New Testament History

By Harris Franklin Rall

Part 3. The Jerusalem Church

Chapter 24

From Jewish Sect to Christian ChurchThe most interesting question in New Testament history is, How did the Jewish sect become the Christian Church? Here at the beginning stands the little Christian community at Jerusalem. Its members are loyal Jews. They have a hope and a life which other Jews have not; but still they think of themselves as Jews, and they keep the rules of the religion of their people. They would have welcomed Gentiles that might have come to them, just as the Jews welcomed such converts. But they would have expected such converts to keep the Jewish laws of religion as they did; in other words, first to become Jews. In a brief generation the change takes place. The community at Jerusalem gives place to the church of the empire. Christianity is being preached, not as a Jewish hope, but as good news for all men. Nothing is said about being a Jew or keeping Jewish rules, but only about faith in Christ, and about living a new life of love in the Spirit of God. It is Christianity as a universal and spiritual religion. This is the greatest crisis in the life of Christianity. The change did not take place without a struggle. Two great forces were at work to bring it about. The first was the pressure of outward events, the persecutions of the Jews, which showed the disciples that the new was really different from the old. The second was the inner force of the spirit of the new religion itself. This was the main cause in the change. It was this spirit, working through men like Stephen and Barnabas and Paul, that made the new faith a world faith. The first years of the Christian community at Jerusalem were, on the whole, a period of peace. Luke reports only two cases of persecution. The first instance occurred in connection with the healing of a lame man at the temple by Peter and John. Attracted by the event, the people gathered together and were addressed by the apostles, who called them in the name of Jesus to repent and look forward to the coming of Jesus as Messiah to restore all things. Upon this the temple guards arrested them for making a disturbance and the next day they were brought before the Sanhedrin. It is not the Pharisees, the old foes of Jesus, that are proceeding against the disciples here, but the Sadducees. Worldly and at heart religiously indifferent, the Sadducees probably cared very little about the disciples preaching the resurrection. They did fear the results that might come from the development of such a movement, to which they thought they had put an end with the death of Jesus (Acts 3:1-26). Despite the warning given the apostles, the movement continued to grow. A second time the Sadducees, or temple party, laid hold upon the leaders and put them in jail. At this juncture, Luke tells us, it was the counsel of Gamaliel that saved them: "Refrain from these men, and let them alone: for if this counsel or this work be of men, it will be overthrown: but if it is of God, ye will not be able to overthrow them; lest haply ye be found even to be fighting against God." Gamaliel was a rabbi of highest standing, and his advice was followed (Acts 5:12-42). These cases, after all, were but incidents. The Christian community had relative peace and so a good opportunity for that rapid growth of which Luke speaks. The Sadducees came to look upon them as harmless enthusiasts, or else were deterred from action against them by their growing favor with the people. The Pharisees, who had been so bitter against Jesus, showed no hostility. The reason for this is not far to seek. These disciples offered no criticisms, but kept the law as good Jews, went to the temple, and observed hours of prayer and rules of purity. But a change was taking place within the church itself. Among the many new members that came to it were included Greek-speaking Jews, or Hellenists. We hear of them in connection with the appointment of the seven. They were newer members of the community and their widows were being neglected in the distribution of relief. A majority of the seven then appointed were probably Hellenists, and Stephen is usually reckoned with them. These Hellenists were Jews who had lived abroad but had returned to Jerusalem. This return indicated their devotion to their country and its faith. At the same time their life in other lands and their use of the Greek tongue would tend to make them more open-minded. Among these men we can reckon probably Philip, who carried the gospel to Samaria; Barnabas, whose name is put before that of Paul in the account of the first mission across the sea; and Stephen, the first martyr. It was Stephen who brought on the crisis. What he taught we cannot definitely know. We have only the accusations of his enemies and Luke's report of his speech, which at best is fragmentary, being broken off at the point where he was beginning to set forth his own position. Stephen did not anticipate Paul's teaching. He did not oppose the law by saying that men were saved by grace alone through faith, and not by keeping the law. He spoke of the law as "living oracles." But he aroused their enmity at two points, (1) The temple, he declared, was only temporary and not really necessary. God did not dwell in houses made with hands. Probably Stephen went back here to the word of Jesus about the destruction of the temple. Now, as then, it aroused their fury. The temple and its inviolability were at the heart of their faith. Jeremiah had made such an attack once and suffered for it (Jer 7:1-15; 26:8, 9). At this point perhaps his opponents interrupted him with fierce accusations: He was speaking against the holy place and against the law. Stephen may well have had Jeremiah in mind when he answered, and still further stirred their hostility. (2) "You charge me with opposing the law. It is you that oppose it. You are like your fathers, always resisting God when he spoke through the prophets, receiving the law but never keeping it" (Acts 6:8 to 7:53). This last charge also reminds us of Jesus' teaching in his attack upon the Pharisees and in the higher righteousness which he demanded. Both these points are reflected in the charges which they preferred when they brought him before the council: "This man ceaseth not to speak words against this holy place, and the law: for we have heard him say, that this Jesus of Nazareth shall destroy this place, and shall change the customs which Moses delivered unto us" (Acts 6:13, 14). The attack upon the temple had stirred the Sadducees; what he had said about the law aroused the Pharisees. The trial had been before a formal session of the council. Now, apparently, the session broke up in confusion. To their minds he had himself confirmed the charge of blasphemy made against him. Whether with Roman consent or not, we do not know, but they hurried him forth and inflicted the penalty provided by their law, death by stoning. Luke shows us the spirit of this first disciple who sealed his witness with his death: "And they stoned Stephen, calling upon the Lord, and saying, Lord Jesus, receive my spirit. And he kneeled down, and cried with a loud voice, Lord, lay not this sin to their charge" (Acts 7:54-60). Stephen wrought more by his death than by his teaching in life. He brought to a close the day when Christianity could live on undisturbed as a harmless Jewish sect. In their formal charges the witnesses may have been false, as Luke suggests. In the main point they were right: this new movement meant an end to the temple and to the customs of Moses. What was more important, Stephen helped not merely their enemies but the church herself to see the meaning of the faith. In the first place came the fact of persecution. It did not matter that most of the disciples had not shared in the insight of Stephen or held his views. They found themselves driven forth on account of the temple and the law, though they reverenced both. They had to face the question: What is our real faith, Jesus the Messiah and the hope of his coming, or Moses and the temple and the laws? And they saw how clearly Christ and the hope of the Kingdom and the new fellowship stood first, and how much they meant. In the second place, Stephen initiated the first missionary period. True, there was no such clear purpose in their minds as when Paul set forth. But an ardent living faith drives to utterance. "They therefore that were scattered abroad went about preaching the word" (Acts 8:1-4). The period of persecution and expansion thus went hand in hand. The driving force back of the persecution was the Pharisees, and the leader in the movement was a young man named Saul, who had been present at the stoning of Stephen. The apostles apparently remained in Jerusalem in hiding. Many of the disciples scattered throughout Judęa and Galilee and Samaria, some probably going farther. There must have been little groups of disciples beyond these limits even before this time; we read of disciples at Joppa, Lydda, Cęsarea, Damascus, and Antioch. The real work of expansion did not come through formally appointed missionaries or through the apostles. For the most part, it was done by common men and women, speaking as they had opportunity to those whom they met in their ordinary work of life. It was a great lay movement, and such, indeed, Christianity remained for the first century. A few figures, however, stand forth. The first is Philip, not one of the twelve but one of the seven, for the twelve were in Jerusalem. His first mission was to Samaria, his next southward as far as Gaza (Acts 8:5-40). Only two incidents are given from these journeys. Near Gaza Philip met an Ethiopian, a man of high official position at home, and a proselyte, who was just returning from Jerusalem. The reference to Isaiah shows us how the early Christians were already interpreting the Old Testament in relation to Christ. The story of Simon Magus gives us a side-light upon conditions at that time. It was a day of many religions and much superstition throughout the empire. There were all manner of priests and prophets and charlatans, and people were ready to believe almost any magic or mystery. Simon was but one of many who fed on this spirit, which was for him a source of livelihood. In Philip he recognized a superior power, and even more so in Peter and John when these came down from Jerusalem. To be able to give the Holy Spirit by the laying on of hands seemed to him just another profitable device, and he was willing to pay well for the secret. All this was not so much a sign of great wickedness as a picture of what religion meant to many in that day—not faith and righteousness, but magical rites and mysteries of all kinds. Similar cases are met later in Paul's work: Elymas, the sorcerer, and the soothsaying girl (Acts 13:6; 16:16). The question of Peter's relation to this expansion must be considered later on. Luke shows us clearly that this new movement in the church was a lay movement. The spread of the gospel was not through appointed ministers and missionaries, but simply through those "that were scattered abroad." These went as far as Phoenicia and the coast near by, the great city of Antioch to the north, and the island of Cyprus. Of all this work we have but one definite item. At Antioch these disciples preached not only to Jews but to Gentiles also. Their success here was so great, and their preaching to the Gentiles such an innovation, that the church at Jerusalem had to take notice of it. Fortunately, it was Barnabas whom they sent down, himself a Hellenist from the island of Cyprus that lay off this coast. "He was a good man, and full of the Holy Spirit and of faith." Even greater success followed his coming until the burden and the opportunity drove him to look for aid. And so he took a step which helps to usher in another period. "He went forth to Tarsus to seek for Saul; and when he had found him, he brought him unto Antioch. And it came to pass, that even for a whole year they were together with the church, and taught much people; and that the disciples were called Christians first in Antioch" (Acts 11:19-26). Directions for Reading and Study

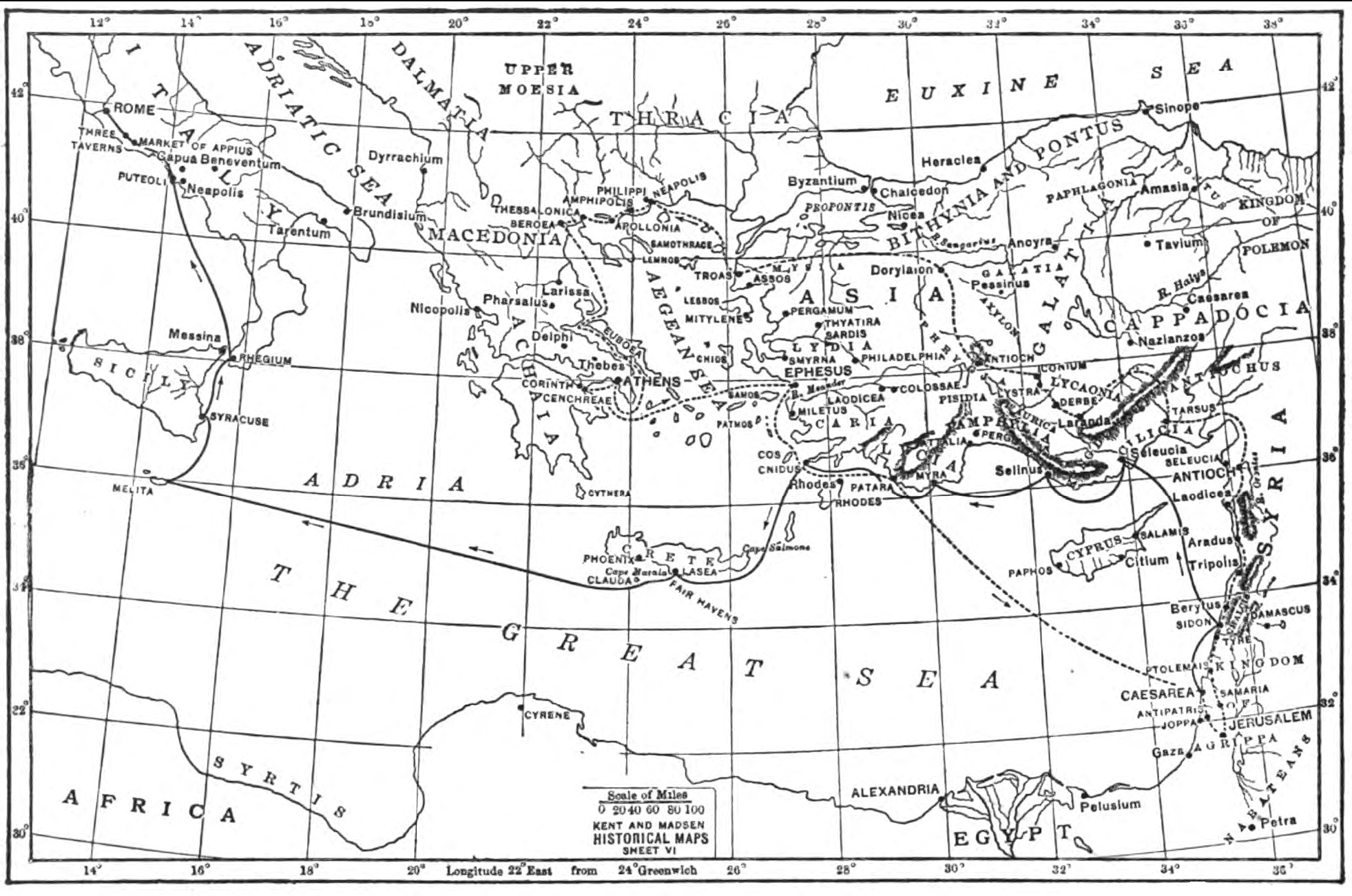

St. Paul's Journeys and the Early Christian Church, 40-100 A.D. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD