By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 12 - The Hittites: The Story of a Forgotten Empire

A. H. Sayce, LL.D.

Chapter 2

THE HITTITES ON THE MONUMENTS OF EGYPT AND ASSYRIA.In the preceding chapter we have seen what the Bible has to tell us about 'the children of Heth.' They were an important people in the north of Syria who were ruled by 'kings' in the days of Solomon, and whose power was formidable to their Syrian neighbours. But there was also a branch of them established in the extreme south of Palestine, where they inhabited the mountains along with the Amorites, and had taken a share in the foundation of Jerusalem. It was from one of the latter, Ephron the son of Zohar, that Abraham had purchased the cave of Machpelah at Hebron; and one of the wives of Esau was of Hittite descent. In later times Uriah the Hittite was one of the chief officers of David, and his wife Bath-sheba was not only the mother of Solomon, but also the distant ancestress of Christ. For us, therefore, these Hittites of Judśa have a very special and peculiar interest. The decipherment of the inscriptions of Egypt and Assyria has thrown a new light upon their origin and history, and shown that the race to which they belonged once played a leading part in the history of the civilised East. On the Egyptian monuments they are called Kheta (or better Khata), on those of Assyria Khatt‚ or Khate, both words being exact equivalents of the Hebrew Kheth and Khitti. The Kheta or Hittites first appear upon the scene in the time of the Eighteenth Egyptian Dynasty. The foreign rule of the Hyksos or Shepherd princes had been overthrown, Egypt had recovered its independence, and its kings determined to retaliate upon Asia the sufferings brought upon their own country by the Asiatic invader. The war, which commenced with driving the Asiatic out of the Delta, ended by attacking him in his own lands of Palestine and Syria. Thothmes I. (about B.C. 1600) marched to the banks of the Euphrates and set up 'the boundary of the empire' in the country of Naharina. Naharina was the Biblical Aram Naharaim or 'Syria of the two rivers,' better known, perhaps, as Mesopotamia, and its situation has been ascertained by recent discoveries. It was the district called Mitanni by the Assyrians, who describe it as being 'in front of the land of the Hittites,' on the eastern bank of the Euphrates, between Carchemish and the mouth of the river Balikh. In the age of Thothmes I., it was the leading state in Western Asia. The Hittites had not as yet made themselves formidable, and the most dangerous enemy the Egyptian monarch was called upon to face were the people over whom Chushan-risha-thaim was king in later days (Judg. iii. 8). It is not until the reign of his son, Thothmes III., that the Hittites come to the front. They are distinguished as 'Great' and 'Little,' the latter name perhaps denoting the Hittites of the south of Judah. However this may be, Thothmes received tribute from 'the king of the great land of the Kheta,' which consisted of gold, negro-slaves, men-servants and maid-servants, oxen and servants. Whether the Hittites were as yet in possession of Kadesh we do not know. If they were, they would have taken part in the struggle against the Egyptians which took place around the walls of Megiddo, and was decided in favour of Thothmes only after a long series of campaigns. Before Thothmes died, he had made Egypt mistress of Palestine and Syria as far as the banks of the Euphrates and the land of Naharina. One of the bravest of his captains tells us on the walls of his tomb how he had captured prisoners in the neighbourhood of Aleppo, and had waded through the waters of the Euphrates when his master assaulted the mighty Hittite fortress of Carchemish. Kadesh on the Orontes had already fallen, and for a time all Western Asia did homage to the Egyptian monarch, even the king of Assyria sending him presents and courting, as it would seem, his alliance. The Egyptian empire touched the land of Naharina on the east and the 'great land of the Hittites' on the north. But neighbours so powerful could not remain long at peace. A fragmentary inscription records that the first campaign of Thothmes IV., the grandson of Thothmes III., was directed against the Hittites, and Amenophis III., the son and successor of Thothmes IV., found it necessary to support himself by entering into matrimonial alliance with the king of Naharina. The marriage had strange consequences for Egypt. The new queen brought with her not only a foreign name and foreign customs, but a foreign faith as well. She refused to worship Amun of Thebes and the other gods of Egypt, and clung to the religion of her fathers, whose supreme object of adoration was the solar disk. The Hittite monuments themselves bear witness to the prevalence of this worship in Northern Syria. The winged solar disk appears above the figure of a king which has been brought from Birejik on the Euphrates to the British Museum; and even at Boghaz Keui, far away in Northern Asia Minor, the winged solar disk has been carved by Hittite sculptors upon the rock. Amenophis IV., the son of Amenophis III., was educated in the faith of his mother, and after his accession to the throne endeavoured to impose the new creed upon his unwilling subjects. The powerful priesthood of Thebes withstood him for a while, but at last he assumed the name of Khu-n-Aten, 'the refulgence of the solar disk,' and quitting Thebes and its ancient temples he built himself a new capital dedicated to the new divinity. It stood on the eastern bank of the Nile, to the north of Assiout, and its long line of ruins is now known to the natives under the name of Tel el-Amarna. The city was filled with the adherents of the new creed, and their tombs are yet to be found in the cliffs that enclose the desert on the east. Its existence, however, was of no long duration. After the death of Khu-n-Aten, 'the heretic king,' his throne was occupied by one or two princes who had embraced his faith; but their reigns were brief, and they were succeeded by a monarch who returned once more to the religion of his forefathers. The capital of Khu-n-Aten was deserted, and the objects found upon its site show that it was never again inhabited. Among its ruins a discovery has recently been made which casts an unexpected light upon the history of the Oriental world in the century before the Exodus. A large collection of clay tablets has been found, similar to those disinterred from the mounds of Nineveh and Babylonia, and like the latter inscribed in cuneiform characters and in the Assyro-Babylonian language. They consist for the most part of letters and despatches sent to Khu-n-Aten and his father, Amenophis III., by the governors and rulers of Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia and Babylonia, and they prove that at that time Babylonian was the international language, and the complicated cuneiform system of writing the common means of intercourse, of the educated world. Many of them were transferred by Khu-n-Aten from the royal archives of Thebes to his new city at Tel el-Amarna; the rest were received and stored up after the new city had been built. We learn from them that the Hittites were already pressing southward, and were causing serious alarm to the governors and allies of the Egyptian king. One of the tablets is a despatch from Northern Syria, praying the Egyptian monarch to send assistance against them as soon as possible. The 'heresy' of Khu-n-Aten brought trouble and disunion into Egypt, and his immediate successors seem to have been forced to retire from Syria. So far from being able to aid their allies, the Egyptian generals found themselves no match for the Hittite armies. Ramses I., the founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty, was compelled to conclude a treaty, defensive and offensive, with the Hittite king Saplel, and thus to recognise that Hittite power was on an equality with that of Egypt. From this time forward it becomes possible to speak of a Hittite empire. Kadesh was once more in Hittite hands, and the influence formerly enjoyed by Egypt in Palestine and Syria was now enjoyed by its rival. The rude mountaineers of the Taurus had descended into the fertile plains of the south, interrupting the intercourse between Babylonia and Canaan, and superseding the cuneiform characters of Chaldśa by their own hieroglyphic writing. From henceforth the Babylonian language ceased to be the language of diplomacy and education. With Seti I., the son and successor of Ramses, the power of Egypt again revived. He drove the Beduin and other marauders across the frontiers of the desert and pushed the war into Syria itself. The cities of the Philistines again received Egyptian garrisons; Seti marched his armies as far as the Orontes, fell suddenly upon Kadesh and took it by storm. The war was now begun between Egypt and the Hittites, which lasted for the next half-century. It left Egypt utterly exhausted, and, in spite of the vainglorious boasts of its scribes and poets, glad to make a peace which virtually handed over to her rivals the possession of Asia Minor. But at first success waited on the arms of Seti. He led his armies once more to the Euphrates and the borders of Naharina, and compelled Mautal, the Hittite monarch, to sue for peace. The natives of the Lebanon received him with acclamations, and cut down their cedars for his ships on the Nile. When Seti died, however, the Hittites were again in possession of Kadesh, and war had broken out between them and his son Ramses II. The long reign of Ramses II. was a ceaseless struggle against his formidable foes. The war was waged with varying success. Sometimes victory inclined to the Egyptians, sometimes to their Hittite enemies. Its chief result was to bring ruin and disaster upon the cities of the Canaanites. Their land was devastated by the hostile armies which traversed it; their towns were sacked, now by the Hittite invaders from the north, now by the soldiers of Ramses from the south. It was little wonder that their inhabitants fled to island fastnesses like Tyre, deserting the city on the mainland, which an Egyptian traveller of the age of Ramses tells us had been burnt not long before. We can understand now why they offered so slight a resistance to the invading Israelites. The Exodus took place shortly after the death of Ramses II., the Pharaoh of the oppression; and when Joshua entered Palestine he found there a disunited people and a country exhausted by the long and terrible wars of the preceding century. The way had been prepared by the Hittites for the Israelitish conquest of Canaan. Pentaur, a sort of Egyptian poet laureate, has left us an epic which records the heroic deeds of Ramses in his first campaign against the Hittites. The actual event which gave occasion to it was an act of bravery performed by the Egyptian monarch before the walls of Kadesh; but the poet has transformed him into a hero capable of superhuman deeds, and has thus produced an epic poem which reminds us of the Greek Iliad. Its details, however, afford a welcome insight into the history of the time, and show to what a height of power the Hittite empire had advanced. Its king could summon to his aid vassal-allies not only from Syria, but from the distant regions of Asia Minor as well. The merchants of Carchemish, the islanders of Arvad, acknowledged his supremacy along with the Dardanians of the Troad and the Mśonians of Lydia. The Hittite empire was already a reality, extending from the banks of the Euphrates to the shores of the ∆gean, and including both the cultured Semites of Syria and the rude barbarians of the Greek seas. It was in the fifth year of the reign of Ramses (B. C. 1383) that the event occurred which was celebrated by the Egyptian Homer. The Egyptian armies had advanced to the Orontes and the neighbourhood of Kadesh. There two Beduin spies were captured, who averred that the Hittite king was far away in the north with his forces, encamped at Aleppo. But the intelligence was false. The Hittites and their allies, multitudinous as the sand on the sea-shore, were really lying in ambush hard by. In their train were the soldiers of Naharina, of the Dardanians and of Mysia, along with numberless other peoples who now owned the Hittite sway. The Hittite monarch 'had left no people on his road without bringing them with him. Their number was endless; nothing like it had ever been before. They covered mountains and valleys like grasshoppers for their number. He had not left silver or gold with his people; he had taken away all their goods and possessions to give it to the people who accompanied him to the war.' The whole host was concealed in ambush on the north-west side of Kadesh. Suddenly they arose and fell upon the terrified Egyptians by the waters of the Lake of the Amorites, the modern Lake of Homs. The chariots and horses charged 'the legion of Ra-Hormakhis,' and 'foot and horse gave way before them.' The news was carried to the Pharaoh. 'He arose like his father Month, he grasped his weapons, and put on his armour like Baal.' His steed 'Victory in Thebes' bore him in his chariot into the midst of the foe. Then he looked behind him, and behold he was alone. The bravest heroes of the Hittite host beset his retreat, and 2500 hostile chariots were around him. He was abandoned in the midst of the enemy: not a prince, not a captain was with him. Then in his extreme need the Pharaoh called upon his god Amun. 'Where art thou, my father Amun? If this means that the father has forgotten his son, have I done anything without thy knowledge, or have I not gone and followed the precepts of thy mouth? Never were the precepts of thy mouth transgressed, nor have I broken thy commandments in any respect. Sovran lord of Egypt, who makest the peoples that withstand thee to bow down, what are these people of Asia to thy heart? Amun brings them low who know not God.... Behold now, Amun, I am in the midst of many unknown peoples in great number. All have united themselves, and I am all alone: no other is with me; my warriors and my charioteers have deserted me. I called to them, and not one of them heard my voice.' The petition of Ramses was heard. Amun 'reached out his hand,' and declared that he was come to help the Pharaoh against his foes. Then Ramses was inspired with supernatural strength. 'I hurled,' he is made to say, 'the dart with my right hand, I fought with my left hand. I was like Baal in his hour before their sight. I had found 2500 chariots; I was in the midst of them; but they were dashed in pieces before my horses.' The ground was covered with the slain, and the Hittite king fled in terror. His princes again gathered round the Pharaoh, and again Ramses scattered them in a moment. Six times did he charge the Hittite host, and six times they broke and were slaughtered. The strength of Baal was 'in all the limbs' of the Egyptian king. Now at last his servants came to his aid. But the victory had already been won, and all that remained was for the Pharaoh to upbraid his army for their cowardice and sloth. 'Have I not given what is good to each of you,' he exclaims, 'that ye have left me, so that I was alone in the midst of hostile hosts? Forsaken by you, my life was in peril, and you breathed tranquilly, and I was alone. Could you not have said in your hearts that I was a rampart of iron to you?' It was the horses of the royal chariot and not the troops who deserved reward, and who would obtain it when the king arrived safely home. So Ramses 'returned in victory and strength; he had smitten hundreds of thousands all together in one place with his arm.' At daybreak the following morning he desired to renew the conflict. The serpent that glowed on the front of his diadem 'spat fire' in the face of his enemies. They were overawed by the deeds of valour he had accomplished single-handed the day before, and feared to resume the fight. 'They remained afar off, and threw themselves down on the earth, to entreat the king in the sight [of his army]. And the king had power over them and slew them without their being able to escape. As bodies tumbled before his horses, so they lay there stretched out all together in their blood. Then the king of the hostile people of the Hittites sent a messenger to pray piteously to the great name of the king, speaking thus: "Thou art Ra-Hormakhis. Thy terror is upon the land of the Hittites, for thou hast broken the neck of the Hittites for ever and ever."' The army of Ramses seconded the prayer of the herald that the Egyptians and Hittites should henceforward be 'brothers together.' A treaty was accordingly made; but it was soon broken, and it was not until sixteen years later that peace was finally established between the two rival powers. The act of personal prowess upon which the heroic poem of Pentaur was built may have covered what had really been a check to the Egyptian arms. At all events, it is significant that no attempt was made to capture Kadesh, and that even the poet acknowledges how ready the Egyptian soldiers were to come to terms with their enemies. Equally significant is the fact that the war against the Hittites still went on; in the eighth year of the Pharaoh's reign Palestine was overrun and certain cities captured, including Dapur or Tabor 'in the land of the Amorites,' while other campaigns were directed against Ashkelon, in the south, and the city of Tunep or Tennib, in the north. When a lasting treaty of peace was at last concluded in the twenty-first year of Ramses, its conditions show that 'the great king of the Hittites' treated on equal terms with the great king of Egypt, and that even Ramses himself, whom later legend magnified into the Sesostris of the Greeks, was fain to acknowledge the power of his Hittite adversaries. The treaty was sealed by the marriage of the Pharaoh with the daughter of the Hittite king. The treaty, of which we possess the Egyptian text in full, was a very remarkable one, not only because it is the first treaty of the kind of which we know, but also on account of its contents. It ran as follows1:— 'In the year twenty-one, in the month Tybi, on the 21st day of the month, in the reign of King Ramessu Miamun, the dispenser of life eternally and for ever, the worshipper of the divinities Amon-Ra (of Thebes), Hormakhu (of Heliopolis), Ptah (of Memphis), Mut the lady of the Asher-lake (near Karnak), and Khonsu, the peace-loving, there took place a public sitting on the throne of Horus among the living, resembling his father Hormakhu in eternity, in eternity, evermore. 'On that day the king was in the city of Ramses, presenting his peace-offerings to his father Amon-Ra, and to the gods Hormakhu-Tum, to Ptah of Ramessu-Miamun, and to Sutekh, the strong, the son of the goddess of heaven Nut, that they might grant to him many thirty years' jubilee feasts, and innumerable happy years, and the subjection of all peoples under his feet for ever. 'Then came forward the ambassador of the king, and the Adon [of his house, by name ..., and presented the ambassadors] of the great king of Kheta, Kheta-sira, who were sent to Pharaoh to propose friendship with the king Ramessu Miamun, the dispenser of life eternally and for ever, just as his father the Sun-god [dispenses it] each day. 'This is the copy of the contents of the silver tablet, which the great king of Kheta, Kheta-sira, had caused to be made, and which was presented to the Pharaoh by the hand of his ambassador Tartisebu and his ambassador Ra-mes, to propose friendship with the king Ramessu Miamun, the bull among the princes, who places his boundary-marks where it pleases him in all lands. 'The treaty which had been proposed by the great king of Kheta, Kheta-sira, the powerful, the son of Maur-sira, the powerful, the son of the son of Sapalil, the great king of Kheta, the powerful, on the silver tablet, to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, the powerful, the son of Meneptah Seti, the great prince of Egypt, the powerful, the son's son of Ramessu I., the great king of Egypt, the powerful,—this was a good treaty for friendship and concord, which assured peace [and established concord] for a longer period than was previously the case, since a long time. For it was the agreement of the great prince of Egypt in common with the great king of Kheta, that the god should not allow enmity to exist between them, on the basis of a treaty. 'To wit, in the times of Mautal, the great king of Kheta, my brother, he was at war with [Meneptah Seti] the great prince of Egypt. 'But now, from this very day forward, Kheta-sira, the great king of Kheta, shall look upon this treaty, so that the agreement may remain, which the god Ra has made, which the god Sutekh has made, for the people of Egypt and for the people of Kheta, that there should be no more enmity between them for evermore.' And these are the contents:— 'Kheta-sira, the great king of Kheta, is in covenant with Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, from this very day forward, that there may subsist a good friendship and a good understanding between them for evermore. 'He shall be my ally; he shall be my friend: I will be his ally; I will be his friend: for ever. 'To wit, in the time of Mautal, the great king of Kheta, his brother, after his murder Kheta-sira placed himself on the throne of his father as the great king of Kheta. I strove for friendship with Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, and it is [my wish] that the friendship and the concord may be better than the friendship and the concord which before existed, and which was broken. 'I declare: I, the great king of Kheta, will hold together with [Ramessu Miamun], the great prince of Egypt, in good friendship and in good concord. The sons of the sons of the great king of Kheta will hold together and be friends with the sons of the sons of Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt. 'In virtue of our treaty for concord, and in virtue of our agreement [for friendship, let the people] of Egypt [be united in friendship] with the people of Kheta. Let a like friendship and a like concord subsist in such manner for ever. 'Never let enmity rise between them. Never let the great king of Kheta invade the land of Egypt, if anything shall have been plundered from it. Never let Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, over-step the boundary of the land [of Kheta, if anything shall have been plundered] from it. 'The just treaty, which existed in the times of Sapalil, the great king of Kheta, likewise the just treaty which existed in the times of Mautal, the great king of Kheta, my brother, that will I keep. 'Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, declares that he will keep it. [We have come to an understanding about it] with one another at the same time from this day forward, and we will fulfil it, and will act in a righteous manner. 'If another shall come as an enemy to the lands of Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, then let him send an embassy to the great king of Kheta to this effect: "Come! and make me stronger than him." Then shall the great king of Kheta [assemble his warriors], and the king of Kheta [shall come] to smite his enemies. But if it should not be the wish of the great king of Kheta to march out in person, then he shall send his warriors and his chariots, that they may smite his enemies. Otherwise [he would incur] the wrath of Ramessu Miamun, [the great prince of Egypt. And if Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, should banish] for a crime subjects from his country, and they should commit another crime against him, then shall he (the king of Kheta) come forward to kill them. The great king of Kheta shall act in common with [the great prince of Egypt. 'If another should come as an enemy to the lands of the great king of Kheta, then shall he send an embassy to the great prince of Egypt with the request that] he would come in great power to kill his enemies; and if it be the intention of Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, to come (himself), he shall [smite the enemies of the great king of Kheta. If it is not the intention of the great prince of Egypt to march out in person, then he shall send his warriors and his two-] horse chariots, while he sends back the answer to the people of Kheta. 'If any subjects of the great king of Kheta have offended him, then Ramessu Miamun, [the great prince of Egypt, shall not receive them in his land, but shall advance to kill them] ... the oath, with the wish to say: I will go ... until ... Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, living for ever ... that he may be given for them (?) to the lord, and that Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, may speak according to his agreement evermore.... '[If servants shall flee away] out of the territories of Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, to betake themselves to the great king of Kheta, the great king of Kheta shall not receive them, but the great king of Kheta shall give them up to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, [that they may receive their punishment. 'If servants of Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, leave his country], and betake themselves to the land of Kheta, to make themselves servants of another, they shall not remain in the land of Kheta; [they shall be given up] to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt. 'If, on the other hand, there should flee away [servants of the great king of Kheta, in order to betake themselves to] Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, [in order to stay in Egypt], then those who have come from the land of Kheta in order to betake themselves to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, shall not be [received by] Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, [but] the great prince of Egypt, Ramessu Miamun, [shall deliver them up to the great king of Kheta]. '[And if there shall leave the land of Kheta persons] of skilful mind, so that they come to the land of Egypt to make themselves servants of another, then Ramessu Miamun will not allow them to settle, he will deliver them up to the great king of Kheta. 'When this [treaty] shall be known [by the inhabitants of the land of Egypt and of the land of Kheta, then shall they not offend against it, for all that stands written on] the silver tablet, these are words which will have been approved by the company of the gods among the male gods and among the female gods, among those namely of the land of Egypt. They are witnesses for me [to the validity] of these words, [which they have allowed. 'This is the catalogue of the gods of the land of Kheta:—

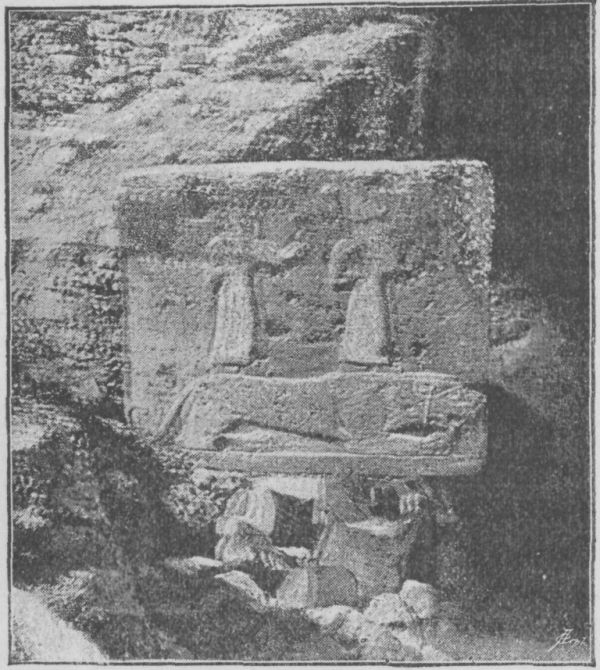

'[I have invoked these male and these] female [gods of the land of Kheta, these are the gods] of the land, [as witnesses to] my oath. [With them have been associated the male and the female gods] of the mountains and of the rivers of the land of Kheta, the gods of the land of Qazauadana, Amon, Ra, Sutekh, and the male and female gods of the land of Egypt, of the earth, of the sea, of the winds, and of the storms. 'With regard to the commandment which the silver tablet contains for the people of Kheta and for the people of Egypt, he who shall not observe it shall be given over [to the vengeance] of the company of the gods of Kheta, and shall be given over [to the vengeance] of the gods of Egypt, [he] and his house and his servants. 'But he who shall observe these commandments which the silver tablet contains, whether he be of the people of Kheta or [of the people of Egypt], because he has not neglected them, the company of the gods of the land of Kheta and the company of the gods of the land of Egypt shall secure his reward and preserve life [for him] and his servants and those who are with him and who are with his servants. 'If there flee away of the inhabitants [one from the land of Egypt], or two or three, and they betake themselves to the great king of Kheta [the great king of Kheta shall not] allow them [to remain, but he shall] deliver them up, and send them back to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt. 'Now with respect to the [inhabitant of the land of Egypt], who is delivered up to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, his fault shall not be avenged upon him, his [house] shall not be taken away, nor his [wife] nor his [children]. There shall not be [put to death his mother, neither shall he be punished in his eyes, nor on his mouth, nor on the soles of his feet], so that thus no crime shall be brought forward against him. 'In the same way shall it be done if inhabitants of the land of Kheta take to flight, be it one alone, or two, or three, to betake themselves to Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt. Ramessu Miamun, the great prince of Egypt, shall cause them to be seized, and they shall be delivered up to the great king of Kheta. '[With regard to] him who [is delivered up, his crime shall not be brought forward against him]. His [house] shall not be taken away, nor his wives, nor his children, nor his people; his mother shall not be put to death; he shall not be punished in his eyes, nor on his mouth, nor on the soles of his feet, nor shall any accusation be brought forward against him. 'That which is in the middle of this silver tablet and on its front side is a likeness of the god Sutekh ..., surrounded by an inscription to this effect: "This is the [picture] of the god Sutekh, the king of heaven and [earth]." At the time (?) of the treaty which Kheta-sira, the great king of the Kheta, made....' This compact of offensive and defensive alliance proves more forcibly than any description the position to which the Hittite empire had attained. It ranked side by side with the Egypt of Ramses, the last great Pharaoh who ever ruled over the land of the Nile. With Egypt it had contested the sovereignty of Western Asia, and had compelled the Egyptian monarch to consent to peace. Egypt and the Hittites were now the two leading powers of the world. The treaty was ratified by the visit of the Hittite prince Kheta-sira to Egypt in his national costume, and the marriage of his daughter to Ramses in the thirty-fourth year of the Pharaoh's reign (B. C. 1354). She took the Egyptian name of Ur-maa Noferu-Ra, and her beauty was celebrated by the scribes of the court. Syria was handed over to the Hittites as their legitimate possession; Egypt never again attempted to wrest it from them, and if the Hittite yoke was to be shaken off it must be through the efforts of the Syrians themselves. For a while, however, 'the great king of the Hittites' preserved his power intact; his supremacy was acknowledged from the Euphrates in the east to the ∆gean Sea in the west, from Kappadokia in the north to the tribes of Canaan in the south. Even Naharina, once the antagonist of the Egyptian Pharaohs, acknowledged his sovereignty, and Pethor, the home of Balaam, at the junction of the Euphrates and the Sajur, became a Hittite town. The cities of Philistia, indeed, still sent tribute to the Egyptian ruler, but northwards the Hittite sway seems to have been omnipotent. The Amorites of the mountains allied themselves with 'the children of Heth,' and the Canaanites in the lowlands looked to them for protection. The Israelites had not as yet thrust themselves between the two great powers of the Oriental world: it was still possible for a Hittite sovereign to visit Egypt, and for an Egyptian traveller to explore the cities of Canaan. After sixty-six years of vainglorious splendour the long reign of Ramses II. came to an end (B.C. 1322). The Israelites had toiled for him in building Pithom and Raamses, and on the accession of his son and successor, Meneptah, they demanded permission to depart from Egypt. The history of the Exodus is too well known to be recounted here; it marks the close of the period of conquest and prosperity which Egypt had enjoyed under the kings of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties. Early in his reign Meneptah had sent corn by sea to the Hittites at a time when there was a famine in Syria, showing that the peaceful relations established during the reign of his father were still in force. Despatches dated in his third year also exist, which speak of letters and messengers passing to and fro between Egypt and Phœnicia, and make it clear that Gaza was still garrisoned by Egyptian troops. But in the fifth year of his reign Egypt was invaded by a confederacy of white-skinned tribes from Libya and the shores of Asia Minor, who overran the Delta and threatened the very existence of the Egyptian monarchy. Egypt, however, was saved by a battle in which the invading host was almost annihilated, but not before it had itself been half drained of its resources, and weakened correspondingly. Not many years afterwards the dynasty of Ramses the Oppressor descended to its grave in bloodshed and disaster. Civil war broke out, followed by foreign invasion, and the crown was seized by 'Arisu the Phœnician.' But happier times again arrived. Once more the Egyptians obeyed a native prince, and the Twentieth Dynasty was founded. Its one great king was Ramses III., who rescued his country from two invasions more formidable even than that which had been beaten back by Meneptah. Like the latter, they were conducted by the Libyans and the nations of the Greek seas, and the invaders were defeated partly on the land, partly on the water. The maritime confederacy included the Teukrians of the Troad, the Lykians and the Philistines, perhaps also the natives of Sardinia and Sicily. They had flung themselves in the first instance on the coasts of Phœnicia, and spread inland as far as Carchemish. Laden with spoil, they fixed their camp 'in the land of the Amorites,' and then descended upon Egypt. The Hittites of Carchemish and the people of Matenau of Naharina came in their train, and a long and terrible battle took place on the sea-shore between Raphia and Pelusium. The Egyptians were victorious; the ships of the enemy were sunk, and their soldiers slain or captured. Egypt was once more filled with captives, and the flame of its former glory flickered again for a moment before finally going out. The list of prisoners shows that the Hittite tribes had taken part in the struggle, Carchemish, Aleppo, and Pethor being specially named as having sent contingents to the war. They had probably marched by land, while their allies from Asia Minor and the islands of the Mediterranean had attacked the Egyptian coast in ships. So far as we can gather, the Hittite populations no longer acknowledged the suzerainty of an imperial sovereign, but were divided into independent states. It would seem, too, that they had lost their hold upon Mysia and the far west. The Tsekkri and the Leku, the Shardaina and the Shakalsha are said to have attacked their cities before proceeding on their southward march. If we can trust the statement, we must conclude that the Hittite empire had already broken up. The tribes of Asia Minor it had conquered were in revolt, and had carried the war into the homes of their former masters. However this may be, it is certain that from this time forward the power of the Hittites in Syria began to wane. Little by little the Aramśan population pushed them back into their northern fastnesses, and throughout the period of the Israelitish judges we never hear even of their name. The Hittite chieftains advance no longer to the south of Kadesh; and though Israel was once oppressed by a king who had come from the north, he was king of Aram-Naharaim, the Naharina of the Egyptian texts, and not a Hittite prince. Where the Egyptian monuments desert us, those of Assyria come to our help. The earliest notices of the Hittites found in the cuneiform texts are contained in a great work on astronomy and astrology, originally compiled for an early king of Babylonia. The references to 'the king of the Hittites,' however, which meet us in it, cannot be ascribed to a remote date. One of the chief objects aimed at by the author (or authors) of the work was to foretell the future, it being supposed that a particular event which had followed a certain celestial phenomenon would be repeated when the phenomenon happened again. Consequently it was the fashion to introduce into the work from time to time fresh notices of events; and some of these glosses, as we may term them, are probably not older than the seventh century B.C. It is, therefore, impossible to determine the exact date to which the allusions to the Hittite king belong, but there are indications that it is comparatively late. The first clear account that the Assyrian inscriptions give us concerning the Hittites, to which we can attach a date, is met with in the annals of Tiglath-pileser I. Tiglath-pileser I. was the most famous monarch of the first Assyrian empire, and he reigned about 1110 B.C. He carried his arms northward and westward, penetrating into the bleak and trackless mountains of Armenia, and forcing his way as far as Malatiyeh in Kappadokia. His annals present us with a very full and interesting picture of the geography of these regions at the time of his reign. Kummukh or KomagÍnÍ, which at that epoch extended southward from Malatiyeh in the direction of Carchemish, was one of the first objects of his attack. 'At the beginning of my reign,' he says, '20,000 Moschians (or men of Meshech) and their five kings, who for fifty years had taken possession of the countries of Alzi and Purukuzzi, which had formerly paid tribute and taxes to Assur my lord—no king (before me) had opposed them in battle—trusted to their strength, and came down and seized the land of Kummukh.' The Assyrian king, however, marched against them, and defeated them in a pitched battle with great slaughter, and then proceeded to carry fire and sword through the cities of Kummukh. Its ruler Kili-anteru, the son of Kali-anteru, was captured along with his wives and family; and Tiglath-pileser next proceeded to besiege the stronghold of Urrakhinas. Its prince Sadi-anteru, the son of Khattukhi, 'the Hittite,' threw himself at the conqueror's feet; his life was spared, and 'the wide-spreading land of Kummukh' became tributary to Assyria, objects of bronze being the chief articles it had to offer. About the same time, 4000 troops belonging to the Kask‚ or Kolkhians and the people of Uruma, both of whom are described as 'soldiers of the Hittites' and as having occupied the northern cities of Mesopotamia, submitted voluntarily to the Assyrian monarch, and were transported to Assyria along with their chariots and their property. Uruma was the Urima of classical geography, which lay on the Euphrates a little to the north of Birejik, so that we know the exact locality to which these 'Hittite soldiers' belonged. In fact, 'Hittite' must have been a general name given to the inhabitants of all this district; the modern Merash, for instance, lies within the limits of the ancient Kummukh; and, as we shall see, it is from Merash that a long Hittite inscription has come. Tiglath-pileser attacked Kummukh a second time, and on this occasion penetrated still further into the mountain fastnesses of the Hittite country. In a third campaign his armies came in sight of Malatiyeh itself, but the king contented himself with exacting a small yearly tribute from the city, 'having had pity upon it,' as he tells us, though more probably the truth was that he found himself unable to take it by storm. But he never succeeded in forcing his way across the fords of the Euphrates, which were commanded by the great fortress of Carchemish. Once he harried the land of Mitanni or Naharina, slaying and spoiling 'in one day' from Carchemish southwards to a point that faced the deserts of the nomad Sukhi, the Shuhites of the Book of Job. It was on this occasion that he killed ten elephants in the neighbourhood of Harran and on the banks of the Khabour, besides four wild bulls which he hunted with arrows and spears 'in the land of Mitanni and in the city of Araziqi4, which lies opposite to the land of the Hittites.' Towards the end of the twelfth century before our era, therefore, the Hittites were still strong enough to keep one of the mightiest of the Assyrian kings in check. It is true that they no longer obeyed a single head; it is also true that that portion of them which was settled in the land of Kummukh was overrun by the Assyrian armies, and forced to pay tribute to the Assyrian invader. But Carchemish compelled the respect of Tiglath-pileser; he never ventured to approach its walls or to cross the river which it was intended to defend. His way was barred to the west, and he never succeeded in traversing the high road which led to Phœnicia and Palestine. After the death of Tiglath-pileser I. the Assyrian inscriptions fail us. His successors allowed the empire to fall into decay, and more than two hundred years elapsed before the curtain is lifted again. These two hundred years had witnessed the rise and fall of the kingdom of David and Solomon as well as the growth of a new power, that of the Syrians of Damascus. Damascus rose on the ruins of the empire of Solomon. But its rise also shows plainly that the power of the Hittites in Syria was beginning to wane. Hadad-ezer, king of Zobah, the antagonist of David, had been able to send for aid to the Arameans of Naharina, on the eastern side of the Euphrates (2 Sam. x. 16), and with them he had marched to Helam, in which it is possible to see the name of Aleppo5. It is clear that the Hittites were no longer able to keep the Aramean population in subjection, or to prevent an Aramean prince of Zobah from expelling them from the territory they had once made their own. Indeed, it may be that in one passage of the Old Testament allusion is made to an attack which Hadad-ezer was preparing against them. When it is stated that he was overthrown by David, 'as he was going to turn his hand against the river Euphrates' (2 Sam. viii. 3), it may be that it was against the Hittites of Carchemish that his armies were about to be directed. At any rate, support for this view is found in a further statement of the sacred historian. 'When Toi king of Hamath,' we learn, 'heard that David had smitten all the host of Hadad-ezer, then Toi sent Joram his son unto king David, to salute him, and to bless him, because he had fought against Hadad-ezer and smitten him; for Hadad-ezer had wars with Toi' (2 Sam. viii. 9, 10). Now we know from the monuments that have been discovered on the spot that Hamath was once a Hittite city, and there is no reason for not believing that it was still in the possession of the Hittites in the age of David. Its Syrian enemies would in that case have been the same as the enemies of David, and a common danger would thus have united it with Israel in an alliance which ended only in its overthrow by the Assyrians. As late as the time of Uzziah, we are told by the Assyrian inscriptions, the Jewish king was in league with Hamath, and the last independent ruler of Hamath was Yahu-bihdi, a name in which we recognise that of the God of Israel. Indeed, the very fact that the Syrians imagined that 'the kings of the Hittites' were coming to the rescue of Samaria, when besieged by the forces of Damascus, goes to show that Israel and the Hittites were regarded as natural friends, whose natural adversaries were the Arameans of Syria. As the power and growth of Israel had been built up on the conquest and subjugation of the Semitic populations of Palestine, so too the power of the Hittites had been gained at the expense of their Semitic neighbours. The triumph of Syria was a blow alike to the Hittites of Carchemish and to the Hebrews of Samaria and Jerusalem. With Assur-natsir-pal, whose reign extended from B.C. 885 to 860, contemporaneous Assyrian history begins afresh. His campaigns and conquests rivalled those of Tiglath-pileser I., and indeed exceeded them both in extent and in brutality. Like his predecessor, he exacted tribute from Kummukh as well as from the kings of the country in which Malatiyeh was situated; but with better fortune than Tiglath-pileser he succeeded in passing the Euphrates, and obliging Sangara of Carchemish to pay him homage. It is clear that Carchemish was no longer as strong as it had been two centuries before, and that the power of its defenders was gradually vanishing away. There was still, however, a small Hittite population on the eastern bank of the Euphrates; at all events, Assur-natsir-pal describes the tribe of Bakhian on that side of the river as Hittite, and it was only after receiving tribute from them that he crossed the stream in boats and approached the land of Gargamis or Carchemish. But his threatened assault upon the Hittite stronghold was bought off with rich and numerous presents. Twenty talents of silver—the favourite metal of the Hittite princes—'cups of gold, chains of gold, blades of gold, 100 talents of copper, 250 talents of iron, gods of copper in the form of wild bulls, bowls of copper, libation cups of copper, a ring of copper, the multitudinous furniture of the royal palace, of which the like was never received, couches and thrones of rare woods and ivory, 200 slave-girls, garments of variegated cloth and linen, masses of black crystal and blue crystal, precious stones, the tusks of elephants, a white chariot, small images of gold,' as well as ordinary chariots and war-horses,—such were the treasures poured into the lap of the Assyrian monarch by the wealthy but unwarlike king of Carchemish. They give us an idea of the wealth to which the city had attained through its favourable position on the high-road of commerce that ran from the east to the west. The uninterrupted prosperity of several centuries had filled it with merchants and riches; in later days we find the Assyrian inscriptions speaking of 'the maneh of Carchemish' as one of the recognised standards of value. Carchemish had become a city of merchants, and no longer felt itself able to oppose by arms the trained warriors of the Assyrian king. Quitting Carchemish, Assur-natsir-pal pursued his march westwards, and after passing the land of Akhanu on his left, fell upon the town of Azaz near Aleppo, which belonged to the king of the Patinians. The latter people were of Hittite descent, and occupied the country between the river Afrin and the shores of the Gulf of Antioch. The Assyrian armies crossed the Afrin and appeared before the walls of the Patinian capital. Large bribes, however, induced them to turn away southward, and to advance along the Orontes in the direction of the Lebanon. Here Assur-natsir-pal received the tribute of the Phœnician cities. Shalmaneser II., the son and successor of Assur-natsir-pal, continued the warlike policy of his father (B.C. 860-825). The Hittite princes were again a special object of attack. Year after year Shalmaneser led his armies against them, and year after year did he return home laden with spoil. The aim of his policy is not difficult to discover. He sought to break the power of the Hittite race in Syria, to possess himself of the fords across the Euphrates and the high-road which brought the merchandise of Phœnicia to the traders of Nineveh, and eventually to divert the commerce of the Mediterranean to his own country. By the overthrow of the Patinians he made himself master of the cedar forests of Amanus, and his palaces were erected with the help of their wood. Sangara of Carchemish, it is true, perceived his danger, and a league of the Hittite princes was formed to resist the common foe. Contingents came not only from Kummukh and from the Patinians, but from Cilicia and the mountain ranges of Asia Minor. It was, however, of no avail. The Hittite forces were driven from the field, and their leaders were compelled to purchase peace by the payment of tribute. Once more Carchemish gave up its gold and silver, its bronze and copper, its purple vestures and curiously-adorned thrones, and the daughter of Sangara himself was carried away to the harem of the Assyrian king. Pethor, the city of Balaam, was turned into an Assyrian colony, its very name being changed to an Assyrian one. The way into Hamath and Phœnicia at last lay open to the Assyrian host. At Aleppo Shalmaneser offered sacrifices to the native god Hadad, and then descended upon the cities of Hamath. At Karkar he was met by a great confederacy formed by the kings of Hamath and Damascus, to which Ahab of Israel had contributed 2000 chariots and 10,000 men. But nothing could withstand the onslaught of the Assyrian veterans. The enemy were scattered like chaff, and the river Orontes was reddened with their blood. The battle of Karkar (in B.C. 854) brought the Assyrians into contact with Damascus, and caused Jehu on a later occasion to send tribute to the Assyrian king. The subsequent history of Shalmaneser concerns us but little. The power of the Hittites south of the Taurus had been broken for ever. The Semite had avenged himself for the conquest of his country by the northern mountaineers centuries before. They no longer formed a barrier which cut off the east from the west, and prevented the Semites of Assyria and Babylon from meeting the Semites of Phœnicia and Palestine. The intercourse which had been interrupted in the age of the nineteenth dynasty of Egypt could now be again resumed. Carchemish ceased to command the fords of the Euphrates, and was forced to acknowledge the supremacy of the Assyrian invader. In fact, the Hittites of Syria had become little more than tributaries of the Assyrian monarch. When an insurrection broke out among the Patinians, in consequence of which the rightful king was killed and his throne seized by an usurper, Shalmaneser claimed and exercised the right to interfere. A new sovereign was appointed by him, and he set up an image of himself in the capital city of the Patinian people. The change that had come over the relations between the Assyrians and the Hittite population is marked by a curious fact. From the time of Shalmaneser onwards, the name of Hittite is no longer used by the Assyrian writers in a correct sense. It is extended so as to embrace all the inhabitants of Northern Syria on the western side of the Euphrates, and subsequently came to include the inhabitants of Palestine as well. Khatta or 'Hittite' became synonymous with Syrian. How this happened is not difficult to explain. The first populations of Syria with whom the Assyrians had come into contact were of Hittite origin. When their power was broken, and the Assyrian armies had forced their way past the barrier they had so long presented to the invader, it was natural that the states next traversed by the Assyrian generals should be supposed also to belong to them. Moreover, many of these states were actually dependent on the Hittite princes, though inhabited by an Aramean people. The Hittites had imposed their yoke upon an alien race of Aramean descent, and accordingly in Northern Syria Hittite and Aramean cities and tribes were intermingled together. 'I took,' says Shalmaneser, 'what the men of the land of the Hittites had called the city of Pethor (Pitru), which is upon the river Sajur (Sagura), on the further side of the Euphrates, and the city of MudkÓnu, on the eastern side of the Euphrates, which Tiglath-pileser (I.), the royal forefather who went before me, had united to my country, and Assur-rab-buri king of Assyria and the king of the Arameans had taken (from it) by a treaty.' At a later date Shalmaneser marched from Pethor to Aleppo, and there offered sacrifices to 'the god of the city,' Hadad-Rimmon, whose name betrays the Semitic character of its population. The Hittites, in short, had never been more than a conquering upper class in Syria, like the Normans in Sicily; and as time went on the subject population gained more and more upon them. Like all similar aristocracies, they tended to die out or to be absorbed into the native population of the country. They still held possession of Carchemish, however, and the decadence of the first Assyrian empire gave them an unexpected respite. But the revolution which placed Tiglath-pileser III. on the throne of Assyria, in B.C. 725, brought with it the final doom of Hittite supremacy. Assyria entered upon a new career of conquest, and under its new rulers established an empire which extended over the whole of Western Asia. In B.C. 717 Carchemish finally fell before the armies of Sargon, and its last king Pisiris became the captive of the Assyrian king. Its trade and wealth passed into Assyrian hands, it was colonised by Assyrians and placed under an Assyrian satrap. The great Hittite stronghold on the Euphrates, which had been for so many centuries the visible sign of their power and southern conquests, became once more the possession of a Semitic people. The long struggle that had been carried on between the Hittites and the Semites was at an end; the Semite had triumphed, and the Hittite was driven back into the mountains from whence he had come. But he did not yield without a struggle. The year following the capture of Carchemish saw Sargon confronted by a great league of the northern peoples, Meshech, Tubal, Melitene and others, under the leadership of the king of Ararat. The league, however, was shattered in a decisive battle, the king of Ararat committed suicide, and in less than three years KomagÍnÍ was annexed to the Assyrian empire. The Semite of Nineveh was supreme in the Eastern world. Ararat was the name given by the Assyrians to the district in the immediate neighbourhood of Lake Van, as well as to the country to the south of it. It was not until post-Biblical days that the name was extended to the north, so that the modern Mount Ararat obtained a title which originally belonged to the Kurdish range in the south. But Ararat was not the native name of the country. This was Biainas or Bianas, a name which still survives in that of Lake Van. Numerous inscriptions are scattered over the country, written in cuneiform characters borrowed from Nineveh in the time of Assur-natsir-pal or his son Shalmaneser, but in a language which bears no resemblance to that of Assyria. They record the building of temples and palaces, the offerings made to the gods, and the campaigns of the Vannic kings. Among the latter mention is made of campaigns against the Kh‚te or Hittites. The first of these campaigns was conducted by a king called Menuas, who reigned in the ninth century before our era. He overran the land of Alzi, and then found himself in the land of the Hittites. Here he plundered the cities of Surisilis and Tarkhi-gamas, belonging to the Hittite prince Sada-halis, and captured a number of soldiers, whom he dedicated to the service of his god Khaldis. On another occasion he marched as far as the city of Malatiyeh, and after passing through the country of the Hittites, caused an inscription commemorating his conquests to be engraved on the cliffs of Palu. Palu is situated on the northern bank of the Euphrates, about midway between Malatiyeh and Van, and as it lies to the east of the ancient district of Alzi, we can form some idea of the exact geographical position to which the Hittites of Menuas must be assigned. His son and successor, Argistis I, again made war upon them, and we gather from one of his inscriptions that the city of Malatiyeh was itself included among their fortresses. The 'land of the Hittites,' according to the statements of the Vannic kings, stretched along the banks of the Euphrates from Palu on the east as far as Malatiyeh on the west. The Hittites of the Assyrian monuments lived to the south-west of this region, spreading through KomagÍnÍ to Carchemish and Aleppo. The Egyptian records bring them yet further south to Kadesh on the Orontes, while the Old Testament carries the name into the extreme south of Palestine. It is evident, therefore, that we must see in the Hittite tribes fragments of a race whose original seat was in the ranges of the Taurus, but who had pushed their way into the warm plains and valleys of Syria and Palestine. They belonged originally to Asia Minor, not to Syria, and it was conquest only which gave them a right to the name of Syrians. 'Hittite' was their true title, and whether the tribes to which it belonged lived in Judah or on the Orontes, at Carchemish or in the neighbourhood of Palu, this was the title under which they were known. We must regard it as a national name, which clung to them in all their conquests and migrations, and marked them out as a peculiar people, distinct from the other races of the Eastern world. It is now time to see what their own monuments have to tell us regarding them, and the influence they exercised upon the history of mankind. SLAB FOUND AT MERASH.

|

|

|

|

|

1) This translation is the one given by Brugsch in the second edition of the English translation of his History of Egypt. 2) Now Tennib in Northern Syria. 3) Also read Antarata. 4) Called Eragiza in classical geography and in the Talmud. 5) Called Khalman in the Assyrian texts. Josephus changes Helam into the proper name Khalaman.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD