyria did not differ essentially from that of the well-to-do Oriental of to-day. In time of peace the king was dressed in a robe which reached to the ankles, bound round the waist with a broad belt, while a mantle was thrown over his shoulders, and a tiara or fillet was worn on his head. The tiara sometimes resembled the triple tiara of the Pope, sometimes was of cone-like shape, and the fillet was furnished with two long bandelettes which fell down behind. The robe and mantle were alike richly embroidered and edged with fringes. The arms were left bare, except in so far as they could be covered by the mantle, and a heavy pair of bracelets encircled each, the workmanship of the jewelry being similar to that of the chain which was worn round the neck. The feet were shod with sandals which had a raised part behind to protect the heels, and they were fastened to the feet by a ring through which the great toe passed, and a latchet over the instep. Sandals of precisely the same character are still used in Mesopotamia. The monarch's dress in war was similar to that used in time of peace, except that he carried a belt for daggers, while a fringed apron took the place of the mantle. Boots laced in front were also sometimes substituted for the sandals. The upper classes, and more especially the officials about court, wore a costume similar to that of the king, only of course, less rich and costly. In all cases they were distinguished by the long fringed sleeveless robe which descended to the ankles. The dress of the soldiers and of the common people generally was quite different. It consisted only of the tunic, over which in all probability the long robe of the wealthy was worn, and which did not quite reach the knees. Sometimes a sort of jacket was put on above it, and, in a few instances, a simple kilt seems to take its place. The kilt was frequently worn under the tunic, which was fastened round the waist by a girdle or sword-belt. The arms, legs, and feet, were bare. Some of the soldiers, however, wore sandals, and others, more particularly the cavalry, wore boots, which were laced in front, and came half way up the leg. The upper part of the legs was occasionally protected by drawers of leather or chain-armour, and we even find tunics made of the same materials. Helmets were also employed, but the common soldier usually covered his head with a simple skull-cap. The dress of the women consisted of a long tunic and mantle, and a fillet for confining the hair. The king and his officers rode in chariots even when on a campaign. In crossing mountains the chariots often had to be carried on the shoulders of men or animals, their wheels being sometimes first taken off for the purpose. The chariot was large enough to contain not only the king but an umbrella-bearer and a charioteer as well. The latter held the reins in both hands, each rein being single and fastened to either side of a snaffle-like bit. When in the field the royal chariot was followed by a bow-bearer and a quiver-bearer, as well as by led horses, intended to assist the monarch to escape, should the fortune of battle turn against him. The chariot was drawn by two horses, a third horse being usually attached to it by a thong in order to take the place of one of the other two if an accident occurred. Assyrian King in his Chariot Beside the chariots the army was accompanied by a corps of cavalry. In the time of the first Assyrian Empire the cavalry-soldier rode on the bare back of the horse, with his knees crouched up in front of him; subsequently saddles were introduced, though not stirrups. The cavalry was divided into two corps—the heavy and the light-armed. The latter were armed only with the bow and arrow and a guard for the wrist, and were chiefly employed in skirmishing. Most of the archers, however, belonged to the infantry. The Assyrians were particularly skilled in the use of the bow, and their superiority in war was probably in great measure due to it. Besides the bow they employed the spear, the short dagger or dirk, and the sword, which was of two kinds. The ordinary kind was long and straight, the less usual kind being curved, like a scimetar. For defence, round shields, of no great size, were carried. Only the king and the chief nobles were allowed the luxury of a tent. The common soldier had to sleep on the ground, wrapped up in a blanket or plaid. The tent was probably of felt, and had an opening in the centre through which the smoke of a fire might escape. Not only, however, was a sleeping-tent carried for the king, a cooking-tent was carried also. So also was the royal chair, called a nimedu, on which the monarch sat when stationary in camp. The chair may be seen in the bas-relief, now in the British Museum, which represents Sennacherib sitting upon it in front of the captured town of Lachish. Above is a short inscription which tells us that 'Sennacherib, the king of legions, the king of Assyria, sat on an upright throne, and the spoil of the city of Lachish passed before him.' There were various means for assaulting a hostile town. Sometimes scaling-ladders were used, sometimes the walls were undermined with crowbars and pickaxes; sometimes a battering-ram was employed armed with one or two spear-like projections; sometimes fire was applied to the enemy's gates. Other engines are mentioned in the inscriptions, but as they have not been found depicted on the monuments it is difficult to identify them. Siege of a City The barbarities which followed the capture of a town would be almost incredible, were they not a subject of boast in the inscriptions which record them. Assur-natsir-pal's cruelties were especially revolting. Pyramids of human heads marked the path of the conqueror; boys and girls were burned alive or reserved for a worse fate; men were impaled, flayed alive, blinded, or deprived of their hands and feet, of their ears and noses, while the women and children were carried into slavery, the captured city plundered and reduced to ashes, and the trees in its neighbourhood cut down. During the second Assyrian Empire warfare was a little more humane, but the most horrible tortures were still exercised upon the vanquished. How deeply-seated was the thirst for blood and vengeance on an enemy is exemplified in a bas-relief which represents Assur-bani-pal and his queen feasting in their garden while the head of the conquered Elamite king hangs from a tree above. The Assyrians made use of chairs, tables, and couches. A piece of sculpture from Khorsabad introduces us to a scene in which the priests of the king are seated, two on a chair on either side of a four-legged table. Their sandals are removed, as was the custom among the Greeks when eating. In the luxurious days of Assur-bani-pal the couch seems to have partially taken the place of the chair, since in the scene alluded to above the king is depicted reclining, though the queen sits in a chair by his side. The number of different kinds of food mentioned in the inscriptions seems to imply that the Assyrians were fond of good living. The common people, it is true, lived mostly on bread, fruit, and vegetables; but the monuments show us soldiers engaged in slaughtering and cooking oxen and sheep. Wine was the usual beverage at a banquet, and the Assyrians appear to have resembled the Persians in their indulgence in it. Various sorts of wine are enumerated in the inscriptions, most of which were imported from abroad. Among the most highly prized was the wine of Khilbun or Helbon, which is mentioned in Ezek. xxvii. 18, and was grown near Damascus at a village still called Halbūn. Besides grape-wine, palm-wine, made from dates, was brought from Babylon, and beer, milk, cream, butter or ghee, and oil, were all much used. At a feast the wine was ladled out of a large vase into cups, which were then presented to the guests. The table was ornamented with flowers, and musicians were hired to amuse the banqueters. No less than seven or eight different musical instruments were known, among them the harp, the lyre, and the tambourine. The lyre seems to have been specially employed at feasts, and the harp for the performance of sacred music. The instrumental music was at times accompanied by the voice, and bands of musicians celebrated the triumphant return of the king from war. Polygamy was permitted—at all events to the monarch—and the palace was accordingly guarded by a whole army of eunuchs. They were generally in attendance on the sovereign, like the scribes whose offices were continually needed in both peace and war. Another attendant must not be forgotten—the servant who stood behind the king armed with a fly-flap, and was almost a necessity in hot weather. Considering the number of captives carried away every year to Assyria in the successful campaigns of its rulers, slaves must have been very plentiful in Nineveh. Indeed, after the Arabian campaign of Assur-bani-pal we are told that a camel was sold for half a shekel of silver, and that a man was worth a correspondingly small sum. Next to hunting men the chief employment and delight of an Assyrian king was to hunt wild beasts. Tiglath-Pileser I had hunted elephants in the land of the Hittites, as the Egyptian Pharaohs had done before him; subsequently the extinction of the elephant in Western Asia caused his successors to content themselves with lesser game. The reem or wild bull and the lion became their favourite sport, smaller animals like the gazelle, the hare, and the wild ass being left to their subjects to pursue. It was not until the reign of Assur-bani-pal that the lion-hunt ceased to be a dangerous and exciting pastime. With Esar-haddon, however, the old race of warrior kings had come to an end, and the new king introduced a new style of sport. The lions were now caught and kept in cages, until they were turned out for a royal battue. As they had to be whipped into activity, neither the monarch nor his companions could have run much risk of being harmed. The Assyrians were not an agricultural people like the Babylonians. Nevertheless, the kings had their paradises or parks, and the wealthier classes their gardens or shrubberies. The garden was planted with trees rather than with flowers or herbs, and afforded a shady retreat during the summer months. Tiglath-Pileser I had even established a sort of botanical garden, in which he tried to acclimatise some of the trees he had met with in his campaigns. He tells us of it: 'As for the cedar, the likkarin tree, and the almug, from the countries I have conquered, these trees, which none of the kings my fathers that were before me had planted, I took, and in the gardens of my land I planted, and by the name of garden I called them; whatsoever in my land there was not I took, and I established the gardens of Assyria.' The gardens were abundantly watered from the river or canal, by the side of which they were usually planted. Summer-houses were built in the midst of them, and as early as the time of Sennacherib we meet with a 'hanging garden,' grown on the roof of a building. Fishing was carried on with a line merely, and without a rod. The fisherman sat on the bank, or else swam in the water, supporting himself on an inflated skin. These inflated skins were largely used in warfare for conveying troops and animals across a stream. The chief officers, along with their chariots and commissariat, were ferried across in boats, but the soldiers had to strip, and with the help of the skins convey themselves, their arms, the horses, and other baggage to the opposite bank. At times a pontoon-bridge of boats was constructed, at other times the Assyrian army was fortunate enough to meet with bridges of stone or wood. In fact, such bridges existed on all the main roads which it traversed. Western Asia was more thickly populated then than is at present the case, and the roads were not only more numerous than they are to-day, but better kept. Hence the ease and rapidity with which large bodies of men were moved by the Assyrian kings from one part of Asia to another. Where a road did not already exist, it was made by the advancing army, timber being cleared and a highway thrown up for the purpose. As road-makers the Assyrians seem to have anticipated the Romans. Both their military and their trading instincts led them in this direction. It was only when they came to the water that their career was checked. Excellent as they were as soldiers, they never became sailors. The boats of the Tigris and Euphrates were either rafts or circular coracles of skins stretched on a wooden framework. When Sennacherib wished to attack the Chaldeans of Beth-Yagina in their place of refuge on the Persian Gulf, he had to transport Phœnicians from the west to build his galleys, and to navigate them afterwards. It was the Babylonians 'whose cry was in their ships;' the Assyrians fought and traded on shore. It was not until the rise of the Second Assyrian Empire that the trade of Assyria became important. The earlier kings had gone forth to war for the sake of booty or out of mere caprice; Tiglath-Pileser II and his successors aimed at getting the commerce of the world into the hands of their own subjects. The fall of Carchemish and the overthrow of the Phœnician cities enabled them to carry out their design. Nineveh became a busy centre of trade, from whence caravans went and returned north and south, east and west. The old Hittite standard of weight, called 'the maneh of Carchemish' by the Assyrians, was made the ordinary legal standard, and Aramaic became the common language of trade. Not unfrequently an Aramaic docket accompanies an Assyrian contract tablet, stating briefly what were its contents and the names of the chief contracting parties. These contract tablets have to do with the sale and lease of houses, slaves, and other property, as well as with the amount of interest to be paid upon loans. We learn from them that the rate of interest was usually as low as four per cent., and when objects like bronze were borrowed as three per cent. House property naturally varied in value. A house sold at Nineveh on the sixteenth of Sivan or May, B.C. 692, fetched one maneh of silver or £9, the average price of a slave. Thus, three Israelites, as Dr. Oppert believes, were sold by a Phœnician on the twentieth of Ab or July, B.C. 709, for £27, retractation or annulment of the sale being subject to a penalty of about £230, part of which was to go to the temple of Istar of Arbela. Twenty years later, however, as many as seven slaves, among them an Israelite, Hoshea, and his two wives, were sold for the same price, while we find a girl handed over by her parents to an Egyptian lady Nitōkris, who wished to marry her to her son Takhos, for the small sum of £2 10s. The last deed of sale, by the way, proves that wives in Assyria could sometimes be bought. All deeds and contracts were signed and sealed in the presence of a number of attesting witnesses, who attached their seals, or, if they were too poor to possess any, their nail-marks, to the documents. It was then enclosed in an outer coating of clay, on which an abstract of its contents was given. Sometimes a further document on papyrus was fastened to it by means of a string. It was only in the case of the monarch himself that the signatures of attesting witnesses were dispensed with. The British Museum possesses a sort of private will made by Sennacherib in favour of Esar-haddon, when the latter was not as yet heir-apparent to the throne. In this no witnesses are mentioned, and it is considered sufficient that the document should be lodged in the imperial archives. It runs as follows: 'I, Sennacherib, king of legions, king of Assyria, bequeathe armlets of gold, quantities of ivory, a platter of gold, ornaments and chains for the neck, all these beautiful things of which there are heaps, and three sorts of precious stones, 1-1/2 manehs and 2-1/2 shekels in weight, to Esar-haddon, my son, whose name was afterwards changed to Assur-sar-illik-pal by my wish. I have deposited the treasure in the house of Amuk. Thine is the kingdom, O Nebo, our light!' Payments, it must be remembered, were still made by weight, coined money not having been introduced until after the time of Nebuchadnezzar. The business-like character of the trading community of Nineveh will best be gathered from the documents themselves which have been left to us. It will, therefore, not be out of place to add here translations of some of the contract tablets:—

Then follow two lines and a half of Aramaic, the first of which contains the name of Mannu-ki-Arbela.

It will be noticed that the Israelitish witnesses to the last deed of sale, Pekah and Nadabiah, hold public offices, though the exact nature of them is at present unknown. We may conclude from this that some of the Samaritan captives were allowed to live in Nineveh, and so far from being in a condition of slavery were able to be in the service of the state. Among the earliest known examples of Israelitish or Jewish writing are seals which probably belong to a period anterior to the Babylonish Exile, and have been found at Diarbekr and other places in the neighbourhood of the Tigris and Euphrates. It is also possible that the great banking firm of Egibi, which flourished at Babylon from the time of Sennacherib and Esar-haddon to that of Darius and Xerxes, and carried on business transactions as extensive as those of the Rothschilds of to-day, was of Israelitish origin. At all events the name Egibi is not Babylonian, while it is a very exact Babylonian transcript of the Biblical name Jacob. The contract tablets throw a good deal of light upon Assyrian law. In its main outlines it did not differ much from our own. Precedents and previous decisions seem to have been held in as high estimation as among our own lawyers. The king was the supreme court of appeal, and copies exist of private petitions preferred to him on a variety of matters. Judges were appointed under the king, and prisons were established in the towns. An old Babylonian code of moral precepts addressed to princes denounces the ruler who listens to the evil advice of his courtiers, and does not deliver judgment 'according to the statutes,' 'the law-book,' and 'the writing of the god Ea.' The earliest existing code of laws is one which goes back to the Accadian epoch, and contains an express enactment for protecting the slave against his master. How far it was made the basis of subsequent Semitic legislation it is difficult to say; in one respect, at all events, it differed considerably from the law which followed it. This was in the position it assigned to women. Among the Accadians, the woman was the equal of man; in fact, she ranked before the husband in matters relating to the family; whereas among the Semites she was degraded to a very inferior rank. It is curious to find the Semitic translator of an Accadian text invariably changing the order in which the words for man and woman, male and female occur in the original. In the Accadian the order is 'woman and man,' in the Assyro-Babylonian translation, 'man and woman.' The high-roads were placed under the charge of commissioners, and in Babylonia, where brick-making was an important occupation, the brick-yards as well. Certain of the taxes, which were raised alike from citizens and aliens, were devoted to the maintenance of them. Unfortunately we know but little at present of the precise way in which the taxes were levied, and the principle on which they were distributed among the various classes of the population. In Babylonia, however, the tenant does not seem to have paid much to the government, since we are told of him that after handing over one-third of the produce of an estate to his landlord, he might keep the rest of it for himself. There is no hint that any portion of it was distrained for the state. As in modern Turkey, the imperial exchequer after the time of Tiglath-Pileser II was supplied by fixed contributions from the separate provinces and large towns. Thus Nineveh itself was assessed at thirty talents. The best way, however, of giving an idea of the assessment is by a translation of the few fragments of the assessment lists of the Second Empire which have been preserved to us.

In spite of the fragmentary character of these lists, and the difficulty of understanding them perfectly in consequence of their brevity and the omission of prepositions, we may nevertheless glean from them a fair idea of the method in which the imperial exchequer of Assyria was replenished, and the objects to which the taxes and tribute were devoted. A considerable amount must have gone to the great army of officials by whom the Second Empire was administered. 'The great king,' it was true, was autocratic like the Russian Czar, but like the Russian Czar he was also controlled by a bureaucracy which managed the government under him. In military matters alone he was supreme, though even here two commanders-in-chief stood at his side, ready to take his place in the command of the troops whenever age or disinclination detained him at home. The lists of Assyrian officials which we possess are very lengthy, and their titles seem almost endless. At the head came the two commanders-in-chief, the Turtannu or Tartan of the right, and the Turtannu of the left, doubtless so called from their position on the right and left of the king. Next to them were the Chamberlain or superintendent of the singing men and women, and then after five other officials whose posts are obscure, the 'Rab-sak' or 'Rab-shakeh.' His title means literally 'chief of the princes,' and he corresponded to the Vizier or Prime Minister of the Turkish Empire. Among other public offices we may notice that of the astronomer, who was supported by the state like the rest, and who ranked immediately after the 'superintendent of the camel-stables.' The latter again was inferior in rank to the 'captain of the watch,' 'the captain of fifty,' 'the overseer of the vineyards,' and 'the overseer of the quays.' Such, then, was the constitution of the great Assyrian Empire, which first endeavoured to organise Western Asia into a single homogeneous whole, and in effecting its purpose cared neither for justice nor for humanity. Nineveh was 'full of lies and robbery,' but it was God's instrument in chastising His chosen people, and in preparing the way for the ages that were to come, and for a while, therefore, it was allowed to 'make the earth empty' and 'waste.' But the day came when its work was accomplished, and the measure of its iniquity was full. Nineveh, 'the bloody city,' fell, never to rise again and the doom pronounced by Nahum was fulfilled. For centuries the very site of the imperial city remained unknown, and the traveller and historian alike put the vain question: 'Where is the dwelling of the lions, and the feeding-place of the young lions, where the lion, even the old lion, walked, and the lion's whelp, and none made them afraid?'

|

|

|

|

|

7) Now Shamameh, south-west Arbela 8) The Kue or Kuans inhabited the northern and eastern shores of the Gulf of Antioch. M. Franēois Lenormant has ingeniously suggested that in 1 Kings x. 28, we ought to read (with a slight change of vowel punctuation), 'And Solomon had horses brought out of Egypt, and out of Kue the king's merchants received a drove at a price.'

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD