New Testament History

By Harris Franklin Rall

Part 1. The World Of The Early Church

Chapter 2

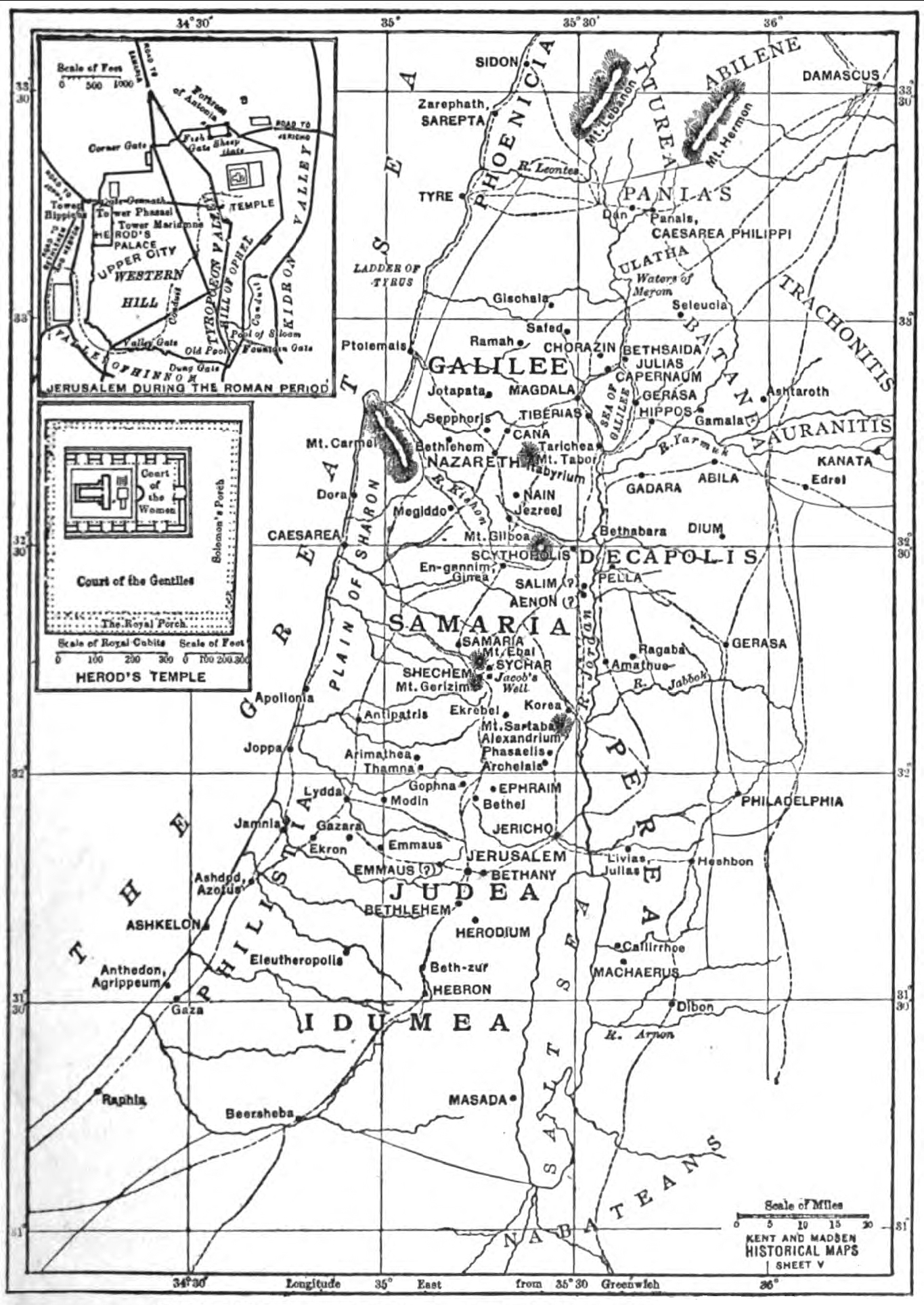

The Jewish WorldGreece and Rome and the Orient all had their influence upon Christianity and its development, but it was the Jewish world from which the new faith directly sprang. Its founder was a Jew and spoke a Semitic tongue. His work was done within the narrow borders of the little Jewish province. The early leaders of the movement, Paul, Peter, and James, were all of the same race. Above all, it was the noble faith of Israel in which Christianity footed. What was the place of the Jew in the Roman world? The Jew was, first of all, a part of a larger Semitic world. Rome's old enemies, the Carthaginians, belonged to this race, as did the Phoenicians along the east coast of the Mediterranean; and other Semitic peoples extended as far east as Babylonia. Most of these used a common tongue called Aramaic. The Jews at this time used a dialect of this tongue instead of the old Hebrew in which the Old Testament was written. Palestine was the old home of the Jews. It is usually thought of as having been shut off from the rest of the world and from the great movements of history. As a matter of fact, it lay on the great highways that joined the nations of antiquity. It was a meeting place for three continents. Along these roads swept in turn the armies of the great conquering nations, Babylonia, Assyria, Egypt, Macedonia, Syria, Rome. Israel had felt the influence of all these and yet had preserved her individuality. At the time of Jesus' birth she was ruled by Herod the Great, a selfish and cruel but strong monarch. The land had been separated by Rome, however, into several divisions. The province of Judaea was the principal one. This included Map: Palestine In the Time of Jesus Palestine In the Time of Jesus, 4 B.C.—30 A.D. (Including the Period of Herod 40-4 B.C.) Idumĉa to the south, Judĉa proper (corresponding to the old southern kingdom), and Samaria (corresponding to the old kingdom of Israel). The chief Jewish population lay in the two latter, which formed a territory but little larger than half of the State of Iowa or Illinois. North of Samaria lay Galilee, where Jesus' home was. It had not long been settled by the Jews and was still half Gentile. Across the Jordan lay Perĉa, which was joined with Galilee to form a tetrarchy. After Herod the Great the kingdom was divided. At the time of Jesus' ministry the province of Judĉa was under the direct control of the emperor. The governor appointed by him was called procurator, and at this time was Pontius Pilate. The tetrarchy of Galilee and Perĉa at the time of the Gospels was under Herod Antipas, whom Jesus called the fox. The Jews had a very large measure of self-government in Judĉa under their high priest and Sanhedrin, or Senate. For the most part their religious customs and scruples were respected. But the crushing burden of taxation was never intermitted. There were poverty and distress in abundance. The hated publican was always present as a sign of their bondage, and constantly smoldering underneath all was the religious-patriotic passion which flamed forth at last in the hopeless revolt against Rome that ended in the destruction of Jerusalem. But the Jew was not limited to Palestine then any more than he is now. in their earlier history the Jews had been carried off by force into captivity, while in the later years vastly greater numbers had gone into other lands of their own free will. The scattered Jews were called the Diaspora, or Dispersion. The Jew had once been a nomad with herds and flocks, as his Arab cousin is today. When he settled in Canaan he became an agriculturist. But before the time of Christ he had begun the career of tradesman, in which we know him so well. Then, as now, he was scattered throughout the world. Over a century before Christ the Grecian geographer Strabo wrote, "One cannot readily find any place in the world which has not received this tribe and. been taken possession of by it." There were from four to four and a half million Jews in the empire, probably not far from a twelfth of the whole population. Then, as now, they were looked down upon and often persecuted. And yet they enjoyed special privileges. They usually formed In each city a special community with some measure of self-government. The synagogue was the center of the community, and over a hundred and fifty of these are known to have been scattered throughout the empire. This dispersion of the Jews was of the greatest significance for Christianity. Rome built roads for the gospel, Greece gave it a language, but the Jews had prepared the approach to men's hearts and minds. Every Jewish synagogue was a center of religious influence. About it there was usually a fringe of converts, or proselytes, or at least a number of interested inquirers and attendants who were spoken of as "devout" or "God-fearing" (Acts 10:22; 17:4). Despite the prejudice against the Jews, the pure faith, the simple worship, and the high moral ideals must have proven attractive to many noble souls in the Roman world. Thus the leaven of the Old Testament moral and spiritual ideals was spread throughout the empire, and Paul's first and best converts were among these Gentiles that had already been touched by Judaism. The religion of Judaism is of supreme interest to the Christian. Jesus did not profess to bring a new faith. He came to the Jews with the faith of their fathers; his God was Jehovah, "the God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob." The highest expression of the Hebrew religion was in the prophets and the psalms. It was not merely the thought of one God, such as Grecian philosophy had reached; it was the character of that God as a God of righteousness and mercy. From this conception of God came the pure and noble idea of religion; for such a God asks of men not sacrifice and ritual, but "to do justly, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with God" (Mic 6:8). Upon this religion of the prophets Jesus built, and we cannot understand Christianity without it. Side by side with it in the Old Testament is a great system of ceremonial law, but with this priestly religion Jesus showed little sympathy. There is a difference, however, between the Old Testament religion and the religion of Jesus' day, or Judaism. A living religion does not stand still. The last four centuries before Christ were of great importance for the Jewish religion, though we read little of this history in the Old Testament. The Jews had become a part of Alexander's empire. The Greeks, not contented with political rule, wished to change the eastern civilization and Hellenize it. At first they made some progress with the Jews. Grecian games and customs were introduced. There was a strong and growing liberal party. Then Antiochus, called Epiphanes, tried to force the process. He tried to compel the Jews to give up circumcision, the Sabbath, and the books of the law. As a result he merely strengthened the opposition and aroused the people. The party of the law triumphed. Everything that separated the Jews from the nations was emphasized. The passion of the Jews and the chief concern of religion became more and more the mere keeping of the many precepts of the law. All this bore its fruits in Jesus' day. Religion was not fellowship with God. God was far off. In his place were these laws which he had given. Religion was keeping these laws, and the endless traditions which had grown up about them. It was an almost impossible burden, and many made no attempt at all to carry it (Acts 15:10). Side by side with the law was the hope. We might describe the Jewish religion as an ellipse with the law and the hope as the two foci about which it moved. This hope we first meet in the Old Testament. It is the hope of the Messianic kingdom, that at some time Israel's enemies are to be overthrown and she is to reign in triumph. Prophets like Isaiah give us a wonderful picture of the new earth that is to come, in which peace and righteousness shall prevail. Usually, though not always, the prophets spoke of a Messiah who was to bring in this new kingdom. Such a hope might be very broad and generous, as in Isa 19:24, 25: "In that day shall Israel be the third with Egypt and with Assyria, a blessing in the midst of the earth; for that Jehovah of hosts hath blessed them, saying, Blessed be Egypt my people, and Assyria the work of my hands, and Israel mine inheritance." But it might be very narrow as it was in Jesus' day, when the Jews dreamed only of their own triumph and thought not so much of a reign of righteousness as of material blessings. The Jews had resisted every attempt to break down their peculiar faith and to engulf them in the mixture of religions and races which made the Hellenistic-Roman world. They did not, however, remain uninfluenced. This is especially seen in the changes that took place in the Messianic hope. We see this in Jewish writings of this period. We hear about angels and demons. The world is divided into two opposing forces of light and darkness, and these are to meet at last in a great conflict which is to bring in the new age. There are to be resurrection and judgment, heaven and hell. These ideas, which are lacking in the Old Testament, show the influence of the East, and especially of Persia. We have spoken so far as though there were no differences of religious thought among the Jews. The New Testament pages show us that there were different parties and classes. First among these are the Pharisees. They were the separatists, or Puritans, of their day. In the days of the struggle against Antiochus and the Greek customs they stood for the law and the separation of Israel from all the pagan life about them. They favored the strictest observance of the law and all the rules that had been built around it by tradition. There were not many of them—Josephus says six thousand—but their influence with the people was very great. With them are usually mentioned in the New Testament the scribes. They were the teachers of the law, the lawyers, and they usually belonged to the Pharisaic party. They studied not so much the law as the mass of teachings about the law which had been handed down from the older rabbis. Their teaching was simply a remembering and repeating of these traditions, a dreary and endless process that sank more and more to trifles and puerilities, while neglecting "the weightier matters of the law, justice, and mercy, and faith." The Sadducees were the aristocrats, the party of the priestly nobility. They were conservatives in theology, disregarding the traditions of the scribes, holding only to the older written law, and refusing more modern doctrines like those of the resurrection and of spirits. In religion, however, they represented the more liberal and worldly wing. They were not so strict in observing the law and were quite ready to make alliance with the Romans if it would keep them in power. They had no influence with the people and their power depended upon their control of the temple. After the destruction of the temple and the city in the year 70 they disappear. With all their faults the Pharisees were the real representatives of the religious life of the people. But if they show the strength of Judaism, they show its weakness too. The religion of the law could not save men. With those who felt that they had kept the law, like the Pharisees, it gendered formalism and pride. With others it created either indifference or despair; the law was no help, but an impossible burden. Never did a people show more zeal for religion. "I bear them witness that they have a zeal for God," says Paul (Rom 10:2). But it could not give men peace of heart of moral victory. Judaism trained the conscience which she could not still. She stood far above the other religions of the day. She saw that salvation must mean righteousness. Jeremiah had spoken of the law that was to be written in men's hearts (31:31-34). Ezekiel had written of the new spirit that was to be given (36:26, 27). The psalmist had uttered his great petition, "Create in me a clean heart, O God; and renew a right spirit within me" (51:10). But the religion of law could not bring this about. That remained for a new faith. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD