By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 12 - The Hittites: The Story of a Forgotten Empire

A. H. Sayce, LL.D.

Chapter 3

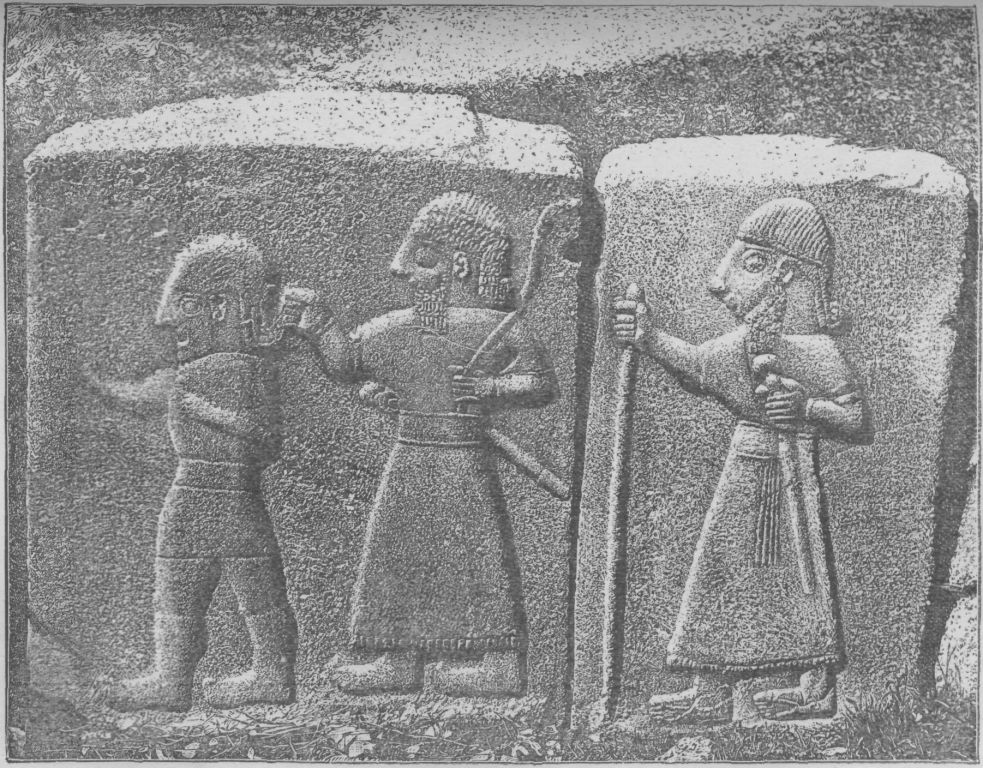

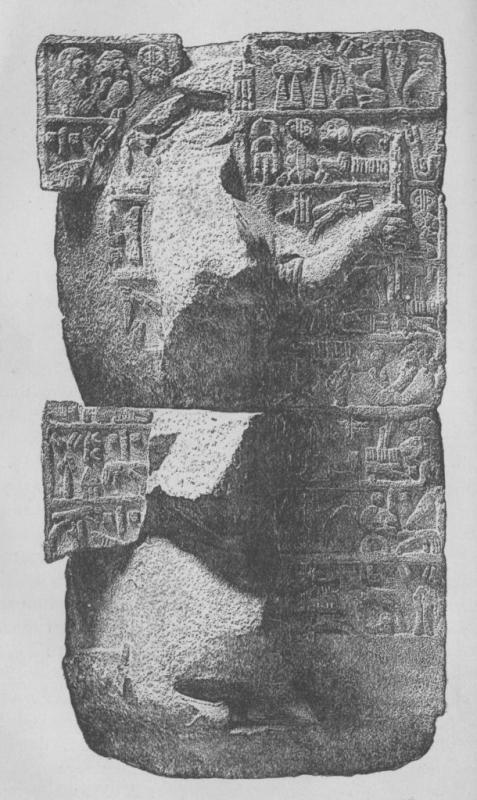

THE HITTITE MONUMENTS.It was a warm and sunny September morning when I left the little town of Nymphi near Smyrna with a strong escort of Turkish soldiers, and made my way to the Pass of Karabel. The Pass of Karabel is a narrow defile, shut in on either side by lofty cliffs, through which ran the ancient road from Ephesos in the south to Sardes and Smyrna in the north. The Greek historian Herodotos tells us that the Egyptian conqueror Sesostris had left memorials of himself in this place. 'Two images cut by him in the rock' were to be seen beside the roads which led 'from Ephesos to Phokaea and from Sardes to Smyrna. On either side a man is carved, a little over three feet in height, who holds a spear in the right hand and a bow in the left. The rest of his accoutrement is similar, for it is Egyptian and Ethiopian, and from one shoulder to the other, right across the breast, Egyptian hieroglyphics have been cut which declare: "I have won this land with my shoulders."' These two images were the object of my journey. One of them had been discovered by Renouard in 1839, and shortly afterwards sketched by Texier; the other had been found by Dr. Beddoe in 1856. But visitors to the Pass in which they were engraved were few and far between; the cliffs on either side were the favourite haunt of brigands, and thirty soldiers were not deemed too many to protect my safety. My work of exploration had to be carried on under the shelter of their guns, for more than twenty bandits were lurking under the brushwood above. The sculpture sketched by Texier had subsequently been photographed by Mr. Svoboda. It represents a warrior whose height is rather more than life-size, and who stands in profile with the right foot planted in front of him, in the attitude of one who is marching. In his right hand he holds a spear, behind his left shoulder is slung a bow, and the head is crowned with a high peaked cap. He is clad in a tunic which reaches to the knees, and his feet are shod with boots with turned-up ends. The whole figure is cut in deep relief in an artificial niche, and between the spear and the face are three lines of hieroglyphic characters. The figure faces south, and is carved on the face of the eastern cliff of Karabel. It had long been recognised that the hieroglyphics were not those of Egypt, and Professor Perrot had also drawn attention to the striking resemblance between the style of art represented by this sculpture and that represented by certain rock-sculptures in Kappadokia, as well as by the sculptured image of a warrior discovered by himself at a place called Ghiaur-kalessi, 'the castle of the infidel,' in Phrygia, which is practically identical in form and character with the sculptured warrior of Karabel. What was the origin of this art, or who were the people it commemorated, was a matter of uncertainty. A few weeks, however, before my visit to the Pass of Karabel, I announced6 that I had come to the conclusion that the art was Hittite, and that the hieroglyphics accompanying the figure at Karabel would turn out, when carefully examined, to be Hittite also. The primary purpose of my visit to the pass was to verify this conclusion. Let us now see how I had arrived at it. The story is a long one, and in order to understand it, it is necessary to transport ourselves from the Pass of Karabel in Western Asia Minor to Hamah, the site of the ancient Hamath, in the far east. It was here that the first discovery was made which has led by slow degrees to the reconstruction of the Hittite empire, and a recognition of the important part once played by the Hittites in the history of the civilised world. As far back as the beginning of the present century (in 1812) the great Oriental traveller Burckhardt had noticed a block of black basalt covered with strange-looking hieroglyphics built into the corner of a house in one of the bazaars of Hamah7. But the discovery was forgotten, and the European residents in Hamah, like the travellers who visited the city, were convinced that 'no antiquities' were to be found there. Nearly sixty years later, however, when the American Palestine Exploration Society was first beginning its work, the American consul, Mr. Johnson, and an American missionary, Mr. Jessup, accidentally lighted again upon this stone, and further learned that three other stones of similar character, and inscribed with similar hieroglyphics, existed elsewhere in Hamah. One of them, of very great length, was believed to be endowed with healing properties. Rheumatic patients, Mohammedans and Christians alike, were in the habit of stretching themselves upon it, in the firm belief that their pains would be absorbed into the stone. The other inscribed stones were also regarded with veneration, which naturally increased when it was known that they were being sought after by the Franks; and the two Americans found it impossible to see them all, much less to take copies of the inscriptions they bore. They had to be content with the miserable attempts at reproducing them made by a native painter, one of which was afterwards published in America. The publication served to awaken the interest of scholars in the newly discovered inscriptions, and efforts were made by Sir Richard Burton and others to obtain correct impressions of them. All was in vain, however, and it is probable that the fanaticism or greed of the people of Hamah would have successfully resisted all attempts to procure trustworthy copies of the texts, had not a lucky accident brought Dr. William Wright to the spot. It is to his energy and devotion that the preservation of these precious relics of Hittite literature may be said to be due. 'On the 10th of November, 1872,' he tells us, he 'set out from Damascus, intent on securing the Hamah inscriptions. The Sublime Porte, seized by a periodic fit of reforming zeal, had appointed an honest man, Subhi Pasha, to be governor of Syria. Subhi Pasha brought a conscience to his work, and, not content with redressing wrongs that succeeded in forcing their way into his presence, resolved to visit every district of his province, in order that he might check the spoiler and discover the wants of the people. He invited me to accompany him on a tour to Hamah, and I gladly accepted the invitation.' Along with Mr. Green, the English Consul, accordingly, Dr. Wright joined the party of the Pasha; and, fearing that the same fate might befall the Hamath stones as had befallen the Moabite Stone, which had been broken into pieces to save it from the Europeans, persuaded him to buy them, and send them as a present to the Museum at Constantinople. When the news became known in Hamah, there were murmurings long and deep against the Pasha, and it became necessary, not only to appeal to the cupidity and fear of the owners of the stones, but also to place them under the protection of a guard of soldiers the night before the work of removing them was to commence. The night was an anxious one to Dr. Wright; but when day dawned, the stones were still safe, and the labour of their removal was at once begun. It 'was effected by an army of shouting men, who kept the city in an uproar during the whole day. Two of them had to be taken out of the walls of inhabited houses, and one of them was so large that it took fifty men and four oxen a whole day to drag it a mile. The other stones were split in two, and the inscribed parts were carried on the backs of camels to the' court of the governor's palace. Here they could be cleaned and copied at leisure and in safety. But the work of cleaning them from the accumulated dirt of ages occupied the greater part of two days. Then came the task of making casts of the inscriptions, with the help of gypsum which some natives had been bribed to bring from the neighbourhood. At length, however, the work was completed, and Dr. Wright had the satisfaction of sending home to England two sets of casts of these ancient and mysterious texts, one for the British Museum, the other for the Palestine Exploration Fund, while the originals themselves were safely deposited in the Museum of Constantinople. It was now time to inquire what the inscriptions meant, and who could have been the authors of them. Dr. Wright at once suggested that they were the work of the Hittites, and that they were memorials of Hittite writing. But his suggestion was buried in the pages of a periodical better known to theologians than to Orientalists, and the world agreed to call the writing by the name of Hamathite. It specially attracted the notice of Dr. Hayes Ward of New York, who discovered that the inscriptions were written in boustrophedon fashion, that is to say, that the lines turned alternately from right to left and from left to right, like oxen when plowing a field, the first line beginning on the right and the line following on the left. The lines read, in fact, from the direction towards which the characters look. Dr. Hayes Ward also made another discovery. In the ruins of the great palace of Nineveh Sir A. H. Layard had discovered numerous clay impressions of seals once attached to documents of papyrus or parchment. The papyrus and parchment have long since perished, but the seals remain, with the holes through which the strings passed that attached them to the original deeds. Some of the seals are Assyrian, some Phœnician, others again are Egyptian, but there are a few which have upon them strange characters such as had never been met with before. It was these characters which Dr. Hayes Ward perceived to be the same as those found upon the stones of Hamah, and it was accordingly supposed that the seals were of Hamathite origin. In 1876, two years after the publication of Dr. Wright's article, of which I had never heard at the time, I read a Paper on the Hamathite inscriptions before the Society of Biblical Archæology. In this I put forward a number of conjectures, one of them being that the Hamathite hieroglyphs were the source of the curious syllabary used for several centuries in the island of Cyprus, and another that the hieroglyphs were not an invention of the early inhabitants of Hamath, but represented the system of writing employed by the Hittites. We know from the Egyptian records that the Hittites could write, and that a class of scribes existed among them, and, since Hamath lay close to the borders of the Hittite kingdoms, it seemed reasonable to suppose that the unknown form of script discovered on its site was Hittite rather than Hamathite. The conjecture was confirmed almost immediately afterwards by the discovery of the site of Carchemish, the great Hittite capital, and of inscriptions there in the same system of writing as that found on the stones of Hamah. It was not long, therefore, before the learned world began to recognise that the newly-discovered script was the peculiar possession of the Hittite race. Dr. Hayes Ward was one of the first to do so, and the Trustees of the British Museum determined to institute excavations among the ruins of Carchemish. Meanwhile notice was drawn to a fact which showed that the Hittite characters, as we shall now call them, were employed, not only at Hamath and Carchemish, but in Asia Minor as well. More than a century ago a German traveller had observed two figures carved on a wall of rock near Ibreez, or Ivris, in the territory of the ancient Lykaonia. One of them was a god, who carried in his hand a stalk of corn and a bunch of grapes, the other was a man, who stood before the god in an attitude of adoration. Both figures were shod with boots with upturned ends, and the deity wore a tunic that reached to his knees, while on his head was a peaked cap ornamented with horn-like ribbons. A century elapsed before the sculpture was again visited by an European traveller, and it was again a German who found his way to the spot. On this occasion a drawing was made of the figures, which was published by Ritter in his great work on the geography of the world. But the drawing was poor and imperfect, and the first attempt to do adequate justice to the original was made by the Rev. E. J. Davis in 1875. He published his copy, and an account of the monument, in the Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archæology the following year. He had noticed that the figures were accompanied by what were known at the time as Hamathite characters. Three lines of these were inserted between the face of the god and his uplifted left arm, four lines more were engraved behind his worshipper, while below, on a level with an aqueduct which fed a mill, were yet other lines of half-obliterated hieroglyphs. It was plain that in Lykaonia also, where the old language of the country still lingered in the days of St. Paul, the Hittite system of writing had once been used. Another stone inscribed with Hittite characters had come to light at Aleppo. Like those of Hamath, it was of black basalt, and had been built into a modern wall. The characters upon it were worn by frequent attrition, the people of Aleppo believing that whoever rubbed his eyes upon it would be immediately cured of ophthalmia. More than one copy of the inscription was taken, but the difficulty of distinguishing the half-obliterated characters rendered the copies of little service, and a cast of the stone was about to be made when news arrived that the fanatics of Aleppo had destroyed it. Rather than allow its virtue to go out of it—to be stolen, as they fancied, by the Europeans—they preferred to break it in pieces. It is one of the many monuments that have perished at the very moment when their importance first became known. This, then, was the state of our knowledge in the summer of 1879. We knew that the Hittites, with whom Hebrews and Egyptians and Assyrians had once been in contact, possessed a hieroglyphic system of writing, and that this system of writing was found on monuments in Hamath, Aleppo, Carchemish, and Lykaonia. We knew, too, that in Lykaonia it accompanied figures carved out of the rock in a peculiar style of art, and represented as wearing a peculiar kind of dress. SLABS WITH HITTITE SCULPTURES. (Photographed in situ at Keller, near Aintab.) Suddenly the truth flashed upon me. This peculiar style of art, this peculiar kind of dress, was the same as that which distinguished the sculptures of Karabel, of Ghiaur-kalessi, and of Kappadokia. In all alike we had the same characteristic features, the same head-dresses and shoes, the same tunics, the same clumsy massiveness of design and characteristic attitude. The figures carved upon the rocks of Karabel and Kappadokia must be memorials of Hittite art. The clue to their origin and history was at last discovered; the birthplace of the strange art which had produced them was made manifest. A little further research made the fact doubly sure. The photographs Professor Perrot had taken of the monuments of Boghaz Keui in Kappadokia included one of an inscription in ten or eleven lines. The characters of this inscription were worn and almost illegible, but not only were they in relief, like the characters of all other Hittite inscriptions known at the time, among them two or three hieroglyphs stood out clearly, which were identical with those on the stones of Hamath and Carchemish. All that was needed to complete the verification of my discovery was to visit the Pass of Karabel, and see whether the hieroglyphs Texier and others had found there likewise belonged to the Hittite script. More than three hours did I spend in the niche wherein the figure is carved which Herodotos believed was a likeness of the Egyptian Sesostris. It was necessary to take 'squeezes' as well as copies, if I would recover the characters of the inscription and ascertain their exact forms. My joy was great at finding that they were Hittite, and that the conclusion I had arrived at in my study at home was confirmed by the monument itself. The Sesostris of Herodotos turned out to be, not the great Pharaoh who contended with the Hittites of Kadesh, but a symbol of the far-reaching power and influence of his mighty opponents. Hittite art and Hittite writing, if not the Hittite name, were proved to have been known from the banks of the Euphrates to the shores of the Ægean Sea. The stone warrior of Karabel stands in his niche in the cliff at a considerable height above the path, and the direction in which he is marching is that which would have led him to Ephesos and the Mæander. His companion lies below, the block of stone out of which the second figure has been carved having been apparently shaken by an earthquake from the rocks above. This second figure is a duplicate of the first. Both stand in the same position, both are shod with the same snow-shoes, and both are armed with spear and bow. But the second figure has suffered much from the ill-usage of man. The upper part has been purposely chipped away, and it is not many years ago since a Yuruk's tent was pitched against the block of stone out of which it is carved, the niche in which the old warrior stands conveniently serving as the fire-place of the family. No trace of inscription remains, if indeed it ever existed. At any rate, it could not have run across the breast, as Herodotos asserts. THE PSEUDO-SESOSTRIS, CARVED ON THE ROCK IN THE PASS OF KARABEL. The account, indeed, given by Herodotos of these two figures can hardly have been that of an eye-witness. Instead of being little over three feet in height, they are more than life-size, and they hold their spears not in the right but in the left hand. Their accoutrement, moreover, is as unlike that of an 'Egyptian and Ethiopian' as it well could be, while the inscription is not traced across the breast, but between the face and the arm. Nor was the Greek historian correct in saying that the pass which the two warriors seem to guard leads not only from Ephesos to Phokæa, but also from Sardes to Smyrna. It is not until the pass is cleared at its northern end that the road which runs through it—the Karabel-déré, as the Turks now call it—joins the Belkaive, or road from Sardes to Smyrna. It is evident that Herodotos must have received his account of the figures from another authority, though his identification of them with the Egyptian Sesostris is his own. Not far from Karabel another monument of Hittite art has been discovered. Hard by the town of Magnesia, on the lofty cliffs of Sipylos, a strange figure has been carved out of the rock. It represents a woman with long locks of hair streaming down her shoulders, and a jewel like a lotus-flower upon the head, who sits on a throne in a deep artificial niche. Lydian historians narrate that it was the image of the daughter of Assaon, who had sought death by casting herself down from a precipice; but Greek legend preferred to see in it the figure of 'weeping Niobe' turned to stone. Already Homer told how Niobę, when her twelve children had been slain by the gods, 'now changed to stone, broods over the woes the gods had brought, there among the rocks, in lonely mountains, even in Sipylos, where they say are the couches of the nymphs who dance on the banks of the Akheloios.' But it was only after the settlement of the Greeks in Lydia that the old monument on Mount Sipylos was held to be the image of Niobę. The limestone rock out of which it was carved dripped with moisture after rain, and as the water flowed over the face of the figure, disintegrating and disfiguring the stone as it ran, the pious Greek beheld in it the Niobę of his own mythology. The figure was originally that of the great goddess of Asia Minor, known sometimes as Atergatis or Derketo, sometimes as Kybelę, sometimes by other names. It is difficult for one who has seen the image of Nofert-ari, the favourite wife of Ramses II., seated in the niche of rock on the cliffs of Abu-simbel, not to believe that the artist who carved the image on Mount Sipylos had visited the Nile. At a little distance both have the same appearance, and a nearer examination shows that, although the Egyptian work is finer than the Lydian, it resembles it in a striking manner. We now know, however, that the 'Niobę' of Sipylos owes its origin to Hittite art. On the wall of rock out of which the niche is cut wherein the goddess sits Dr. Dennis discovered a cartouche containing Hittite characters. By tying some ladders together he and I succeeded in ascending to it, and taking paper impressions of the hieroglyphs. Among them is a character which has the meaning of 'king'8. How came these characters and these creations of Hittite art in a region so remote from that in which the Hittite kingdoms rose and flourished? How comes it that we find figures of Hittite warriors in the Pass of Karabel and on the rocks of Ghiaur-kalessi, and the image of a Hittite goddess on the cliffs of Sipylos? Whose was the hand that engraved the characters that accompany them,—characters which are the same as those which meet us on the stones of Hamath and Carchemish? We have now to learn what answers can be given to these questions.

MONUMENT OF A HITTITE KING FOUND AT CARCHEMISH.

|

|

|

|

|

6) In the Academy of Aug. 16th, 1879. 7) Travels in Syria, p. 146. 8) A copy of the inscription made from the squeeze is given in the Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archæology, VII. Pt. 3, Pl. v. An eye-copy, made from the ground by Dr. Dennis, on the occasion of his discovery of the cartouche, was published in the Proceedings of the same Society for January 1881, and is necessarily imperfect.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD